How to step from casual cruiser to successful blue water sailor (published January 2015)

Day sailors with big dreams might leaf through the pages of sailing magazines and wonder how to work their way up to an ocean crossing. It’s a question my husband and I often asked ourselves and one we field now that we’ve achieved a dream many years in the making. There’s no single right way, but we can tell you about our route to the open sea—one that eventually led us across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans aboard a 1981 Dufour 35 together with our young son.

Those four years of cruising gave us magical travel experiences and family time we wouldn’t trade for anything—a prize we earned by taking it one step at a time.

We started in our 20s when we re-launched a long-neglected 17-footer and explored southern Maine’s Casco Bay. As our dreams and paychecks grew, we stepped up to charter vacations and gradually got serious about selling up and sailing away. The next logical step was to enroll in a correspondence course to fill in our spotty knowledge of navigation and seamanship. But after that, well, there’s nothing logical about selling up and sailing away, not the way our culture sees things. That may be why so many dreamers stall out on the cusp of upping the ante to blue water sailing. Because just how does one progress from local sailing and textbook exercises to the wild blue yonder?

Looking back, we find three experiences that stand out in terms of making blue water sailors out of the weekend warriors we once were. The first is obvious enough: gaining open water experience, either by sailing with capable friends or through a sailing course. The second point is one that’s often overlooked by people determined to fast-track their way to the wild blue yonder, that is, by getting thoroughly familiar with the boat you intend to cruise. Overlapping with that is the third major point: developing a mindset of resourcefulness. In many areas of the world, you’ll be totally on your own in terms of repairs, and every boat will quickly develop issues out on the open sea.

ON YOUR MARK…

So, first things first, every prospective cruiser should gain open-water experience. Like many casual sailors, we tested the waters with a couple of charter vacations before setting the bar higher. When we did, the two experiences that were most valuable to us were a coastal skipper course and a weeklong delivery we joined as crew.

Because we live in Europe, we chose a British RYA Coastal Skipper course (the rough equivalent of ASA 106/108) in Gibraltar. Having completed the theoretical part of the course at home, we could apply the knowledge in a real-life setting. It was a fantastic experience that packed a lot into one intense week, including overnight sailing in a heavily trafficked area with significant tides. Those were lessons we drew directly from years later when we sailed our own boat through the Straits of Gibraltar and the Panama Canal, as well as along the busy east coasts of North America and Australia. The course also whetted our appetite for cruising because of the cultural variety of the area. We sailed from British Gibraltar to Morocco and back over to Spain, taking the time to sample local culture along the way.

We recommend looking for a course that takes place in tidal waters and includes night sailing in long, open water stretches where there is significant shipping. The best way to get your feet wet with such intimidating factors is having an experienced sailor hold your hand, or act as a drill sergeant who demands that all maneuvers—especially those you’d rather avoid—are repeated until you’ve got them down pat. Our instructor devoted a couple of long mornings to docking maneuvers in quiet marinas, for example, and the white-knuckle experience paid big dividends when we eventually cruised the Mediterranean on our own. And as far as cost went, we found that live aboard sailing courses aren’t more expensive than chartering since you share the boat with other students.

The second valuable experience we had was serving as crew on a delivery trip in the Mediterranean. For us, it was a test: could we actually handle and enjoy multi-night open-water sailing over longer distances? Our 10-day trip from Malta to Mallorca via Sicily fit the bill exactly. We found a charter company that offered crew berths on its delivery trips at very low rates, with the added benefit of serving under a professional captain. Sailors based in North America might find a similar experience by signing on to help with a return delivery after one of the east coast to Bermuda races. As things turned out for us, the weather was awful and the delivery was rushed. It was the perfect test! Though we came away on shaky legs, we learned that we really could handle round-the-clock watches in poor conditions and that night watches needn’t be terrifying—not when you have a watch buddy and an experienced captain to call on if needed. As it turned out, several other crewmembers in the three-boat delivery were just like us, casual sailors wondering if they truly wanted to commit to the next step. One became a close friend and crewed for us when we crossed the Atlantic three years later.

With those two experiences under our belts, we felt confident that our dream was worth pursuing. Still, we knew we hadn’t mastered all the skills we needed to run our own boat, which is something many fast-trackers seem to overlook before plunging straight into the open ocean. This next point is key: sailing is the easy part. What’s much more difficult is dealing with traffic in tight quarters, anchoring in challenging conditions, making decisions on things with as high a degree of uncertainty as weather forecasts, and coping with the constant repairs that are part and parcel of long-range cruising. That’s why gaining blue water experience is only one facet of your learning journey. The other is becoming familiar with and handling a range of challenges on your own boat.

GET SET…

Too many people expect to simply buy a boat and sail off into the sunset, but there’s nothing simple about it, which is a tough lesson that can become all too clear in mid-ocean. We’ve seen the sad remnants of other people’s dreams rotting away in marinas around the world, often at the first port of call after a major crossing. That’s why we strongly recommend buying and sailing the boat you will cruise on for at least a year before setting off on your grand adventure. Every boat has its own history, its own quirks and its own aching joints. For your own safety and peace of mind, you should get to know a boat before you sail away from the safety net of home.

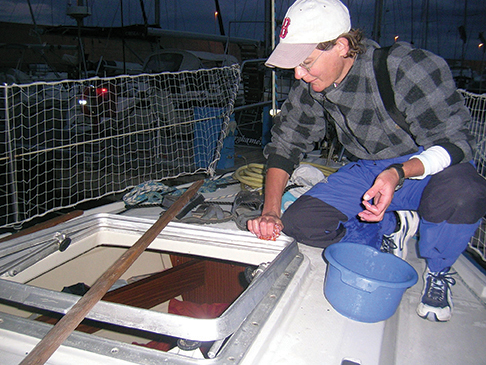

We owned our boat for eighteen months before we set sail and look back on that cycle of seasons as one of our most valuable learning experiences—a time in which we learned to walk before we could run. Over those months, we completed several short passages and made countless repairs that helped us get to know our boat, not just superficially, but deep down at the bottom of lockers, up the mast and under the keel.

The mistakes we made and lessons we learned helped get our first cruise off to a good start. We discovered what our toolbox lacked and bought what we needed while still in a familiar place stocked with parts. We also discovered that the aging engine that had checked out beautifully in our pre-purchase survey was developing problems and that replacement parts were no longer manufactured. In a year of weekends and short vacations, we bashed knuckles and toes, dragged anchor once or twice and soaked in many a contemplative sunset. Generally, we learned to call her home and our “patience” (though at the time, I felt anything but patient) eventually paid off in two enjoyable long-range cruises.

It’s not just about preparing the boat, but the crew, too. A person who buys their first cruising boat within a few months of departure of their big adventure risks being rushed and distracted by the process of cutting his or her ties to land. Conversely, the sailor who buys the boat a year or more ahead of time will get to know the vessel and can customize details to accommodate their priorities, whether that includes up-to-date electronics and safety gear, details like bunks for the kids, or just a place to stow the guitar. This sailor-owner can take the boat out, or work on it, on 50 critical weekends.

The advantage of learning aboard your own boat is that you are the boss, and you can carefully design trips to fill gaps in your knowledge. Once again, I’ll stress that sailing is the easy part. Before setting off into the sunset, make sure you can fix your boat, anchor confidently, deal with shipping and night sailing and learn to err on the side of caution when interpreting weather reports. Use your pre-departure year to work your way up gradually. From weekend day trips, you can move on to anchoring overnight. Eventually, you can try night sailing by picking a fair weather window and a familiar stretch of water; then simply head out and back. The prospect of night sailing frightens a lot of newer sailors, but it can actually be very pleasant, and it’s amazing how much you can learn in a single night. Early on in our second extended cruise, we gained a valuable refresher in night sailing within the space of a few hours by leaving Portland, Maine at sunset. Buoys were flashing everywhere, ships were coming in and out of port, and making sense of the big picture—even in a familiar port—got us right back into the swing of things. A short overnighter like that one to the Isle of Shoals gave us a manageable challenge before we knuckled down in earnest for a three-year trip to Australia.

You’ll learn more by doing overnighters or short passages on your own than you will by taking any additional sailing courses on other boats. You’ll get the feel of the boat and discover her ugly secrets. During that time, take the family out for a one- or two-week cruise and anchor every night so you’ll learn how to manage power resources, how the dinghy handles and what types of meals are practical on board. This is especially important for sailors dreaming of crossing the Pacific Ocean, since there are so few marinas along the way. If you feel you still need guidance, think about hiring an instructor to join you on your own boat instead of taking additional courses. The cost will likely be the same, or cheaper, if you are thinking of flying several people and paying multiple tuitions.

One caveat is that as valuable as a preparation year can be, I wouldn’t recommend extending it too long. You can spend a lifetime inching up to the big league, but sooner or later, you just have to take the leap and go. That’s the other lesson we learned by looking at the boats we left behind. For every sailor who succeeds in cutting their ties to land, there are a dozen others still immersed in “getting ready” for a someday that never comes. Marinas around the world are full of boats that are bigger and nicer than ours, yet we’re the ones who made our dream a reality. We didn’t wait until every detail was perfect because we knew that repairs are a constant. No sooner do you work the list down than the next item comes along, begging for attention. Being cautious is smart, but being overly cautious will get you nowhere.

GO?

So, you’ve taken a couple of courses and gotten to know your own boat. Are you ready to go? Don’t forget point number three: learning to become your own rigger, mechanic, plumber and general tinkerer. I’m not suggesting you wait to become an expert in all these areas before setting off, because then you might never leave. However, you should try your hand at a number of different projects on board and develop a mindset of self-sufficiency. Get to know your tool box, have a look at what’s hiding behind the panels and attempt a number of repairs on your own.

Consider this, an ocean cruiser will put more hours on their hull in the course of a 72 hour passage than some weekend warriors do in an entire season. A boat has all the systems of a house, packed closely in a corrosive saltwater environment where there’s no repairman on call. You’ll need tools, spare parts, and above all, resourcefulness if you are going to sail off into the sunset. We often had to cobble together solutions for things that didn’t have a direct one-to-one replacement—from the busted diesel injection pipe to a fitting in the galley sink and the patch of deck rot we discovered in the middle of the Pacific. There’s no course in resourcefulness except the one that you teach yourself, and every boat, no matter how new, will develop problems. Case in point: our 1981 sloop needed just as much work as some very fancy modern yachts. In either case, it’s a frustrated owner indeed who waits for parts and expert help rather than attempting the repairs on their own.

Therefore, you should take any opportunity you get to observe fellow sailors work on their own engine, rig, hull, deck, electronics, plumbing and more. You cannot get into ocean sailing, especially in the South Pacific, with the mentality that you can find and pay someone to help with repairs. Even if you can find help, the people offering services often make shoddy repairs. The best resource is a good manual, your brain and your fellow sailors, because the cruising fleet quickly develops into a community in which everyone helps each other. A diesel repair course may be a worthwhile investment, but looking over someone else’s shoulder or tinkering with your own engine can be just as good. Think of your buildup phase this way. Every time you pay someone else to do a job for you, a learning opportunity is lost. If you must pay an expert to do the job, act as their helper so you can learn.

So there they are, my three key steps toward blue water sailing. There are a few smaller points I’d add to the list, such as first aid certification and a mariner’s long-distance radio certificate. The latter will allow you to legally operate an SSB radio, which we list among the top couple of pieces of equipment on our boat. With it, we could receive weather information, have two-way conversations with people thousands of miles away and send/receive short email messages.

If it all sounds like too much, don’t worry, all of this preparatory work can be great fun, not to mention rewarding. Think of every step along the way as its own adventure, not just an adventure in the making. Many of us use sailing to escape the endless grind of the rat race, and these activities will give meaning to every weekend and vacation before you set off. In the rest of your free time, you can research destinations, charts and other equipment. That’s another lesson we learned, that anticipation can be, well, if not the best part, then pretty darn close.

Nadine Slavinski is the author of Lesson Plans Ahoy: Hands-On Learning for Sailing Children and Home Schooling Sailors. Together with her husband and young son, she cruised the Atlantic and Pacific aboard her 1981 Dufour 35, Namani. She is currently at work on The Silver Spider, a novel of sailing and suspense, as well as Pacific Crossing Notes: A Sailor’s Guide to the Coconut Milk Run (see nslavinski.com for more information and free resources on home schooling).