Here’s a helpful article from surveyor John Champion on how to get, store and use one of our most precious resources while cruising—water…

Water is useful stuff. We like to drink it, wash with it and clean things with it—pretty much in that order. And the abundant liquid we float on is second best for these purposes. The days of crossing an ocean with a couple of jerry cans and gloating over the moisture in a fishes eye seem to be long gone. In place of frugality we now want, and in some instances insist upon, a virtually boundless supply of fresh water.

Boats with pressure water systems are pretty much standard and it is surprising how many now pack washing machines and even dishwashers aboard. This is all well and good, but such devices have a thirst and to be of any use outside a marina, this thirst must be satisfied. We must have water, and lots of it.

TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS

The easiest (relative term) and most expensive way to do this is to cough up the money for a big watermaker, spend an eternity, or another fortune, installing it, then troubleshoot and learn how to operate and maintain it correctly. Failure to do this properly will quickly reduce the wonder of technology to a useless pile of pumps and hoses until the next competent and available dealer or service agent is encountered. Notice the key words here? Competent and available. In my experience this doesn’t happen very often, but I did hear of an astrologer in Turkey who was pretty good at predicting such events; so read the manual and learn how to do it yourself.

Essentially, a high output watermaker turns diesel or gas into water. (Damn fool, you say, it turns seawater into fresh by removing the salt! That’s why it is called a desalinator!) Yes, but the machine requires energy and the bigger the output, and hence usefulness, the more energy is required. Small DC units certainly can be run in good energy producing conditions by solar and wind depending on the other electrical demands aboard. Much above the 15 liters per hour mark and power consumption gets right up there. Add a DC fridge, freezer and a powerful autopilot—and who knows what else—and the solar panels will have to be heroic to keep up. Plus, you will still suck the batteries dry at night or on overcast days.

CHOOSE CAREFULLY

There are three common options for powering a watermaker, not including tow behind models. Perhaps most popular is DC battery powered, 12 or 24 volts according to your vessel’s system, AC electricity or engine driven. Each has pros and cons. Small to medium DC units can be run to some extent off the batteries without an engine, how often and how long will depend on your charging and storage system. If you have a first rate, efficient DC system with significant alternate charging capacity, then you’re in business. More likely you will struggle to keep the batteries adequately charged and not fall below the 50% discharge mark, which will shorten their already short and expensive life. Under these circumstances you will start the engine in order to make water when required; in essence, diesel is being turned into H2O.

Quite small units, up to perhaps five liters per hour, can even be hand operated. You could probably sweat five liters in the hour mind you. The second option is an AC powered unit. These can have serious production ability so may not be required to run for very long to meet your needs. You will, however, need to have AC power and this means a generator will have to be running unless you are in the marina with shore power. Smart people do not make water in marinas, though, as fuel and contaminants may bugger up the very costly membranes inside, but many do anyway. Running an AC watermaker via an enormous inverter may be possible under certain circumstances, while motoring for example, but is probably not a good systematic solution. If your vessel has a generator you use for air conditioning or such and has extra capacity for a watermaker, then this is a reasonable solution.

A third option is to have an engine-powered unit. This is definitely turning diesel into water, but if you are using the engine to travel you probably have spare horsepower that can be put to work. A large DC unit may be operated in this way also, as the alternator (high output, marine rated with smart regulator right?) will be putting back what the desalinator takes immediately. One little issue with watermakers is correct sizing, bigger is not always better, as in the tropics they will need to be pickled (treated with storage biocide) after three days or so without use. If left much longer than this, perhaps a week in temperate climates, nasty stuff grows in the membrane and you’re up for a ruinous bill and have no water. Some people prefer to run a smaller unit more frequently and so avoid the required pickling. Numerous models also offer an automated fresh water flush to keep the membrane fresh but this relies on using water produced by the machine as chlorine and other additives will knock the membrane on the head as well.

As you may have gathered, membranes are sensitive little fellows and if one of your mates sticks the dock hose into the wrong tank, it may be his last trip on your boat. Various filters can help protect against this. So watermakers like to be used or pickled, take your choice. Some brands use different chemicals to achieve the pickled state and these may not always be compatible between brands. What is right for one unit may well destroy another, so point this out next time you hear “Yoo Hoo, can I borrow a cup of biocide please dear?”

AWNINGS

These desirable inventions are pretty common on boats for the shade factor and with a little bit of thought can largely solve your water issues. This of course means it has to rain, which is not generally a problem in the tropics but might be in other places. Still, once set up to catch water you will always have that option if it does rain. Large awnings used at anchor will produce the best results—naturally, the bigger the catchment area, the more water.

Biminis can also be configured to catch rainwater. In any awning, a cheap nylon thru hull can be placed in what you believe to be the lowest point and a tube run from there to the tank deck fill; easy once you really have found the true low point. A well reinforced webbing loop around the underside of the thru hull fitting will allow some adjustment of the awning to keep it low. Given a good breeze, however, with the awning moving around a bit the catchment point can become isolated and pools can form, water then collects undrained and the whole lid could come down.

Permanently mounted solar panels also catch a lot of water and if there is a favored run off point then a bucket hung beneath this point—with the thru hull and hose exiting the bottom of the bucket—will catch a surprising amount in a good downpour. This is probably the most cost effective water catcher ever.

DECK CATCH

Some people have noticed how much water runs off the deck in the rain and have devised ways of catching this. At least one boat I know of (a Martzcraft 46) had a system designed into the vessel to achieve this. It would be possible to retrofit such a system into certain models of boats that employ a solid toe rail for example. These small bulwarks around the outside of the deck mean there is usually a deck drain overboard, generally a little aft of amidships, that was picked as the lowest point under sail.

Some of the drains are solid glass but some have hose that you could try and tee into to catch rain right off the deck. If memory serves me correct the Beneteau 50, Catalina 400 and I imagine many others, are suitable for this method. Some kind of three-way valve would be needed to direct the seawater overboard and the fresh water to the tank when suitable, but clean decks are certainly required and you would regret forgetting to change this one back before sailing. If your boat has perforated toe rails then keep thinking of alternatives.

TANKS

So you intend to catch or make a heap of water and it has to go somewhere. Your boat will come with a water tank or tanks—the more the merrier as it is a real bummer if the single tank leaks or is contaminated—and these tanks can vary widely in capacity, construction and security. A good tank will be robust, corrosion proof, very well secured, probably baffled to prevent water battering at the walls and will have an inspection port that allows you to clean it occasionally. Good luck with all this.

TANK CONSTRUCTION

All materials have good and bad points. Metal is strong, but can rust and welds fail. Integral fiberglass tanks have been known to suffer from osmosis on the inside and molded plastic tanks have the least inherent strength. Whatever the tank material (unless integral) the tank must be very securely fastened; many are the tales of production boat tanks breaking free in exciting conditions. Imagine getting hammered at sea and all of a sudden 400 or so liters of fresh—although this would not be immediately known, thereby adding to the thrill—water pours into the boat; this might be distressing, I think I would find it so anyway. So check those tie-down straps if you have them and see if a couple more by way of back up could be installed.

Integral tanks have the additional benefit of keeping the sea out. If the hull is breached in the tank area you will of course lose all the fresh water, but that inside wall will keep the sea out for a while at least. All tanks will require a water in fill—which is best fitted on deck as proved by a lot of older French boats whose deck fills all failed and had to be filled from inside—a water out connection for the pump and a vent. Having no, or an inadequate vent, and the tank will be continually deformed as water is pumped out and fail sooner rather than later.

Bladders are the last resort of the damned. If you are chronically short on tankage and have no accessible space to mount a solid tank then you may consider this option. They are available in all kinds of weird shapes to fit in equally weird places, but can tear, puncture, flop around and they can leak.

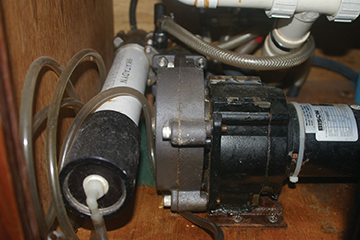

PUMPS

These are the item that will get the water from the tank to the parched or dirty individual who requires it. Pressure water is standard on all but the humblest vessel these days and the system may or may not have an accumulator tank installed. These are essentially little reservoirs that are pressurized—when full and the tap is opened the water flows without the pump running for a short while. It evens out the water pressure, can mean a little less pump work, removes the “hammering” vibrations sometimes associated with marine pressure water systems and it can fail.

Failure may simply mean it has lost the internal pressure that makes it work, which can usually be corrected with a bicycle pump, as there will be a tire type valve somewhere on the unit. Or it could rust out, break a connection or any of another million things and cause you to loose the connected tank’s water. They are generally reliable little units, however, if you have not seen yours for a few years it might be worth a look, then drink, wash and clean, in that order, in peace.

John Champion has lived aboard since 1999 and sailed half way around the world in the process. He currently floats around in Langkawi, Malaysia and offers appraisals and surveys for production boats in the region. If you are thinking of buying over that way he can be contacted at, jwchampion@live.com.au.