Hurricanes aren’t as entertaining in real life as they may appear on TV (published September 2013)

The warm September morning started out peacefully enough. As dawn approached, seawater was lapping up over the normally-dry parts of the low lying coastal land. Later in the morning, as everyone went on about their normal chores, children played in the slowly rising, almost pond-like water. The local chief meteorologist began to observe the steep drop in the barometer and he realized that problems were brewing. He began to raise an alarm. Few paid much attention. Within 24 hours, 6,000 people would die, and pictures of the city’s aftermath now look more reminiscent of Hiroshima after its atomic blast in 1945 than of any other city following a storm. That was the scene in Galveston, Texas on September 9th and 10th, 1900.

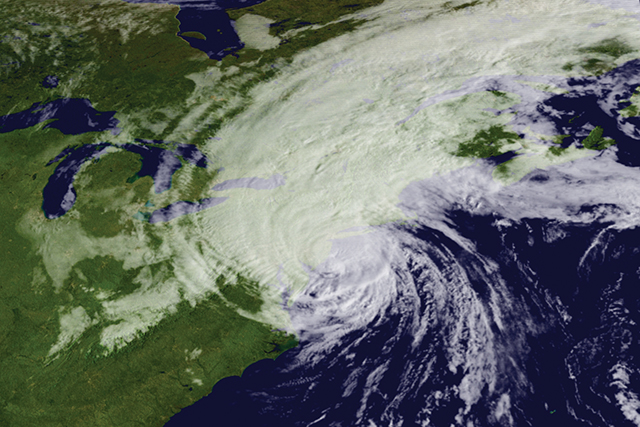

Whether on shore or offshore, hurricanes are not to be taken lightly. It’s true enough that our weather forecasting techniques have improved significantly over the past 113 years, and communications enable us to spread the word far and wide. People are more aware of the importance of taking precautions, especially following more recent events such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. That said, an above average probability is forecast for major hurricanes along the US coast for the 2013 hurricane season.

Putting hurricane realities into perspective, it should be mentioned that the weakest level of a hurricane has 74 to 95 mph winds. The strongest is in excess of 157 mph.

In 95 mph winds, the wind strength prevents people from walking upright. Who would want to? With lawn furniture and BBQ grills flying through the air on shore, the upright person would present a larger target for a multitude of lethal missiles unleashed by the wind! Offshore, a person trying to walk upright could easily be blown overboard. A stunning fact, however, is that in many places, it is the water that accompanies a hurricane that creates the most devastation.

HOW HURRICANES FORM

All weather is complex with a wide range of variables. Tropical low pressure systems, as an example, are quite different from extra-tropical lows—lows that are predominant in areas outside of the tropics. Hurricanes often start out as tropical waves, becoming tropical depressions, lows, and storms if conditions are suitable for development. A variety of criteria must be met in order to progress from tropical storm to hurricane strength.

During the initial stages of a tropical low pressure system, there will be a disturbed area with clusters of thunderstorms. In the Atlantic, as an example, the clusters could be along a tropical wave that originates in northwest Africa or along an old cold front that can occur anywhere from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to the Bahamas into the Gulf of Mexico. As the tropical wave develops into a tropical depression, the thunderstorms organize and an area of surface low pressure forms. The thunderstorms converge towards the center of lower pressure.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the thunderstorms spiral counter-clockwise, while in the Southern Hemisphere the thunderstorms spiral clockwise. When sustained winds are less than 35 mph, the tropical low is classified as a tropical depression.

In order for the tropical depression to continue to develop and become a tropical storm, the inflow of thunderstorms and warm humid air must increase. The pressure continues to fall, and sustained wind speeds must exceed 35 mph. At that point, in the North Atlantic, a tropical storm is named.

With clouds and warm, humid air inflows continuing to build, the center barometric pressure continues to drop. An “eye” is likely to form at the center of the low pressure system. In order to continue storm development into hurricane strength, sea temperatures need to be at least 81 degrees. Tropical systems become classified as hurricanes when sustained winds reach 74 mph.

Warm water provides the energy that fuels the convective system. The warmer the water, the more energy is available for hurricane strength to develop. The moist air and clouds in the vicinity of the system allow for efficient transmission of that energy. And the lack of wind shear aloft, allows the convective system to develop fully, reaching higher altitudes and colder temperatures.

Because there are various elements that go into building the strength of a tropical depression, storm or hurricane, if any of these critical elements are removed, the systems can lose some or all of their strength. As a hurricane moves over land, as an example, it loses its primary source of energy—the warm ocean. Additionally, the increased friction over the surface of land slows the inflow of energy into the convective system. Dry air is introduced, instead of the more moist air of the ocean, so fewer clouds are created. And strong wind shear aloft from wind currents such as the jet stream will tear apart the storm’s vertical structures.

Although tropical storms have been recorded in the North Atlantic in every month of the year, the primary months for tropicals are during the late summer. That is when the water is the warmest and wind shear at its minimum.

ATLANTIC STORM TRACKS

Where hurricanes tend to form in the North Atlantic and how they tend to track vary somewhat with the month. These are general trends, however, and each tropical storm will take on its own characteristics of development and track.

June: Considered early in the North Atlantic hurricane season, June tropical storms and hurricanes frequently form in the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico. Their tracks generally take them into the Gulf States or across Florida and up the North American East Coast as they recurve towards Europe.

July: Still somewhat early for the North Atlantic hurricane season, July tropical storms more frequently begin their formation a bit further to the east than the June storms. Tracks often take the tropicals into the Gulf States or northerly along the North American East Coast before they recurve toward Europe.

August: With the peak of hurricane season approaching and the water temperatures of the tropical North Atlantic continuing to rise, August tropical storms and hurricanes form further to the east in the open Atlantic where they have more time to recurve back toward Europe without making landfall in North America.

September: This is the peak month for hurricane formation in the North Atlantic. Water temperatures are among the warmest of the year, there is relatively little upper level wind shear compared to other times of the year and clouds are plentiful. The hurricanes often begin as tropical waves undulating their way off the northwestern coast of Africa. Formation can take place as far east as 30 degrees W. latitude, giving the tropicals a great deal of distance to develop and begin a recurve toward Europe prior to reaching the islands of the Caribbean or the North American continent.

October: As the tropical North Atlantic begins to cool, hurricanes and tropical storms tend to again form somewhat further to the west and often in the southern Caribbean. These are not less dangerous or potentially less destructive storms but their main areas of formation and frequency are changing.

November: Early November is often considered the end of hurricane season. Offshore, vessels and captains departing the North Atlantic bound for the Caribbean often feel that the danger of tropicals or hurricanes is past. It isn’t. Remember that the only month in recorded history that doesn’t have a hurricane in the North Atlantic is April – and that month has had a tropical storm recorded as recently as 2003!

With North Atlantic water temperatures continuing to drop in November, storm formation occurs more often in the Caribbean. Late season hurricanes tend to have somewhat erratic paths. For example, 15 years ago the hurricane that formed near Jamaica and went “backwards” into the trade winds, going over the British Virgin Islands, St. Marten and Antigua from the west towards the east, was a late season hurricane. The tracks of these late season storms are difficult to forecast so your planning should take that into account.

FORECASTING

Weather forecasting became significantly more accurate in the mid-to-late1990’s with the increased availability of remotely sensed weather data combined with increasingly accurate weather forecast computer models. Satellites now circle the globe, providing relatively accurate wind speeds and directions and other observations in near-real-time. Due to the fact that the data is observed and re-sent via Low Earth Orbiting (LEO) polar satellites, the data-swaths have periodic gaps that are captured on subsequent orbital passes. Utilizing a number of models and a wide variety of data resources, the National Weather Service’s National Hurricane Center provides a good baseline of current hurricane information.

Weather forecasting became significantly more accurate in the mid-to-late1990’s with the increased availability of remotely sensed weather data combined with increasingly accurate weather forecast computer models. Satellites now circle the globe, providing relatively accurate wind speeds and directions and other observations in near-real-time. Due to the fact that the data is observed and re-sent via Low Earth Orbiting (LEO) polar satellites, the data-swaths have periodic gaps that are captured on subsequent orbital passes. Utilizing a number of models and a wide variety of data resources, the National Weather Service’s National Hurricane Center provides a good baseline of current hurricane information.

Weather forecast models have become increasingly accurate. However, they are far from perfect. Still the best sources of information are provided by a man-machine-mix, combining the vast data crunching and analytical capabilities of super computers with the critical, subjective perspective of trained and experienced meteorologists.

There is a wide range of computer-generated weather models from which to choose and comparing off-the-shelf models with each other, you can quickly see vast discrepancies. Far better accuracy is generally achieved in the near term when a trained meteorologist “adjusts” the modeling results tempered by experience. The NWS’ Ocean Prediction Center provides these man-machine analyses and forecasts for the North Atlantic and North Pacific.

You should be aware that GRIB files tend to smooth the data and often under-estimate wind speeds. I’ve seen GRIB files indicate maximum wind speeds in a particular hurricane estimated to be 45 knots while relevant buoy reports indicated 120 knot sustained wind speeds. So, be advised that GRIB files will not provide accurate wind speeds for an approaching tropical storm.

Contrary to what the press will have us believe, most hurricanes are relatively small weather systems. The potentially destructive areas of a hurricane seldom measure more than 400 miles across. Given enough warning and reasonable mobility, vessels offshore can often sail around them, if they go the right way and if the predicted storm track is accurate. While offshore, I’ve seen hurricanes form right overhead. I’ve watched them pass by several hundred miles away and I’ve had one pass directly over the top of me—fortunately, from the cozy confines of home. Do yourself a favor: remain aware of the weather and avoid hurricanes entirely. They’re wicked bad news when you’re caught inside their grip.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net.

HURRICANE INFO ONLINE

If you want to drill down beneath the surface of commercial weather forecasting to see the data they are using in more detail, there are three good sources online. The European ASCAT data collected from Low Earth Orbit satellites can be accessed at http://manati.star.nesdis.noaa.gov/datasets/ASCATData.php/ and the wider swath-data can be accessed at: http://manati.orbit.nesdis.noaa.gov/datasets/OSCATData.php. The National Hurricane Center provides a good baseline of current hurricane information on its site, located at: http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/