Part 1: How to transit the Panama Canal without an agent (published June 2015)

Transiting the Panama Canal is one the highlights of any cruiser’s voyage. There’s the excitement of changing oceans and doing it mixed among the giant cargo ships of the world in a historic set of locks, along with the anxiety that comes with planning to make a safe transit.

Transiting the Panama Canal is one the highlights of any cruiser’s voyage. There’s the excitement of changing oceans and doing it mixed among the giant cargo ships of the world in a historic set of locks, along with the anxiety that comes with planning to make a safe transit.

Whether you are leaving the Atlantic to start the long passages into the Pacific, or leaving the Pacific for a leisurely cruise of the Caribbean, a canal transit is a major milestone that you won’t forget. The Panama Canal itself is one of the “Seven Wonders of the Modern World.” It was a major engineering feat that was started by the French in 1881 and finally finished by the U.S. in 1914. Thousands of those who worked on the canal lost their lives to tropical disease and industrial accidents. Many of the investors lost their fortunes, too.

Today the canal locks look much like they did when it opened; giant hot-riveted black metal doors at each end, seven foot thick, rough concrete sides with inlaid ladders and hooks, and depth reader boards made of inlaid tile are accented by dark, frothing waters as the locks fill and empty. The ships are larger today than when it opened and the traffic volume has increased dramatically to about 17,000 transits a year.

TRANSIT LOGISTICS

The peak season for yachts transiting the canal is January to March, with probably three to nine boats a day going through on average. Yachts transiting the canal are known by the Canal Authority as non-commercial “hand-line” vessels. Hand-line vessels do not require the canal locomotives, known as “mules”, to bring them through the locks as the cargo ships do; the lines which control the boat while in the lock are managed by hand by Canal workers standing on the lock walls.

The peak season for yachts transiting the canal is January to March, with probably three to nine boats a day going through on average. Yachts transiting the canal are known by the Canal Authority as non-commercial “hand-line” vessels. Hand-line vessels do not require the canal locomotives, known as “mules”, to bring them through the locks as the cargo ships do; the lines which control the boat while in the lock are managed by hand by Canal workers standing on the lock walls.

Canal transit fees for yachts are reasonable, at least from a cruisers’ point-of-view. The fee for a yacht under 50 feet long is $800 and for yachts 50 to 80 feet it is $1,300. The canal actually loses money on these transits but is obliged to maintain access for small boats according to the terms of the original Canal Treaty. For an interesting look at the early Canal history, the free e-book The Panama Canal, A History and Description of the Enterprise, by J. Saxon Mills published just after the Canal was finished is a good, short read.

There are two types of “agents” available to help you set up your transit. One is accredited with the Canal Authority and the other isn’t. If you use an accredited agent, then you will not be required to post the security bond known as the “buffer.” If you don’t use an agent, then you will post an $891 buffer fee (for yachts under 50 ft) at the same time you pay the transit toll. You can request that the buffer be returned via a bank wire. It usually takes about two weeks after you complete the transit for the money to be returned.

There are two types of “agents” available to help you set up your transit. One is accredited with the Canal Authority and the other isn’t. If you use an accredited agent, then you will not be required to post the security bond known as the “buffer.” If you don’t use an agent, then you will post an $891 buffer fee (for yachts under 50 ft) at the same time you pay the transit toll. You can request that the buffer be returned via a bank wire. It usually takes about two weeks after you complete the transit for the money to be returned.

The buffer fee is intended to cover liabilities you may incur and is essentially a security deposit. It would cover, for example, the repairs if you damage one of the lock’s cement walls. That’s unlikely, but it does come into play if you should fail to meet your schedule. If you are assigned a transit time of 9 a.m. on a particular day, you can call the scheduler anytime up to 24 hours in advance and shift the date. If you change the date within 24 hours or just aren’t ready to go on time on the assigned day, for instance due to an engine that won’t start, then you lose your buffer and you won’t be able to re-schedule your transit until you pay a new buffer fee. The same rules apply if you have an agent involved. You must pay the buffer fee before your agent can reschedule a new transit date.

An agent will typically charge a yacht about $350 to $500 for managing their transit. They will handle registering with the canal, making your payment at the bank or via an account and calling the scheduler for a transit date and time. Agents will also rent you the lines and tires that are required for your transit.

There are a few disadvantages to using an agent; you are out a fair chunk of change for their services and you put one more person in-between you and the canal scheduler, which is a little like playing the kids game “telephone” where a message is passed on from child to child until at the end it is no longer recognizable as the original message. Plus, you miss the experience of interacting on a work-level with the people of the country you are visiting.

TRANSIT SETUP

To paraphrase the banditos of the 1970’s movie classic Blazing Saddles, “We don’t need no stinkin’ agents.” It turns out that all of this is very easy to manage yourself. This is due to the fact that you will be working with professionals at the ACP (Panama Canal Authority) who all speak excellent English and are, in general, very helpful.

Before you get started with scheduling your transit date, you should be sure that you have access to good communication; have a phone that functions locally and working email. Getting local SIM cards for phones is very easy in Panama and the data plans are inexpensive.

To initiate your transit, the first thing you need to do is get your vessel registered in the ACP computer system. This is done by sending Form 4405 to the Admeasurer’s office along with a scan of your passports and boat registration. If you are on the Pacific side, it is easy to take a bus or taxi to the Admeasurer office and complete Form 4405 while you are in the office. The taxi drivers know how to get to Building 729 in Balboa for the Pacific side Admeasurer. On the Atlantic side, I try to limit my visits into the city of Colon as it is not known for being very safe and is a long way from Shelter Bay Marina.

If you have your boat here, I have found it easy to set up the transit without ever going into the city. You’ll find a downloadable copy of 4405.pdf form at noonsite.com (and other websites that you can Google). Fill the form out and send the info to the Admeasurer’s office at optc-ara@pancanal.com if you are on the Atlantic side and optc-arp@pancanal.com if you are on the Pacific. Alternately, you can put the information requested on the form into the email directly: vessel name, registration number, length, beam, width, owners name, address, arrival date in the Panama Canal area, requested transit date and crew list—you do not need to include all your line handlers, just regular crew onboard.

If you have your boat here, I have found it easy to set up the transit without ever going into the city. You’ll find a downloadable copy of 4405.pdf form at noonsite.com (and other websites that you can Google). Fill the form out and send the info to the Admeasurer’s office at optc-ara@pancanal.com if you are on the Atlantic side and optc-arp@pancanal.com if you are on the Pacific. Alternately, you can put the information requested on the form into the email directly: vessel name, registration number, length, beam, width, owners name, address, arrival date in the Panama Canal area, requested transit date and crew list—you do not need to include all your line handlers, just regular crew onboard.

Shortly after you email in your information you need to follow up with a phone call to the Admeasurer’s office (443-2293 on the Atlantic and 272-4571 on the Pacific). When calling the canal offices about your transit, the easiest way to identify yourself is “I’m calling about the hand-line vessel YOUR BOAT NAME.” This is how they will look you up in their system.

Once you’ve confirmed that the Admeasurer’s office has received your paperwork, you can request that your boat get measured. Measurement is usually available within a day or two of your call. On the Atlantic side, the measurer from the Admeasurer’s office comes out to your boat slip in Shelter Bay Marina. If necessary, you may be able to have them come to your boat in the canal anchorage known as the Flats (aka ‘F-anchorage’ or the small-boat anchorage). This is a yellow buoyed area in front of the Cristobol container port in Colon. There are no dinghy docks available and no safe places to go ashore from this anchorage. On the Pacific side, the measurer comes to your boat in the La Playita anchorage or near by.

The measurer will have a stack of forms with him that he will fill out based on information about your boat. Questions will include the following: How fast is your vessel? Anything over 5 knots will do. (Note: whatever you say here, you will get to modify when the advisor is on board and you are transiting.) Do you have a bow thruster and what is its horsepower? Do you have a holding tank? Yes. Do you have a shade for the advisor (a bimini of some sort)? Yes. Do you have an enclosed head? Yes. Do you have a horn? Yes.

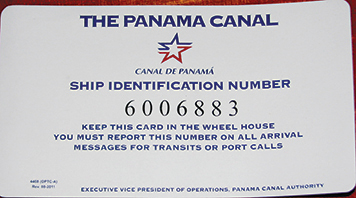

Once the measurer has completed his paperwork, you will be given a certificate that has your vessel’s official Canal Ship Identification Number. This is the unique number that is used to file your boat in the ACP computer system. It is specific to your boat, not to you the owner. If you sell your boat, this certificate should go with it and can be used on the boat’s next transit.

The measurer will measure the overall length of your vessel. If it is near the 50-foot transition point, they will usually measure very carefully. Any overhang, including solar panels on arches, anchors, dinghies on davits, etc., will be included in the measurement. Since it is a significant additional cost when you hit the magic 50 feet length, it is recommended that you do some dismantling if possible to stay under 50-feet.

You will be asked if you have the four regulation sized 125 feet lines and adequate fenders. You do not have to have these onboard at the time of inspection. You can rent the lines and plastic-wrapped tires from local taxi drivers (Tito on the Atlantic side and Roger on the Pacific side. See the Panama City Cruisers Guide available at svsarana.com and other websites for contact info). You will then be asked to sign a form whose legalese wording sounds a bit like you are agreeing that your boat is in no way adequate for transiting the Canal and that any damage is your problem. In practice, it doesn’t work like this.

You will be asked if you have the four regulation sized 125 feet lines and adequate fenders. You do not have to have these onboard at the time of inspection. You can rent the lines and plastic-wrapped tires from local taxi drivers (Tito on the Atlantic side and Roger on the Pacific side. See the Panama City Cruisers Guide available at svsarana.com and other websites for contact info). You will then be asked to sign a form whose legalese wording sounds a bit like you are agreeing that your boat is in no way adequate for transiting the Canal and that any damage is your problem. In practice, it doesn’t work like this.

Damage caused by you, such as a failed line or a failed cleat is your problem. Damage caused by canal ships or other transiting vessels that clearly misbehave will generally be covered by the canal. You’d have to document the issue and have witnesses. Your advisor would probably already have had to report any incident that came to this level of problem. Then a formal hearing is convened by the ACP. You can be represented here by a lawyer. These incidents are rare, but they do happen.

You can ask the measurer to put your desired transit date on the forms he is turning in to the scheduler. This might be phrased like: The earliest transit after April 4th. A measurement inspection is good for up to 60-days. Once you have been measured the inspector will leave you with a number of forms. Two of them relate to payment. You have two possible ways to pay the transit and buffer fees. You can pay with cash at one of the two designated banks or by bank wire. There is a Citibank designated in Colon on the Atlantic side and another in Balboa on the Pacific side that accepts transit payments. If you are paying by cash, you take the two forms to the bank along with your roll of U.S. dollars. I suggest you do this in the morning and not over lunch hour so that you are more likely to catch the employees who are authorized to process transit fees at their desks. As I’ve already alluded to, I’m not a big fan of walking around Colon, especially with $1,800 cash in twenties in my pocket. If you do, either take a taxi or have the shuttle bus driver from Shelter Bay drop you close to the bank and point you to where it is. The bank on the Pacific side in Balboa is easily accessed via a taxi or bus.

You can ask the measurer to put your desired transit date on the forms he is turning in to the scheduler. This might be phrased like: The earliest transit after April 4th. A measurement inspection is good for up to 60-days. Once you have been measured the inspector will leave you with a number of forms. Two of them relate to payment. You have two possible ways to pay the transit and buffer fees. You can pay with cash at one of the two designated banks or by bank wire. There is a Citibank designated in Colon on the Atlantic side and another in Balboa on the Pacific side that accepts transit payments. If you are paying by cash, you take the two forms to the bank along with your roll of U.S. dollars. I suggest you do this in the morning and not over lunch hour so that you are more likely to catch the employees who are authorized to process transit fees at their desks. As I’ve already alluded to, I’m not a big fan of walking around Colon, especially with $1,800 cash in twenties in my pocket. If you do, either take a taxi or have the shuttle bus driver from Shelter Bay drop you close to the bank and point you to where it is. The bank on the Pacific side in Balboa is easily accessed via a taxi or bus.

Alternately, you can email the Wire-service office at the canal and receive the wire-transfer instructions. Send an email to customerdeps@pancanal.com requesting the information. The office is very helpful and will answer questions via email or phone. Your bank wire will be routed through Citibank, New York. It may take a couple of days to clear—longer if there are holidays in your home country or in Panama.

The second form that you received to make your payment was a form for requesting your buffer deposit back. It is easiest to have it bank wired back to your account. This usually takes about two weeks after your transit is successfully completed.

After 6 p.m. on the day you have paid your transfer fee at the bank or after you have gotten confirmation from the ACP wire-transfer office that your wire has been processed, you should call the Scheduler’s office (507-272-4202). The office operates 24hr/7days a week and is staffed by English speaking personnel. Tell them you are the Hand-line Your Boat Name and would like to get your transit schedule for my south bound (or north bound) transit. The first time you call there will usually be a bit of paper shuffling and looking things up. You will then be given your transit date. I like to ask what other yachts are scheduled to go through with me on that date. That way I may be able to hook up with them in the marina or anchorage and discuss logistics before we go.

After 6 p.m. on the day you have paid your transfer fee at the bank or after you have gotten confirmation from the ACP wire-transfer office that your wire has been processed, you should call the Scheduler’s office (507-272-4202). The office operates 24hr/7days a week and is staffed by English speaking personnel. Tell them you are the Hand-line Your Boat Name and would like to get your transit schedule for my south bound (or north bound) transit. The first time you call there will usually be a bit of paper shuffling and looking things up. You will then be given your transit date. I like to ask what other yachts are scheduled to go through with me on that date. That way I may be able to hook up with them in the marina or anchorage and discuss logistics before we go.

You should call the scheduler back at regular intervals to check that your scheduled transit date has not been adjusted. Call at least three days before the scheduled date and follow-up with a confirmation call each day after. The evening before your transit, call the scheduler after 6 p.m. In this call you will receive the expected arrival time of your advisor. On the morning of your scheduled transit it is also a good idea to call the scheduler one more time to check that there are no changes.

TRANSIT TIME

On the day of transit you should have your VHF radio on and monitoring channel 12. On the Atlantic this will be Cristobol Control and on the Pacific it will be Flamenco Control. They occasionally will call your vessel to let you know of any advisor arrival time changes. These changes may possibly be for an earlier arrival of your advisor.

You should have everything ready prior to the day of transit. Don’t expect to fuel up on your way out, as this is Central America and fuel availability just might be scheduled for mañana. On the Atlantic side you will be told to meet your advisor in the F-anchorage, which is marked by four yellow buoys and is located just south of the container port dock. On the Pacific side you will normally be told to meet your pilot just outside of the canal near one of the early red side entrance markers—this will be near the La Playita yacht anchorage. You will typically have to wait anywhere from 15 minutes to a few hours before your advisor shows up. If there are multiple boats transiting with you, the advisors for these boats may not all show up at the same time.

Once your advisor is onboard it’s time to start your transit. The advisors are (almost) all very friendly and competent. They all have full-time jobs working in senior positions on the canal. They may manage pilot boat crews, drive dredges or perhaps manage a canal security team. Advisors are usually very ready to tell you all kinds of interesting details about the Canal and what they do for their regular job. They work part-time as advisors on their days off. To become an advisor, they must complete specialized training and an apprenticeship on board yachts transiting the canal.

Most advisors do this to earn extra money and to meet interesting people from around the world. During the busy yacht transit season, there can be a shortage of advisors available on certain days causing re-schedules and delays.

The single most important thing you can do in advance of your transit through the canal to make it fun and safe is to go through yourself on someone else’s boat as a line handler. It’s a great time and the knowledge you gain will reduce the anxiety of your transit and help you make it an experience of a lifetime.

Paul Lever and Chris Hunter have been cruising full-time for the past four years. They’ve ranged from Seattle to Mexico, and Panama to Cape Bretton and Nova Scotia. Their Outbound 44, Georgia, is currently in French Polynesia after another successful Canal transit and a visit to the Galapagos. Follow their adventures at svjeorgia.blogspot.com.