Thanks to Capt. John of skippertips.com for this navigation tip.

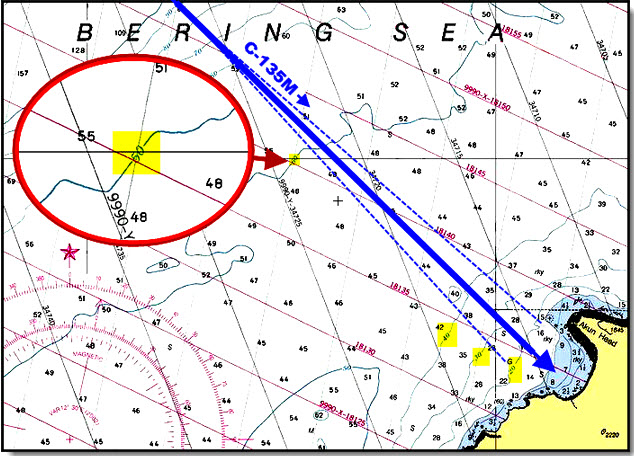

On this coastal approach chart to the Krenitzin Islands in Alaska, soundings are in fathoms. Depth curves are staggered at 10 fathom intervals. Note the 50 fathom curve about 5 miles offshore. Closer inshore, you see the 40, 30, and 20 fathom curves. The thick blue line represents the sailing course of 135° Magnetic. The light dashed blue lines show what would happen if navigational error (see below) caused our sailboat to be off a few degrees to one side or the other. Your depth sounder would still warn you that you had crossed one of the fathom curves. Use navigational techniques like this for sailing safety.

Assume that your sailing navigation will be in error. Small vessels have unstable platforms. Heeling, pitching, rolling, yawing. All of these motions cause a small vessel to wander back and forth across her intended course. Consider that navigation errors can include leeway, current, steering, compass deviation, and the “fatigue factor”.

Leeway Error

Expect your vessel to experience leeway–or “side-slip”–in a downwind direction. The amount of leeway depends on hull and keel design, vessel displacement, and point of sail. Sailboats experience more leeway when beating, close- or beam-reaching and minimum leeway when broad-reaching or running. Make your best estimate of leeway, and apply it to the course line in an upwind direction.

Current Error

Currents can push a vessel to the right or left of track (current from the side), or increase speed (current from astern) or reduce speed (current from ahead). Even with careful planning, currents along the coast or offshore can change direction and strength as wind and sea conditions change. Check current tables and marine forecasts along with local knowledge for best estimates of tidal, coastal, or ocean currents.

Steering Error

Steering a small boat in a seaway can be quite difficult. Legendary sailor John Mellor once remarked that a person steering a small sailboat would do well to keep within 5° to 10° of the course. Even with careful tracks drawn onto the nautical chart or routes plotted onto a chart plotter, your sailing vessel will often make a snake-like track above and below an intended trackline. Rotate the helm at more frequent intervals in rougher weather.

Compass Deviation Error

Even the best adjusted compass can accumulate error from unexpected magnetic or electrical influences (called “deviation”). That’s a good reason to spend the money to hire a pro compass adjuster before you leave on a cruise or voyage, or learn to do this yourself. Caution the crew to leave cell phones and computers below or well away from the compass. Twist wires nearby to help cancel out electrical influences.

“Fatigue Factor” Error

Add in the factor of crew fatigue. On a small boat, you grab, squat, kneel, go up and down companionway ladders, hang on when heeling, pull yourself up from a sitting position. Multi-tasking becomes a natural element in sailing. And it’s tiring. Fatigue leads to errors; in more than one case it has lead to disaster. Plan on being fatigued. Rest when you can, but plan on a bit of “fuzzy headedness” from time to time. Just another good reason to lessen the length of watches in thick weather.

How to Use Magic Depth Contours

Back up your black box navigation with the magic of depth curves (also called depth contours). These provide the short-handed navigator with a good safety factor for the errors described earlier. Look on your nautical chart for lines or non-concentric circles near the coast. Depth curves show equal depths all along the line or circle. Scan along the line and look for a number that indicates the depth of the curve.

First, check the margins or title block of your chart to determine whether the soundings shown are in feet, fathoms, or meters. Also note the datum for those soundings. On US charts, the usual datum will be Mean Lower Low Water (MLLW); British Admiralty charts often use a slightly more conservative datum called Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT). In all cases, never assume when it comes to soundings. Check your chart before you navigate!

Depth curves are often staggered in increments of 6 or 10. In inland or coastal waters, you will see depth curves numbered 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30. Further offshore, depth curves might be labeled 10, 20, 30, and so forth. Set your depth sounder alarm to warn you when you arrive at the outermost depth curve near a hazardous coastline.

Realize that this will be approximate; high waves could alter this reading, so take an average over a period of time. Calculate the tide (in particular for close coastal or inland waters) for your time of arrival and apply this correction to the reading displayed on your depth sounder.

Note in the illustration how the offshore 50 fathom depth curve warns you of your approach to this Alaskan Island. Further inshore, depth curves continue at 10-fathom intervals of 40, 30, and 20 fathoms.

In this case, it would be prudent to set your depth sounder to alarm when you arrive at the 50 fathom curve. That curve lies about 5 nautical miles offshore. You could also set an alarm for the remaining depth curves closer to the coast. But do not rely just on an alarm for warning (they can fail to sound). Alert the crew on watch to log the depth readings at frequent intervals each hour. Once the boat crosses the 50 fathom depth curve, the person on watch can alert the other crew in order to prepare for the final approach.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Use these sailing navigation tips to find vital depth curves to keep your small sailboat in safe water. Backup your black box navigation with valuable sailing tips like these to keep your crew safe and sound–wherever in the world you choose to cruise.