Here are some more great navigation tips from our friend Capt. John from skippertips.com…

Imagine sailing along the coast with your sailing partner and you want to “pull off the road” for some much needed rest. You open your nautical chart or electronic display to the entrances into sheltered water. Three channels lie within a day’s sail. But just one of those channels will provide you and your sailing crew with an all-weather, day or night entrance. Follow these five sailing navigation tips to help you make the best decision for sailing safety.

What five factors would you look for before you negotiated an unfamiliar inlet? Here are my thoughts; there are many more, but these would top my personal “cruise plan” list for safe sailing navigation.

1. Make Dredged Channels Your #1 Top Priority.

Look for two dashed lines that mark the edges of a channel. This chart symbol indicates an improved, dredged channel. It will be maintained to the specific depths indicated in the chart notes to prevent silting from nearby wave or breaker action.

2. Find Well Marked, Lighted Aids to Navigation.

Channel edges should have government maintained buoys or light structures to mark the edge of the shoal. These aids should be charted. Beware of any inlet that lacks charted aids to navigation or shows the inlet marked by private aids. Private aids (marked “Priv” or “priv” on the chart) may or may not be maintained by their public owners. On the other hand, government maintained aids have specific preventative maintenance service schedules for inspection, repair or overhaul.

3. Look for These Chart Note “Red Flags”.

Inlet notes are automatic “red flags”. Unless you have a high degree of local knowledge and experience, consider any chart note that warns of a dangerous inlet as an automatic notice that you should “go around”. Find an alternate route if possible. Inlet notes warn that buoys are not charted and often advise not to use the inlet without local knowledge. Never place a lot of trust on any uncharted buoy inside an unimproved inlet; they can drag off station after heavy weather or storms.

4. Use Channel Ranges (Transits) for Backup.

Look for charted channel ranges or natural ranges to help you maintain the channel center. Water will be deepest here. Ranges serve a secondary purpose to help you navigate if charted buoys or lights are missing, have been relocated or are extinguished. These discrepancies will be in the local notice to mariners or notices to mariners, but you may have missed them.

5. Wait for “Flood Begins” to Make Your Entry.

Combine an ebb current with an onshore breeze and you can bet a sea will build. Consider that water inside even a dredged inlet can be quite shallow. On the ebb cycle, current flows out to sea. A stiff breeze that blows against current can create breakers in shallows. Slow sailboats can have a tough time sailing against an ebb.

Time your arrival for the slack just before a flood cycle begins. The onshore breeze and flood will then be in harmony. This should help calm the seas and you’ll get an extra push once the flood begins.

Which Inlet Would You Choose?

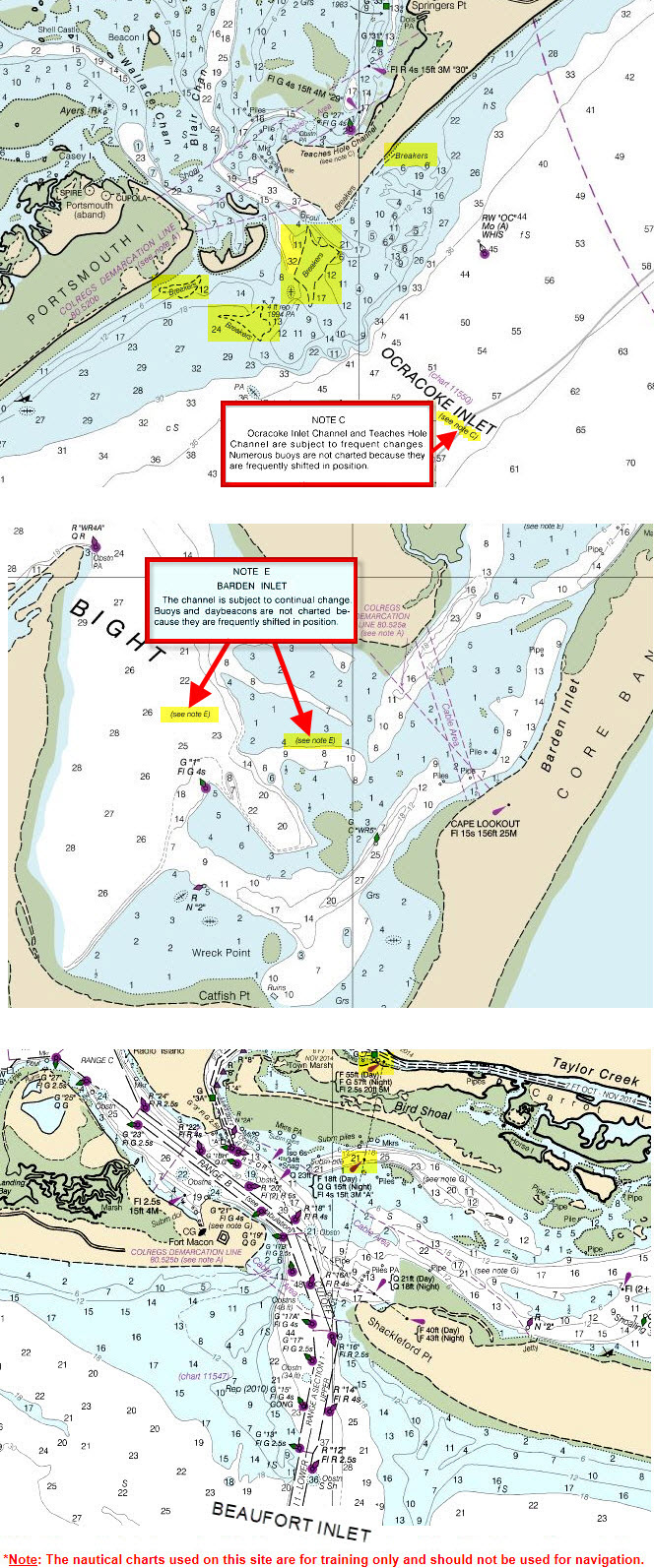

Here are three inlets located within a 40 mile span of coastline; less than half a day sail. Look over the choices. Determine the difficulty of entry, proximity of shoals, possibility of shifting seabed material in wind, wave or swell (i.e. sand shifts downwind to build new bars), and the presence of dredged vs. non-dredged channels. Which one might meet most of the criteria outlined by the five factors above. Which one would you feel more confident as an all-weather, day or night point of entry? Use this same decision making process in sheltered waters.

Navigator’s Points to Ponder

Ocracoke Inlet shows breakers across the entrance. Nasty indeed unless you have intimate local knowledge. Don’t count on buoys inside a non-dredged inlet to be on station (position). Or they may be missing altogether! Strong current can pull an inlet buoy underwater. Or, she may break loose from her mooring in heavy waves and float out to sea. Buoy response teams are busy as bees and have large geographical areas to maintain. They tend to shifting bars in inlets when weather and time permit.

The middle chart section of Cape Lookout looks doable, but it may be difficult to negotiate once around the point. The cartographers warn the mariner twice about dangerous Barden Inlet to the east. Part of the channel has been marked with buoys, but note the lack of dashed lines (these would signify a dredged, maintained channel). Consider that the deeper parts of the channel could fill in after heavy weather or storm surge.

Beaufort Inlet looks good. Right off the bat, you note the dredge channel (dashed lines on each side of the channel) with a leading transit (also called a “range”) to make entrance easy day or night. Lighted buoys dominate the channels that lead into sheltered water. Even if you had to sail a bit farther to make Beaufort Inlet, it would offer you the safest entry to avoid oncoming weather, drop off an ill crew member or to find a facility for repairs or provisions.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Use these sailing tips to help you make the best “go-no-go” decision before you enter or exit an inlet. Keep your small sailboat and sailing crew or partner safe and sound–wherever in the world you choose to sail or cruise!