During their voyage around the world, they experienced cultural immersion through the local cuisine (published June 2013)

When my husband Seth and I first set out on our global circumnavigation, I thought almost solely of the sailing. I envisioned great stretches of ocean with only a bird to break the horizon. I imagined our 38 foot cutter Heretic romping before the trade winds or battling a gale. I quickly came to realize, however, that half the fun of it was the ports where we called. I had traveled before, in the more traditional manner of airplanes and hotels, so sightseeing and dipping into another culture was not a novel experience. What was new was the cultural immersion inevitable when voyaging aboard your own boat.

The primary cause for this immersion is that you bring your home with you. Cruising allows you to visit places where there are no hotels, no airstrips, sometimes even no people. But more than this, it requires you to live in a place rather than simply visit it. Cruisers don’t just see Fiji’s coral reefs, but its machine shops and hardware stores. And, they meet its fishermen, farmers and fruit vendors. Instead of simply enjoying the local cuisine at a restaurant, cruisers learn to prepare it themselves, choosing from the ingredients available at the vegetable market and cooking it in their own galleys. There are many aspects to living aboard a sailboat that I enjoy, but experimenting with the cookery of each port is one of my favorites. While voyaging on Heretic, I often adopted the culinary habits of the cultures in which Seth and I found ourselves. In doing so, I discovered how strongly cuisine suits its provenance.

Adapting to local eating habits began as soon as we left our home port of Blue Hill, Maine and reached the South. We developed a liking for hominy grits and cooked them every morning that we spent in Beaufort, North Carolina. A dish that would have been strange among the spruce clad islands of Maine tasted perfect when we looked out the portholes at grassy marshland, wild horses and white Neoclassical houses.

Neither of us could drum up equal enthusiasm for conch once in the Bahamas. Seth and I tried hard to adapt to the ubiquitous shellfish, tenderizing it, roasting it, and even obliterating it in hot sauce, but to no avail. The tough, rubbery conch was only palatable when served battered and deep fried at a restaurant. We could enjoy the fish of these tropical waters, however, especially when Seth caught a large yellowfin tuna.

Our next port, Jamaica, provided our first encounter with an overflowing open-air market. The vendors piled their stands with deep red tomatoes, thick heads of lettuce and big bunches of yellow plantains. From the humid hills came the pungent beans of Blue Mountain coffee, an exciting treat after months of dulling our taste buds with instant Folgers.

Beginning in Jamaica, Seth and I discovered the superlatively better taste of fresh fruit from their cold-stored cousins in northern supermarkets. Mangoes, growing in such profusion that many fell and rotted before they could be picked, became our staple snack in Panama and again on the lush volcanic islands of the Marquesas. We learned to fry ripe yellow plantains in the Galapagos, and we tried the fat red ones that grew on Nuku Hiva.

Polynesian grapefruit, although green on the outside and almost white within, spilled juice all over the cockpit and contained an explosion of flavor far beyond the ruby ones I was used to. Pineapples were similar. Starfruit and papaya growing on trees in the Cook Islands actually had a taste: they weren’t the bland novelty fruits occasionally advertised in Shaw’s or Safeway. Bananas weren’t huge perfect yellow fingers, but stubby spotted ones sweeter than any I had eaten before. They, too, were so abundant that farmers sometimes insisted on selling us the whole tree rather than just a bunch of four or five.

Sailing among the Polynesian archipelagos, Seth and I adopted more culinary habits than the tropical fruit. French baguettes were the only cheap item in the grocery store, so we ate an entire crusty loaf a day. We discovered poisson cru, a traditional dish of raw mahi mahi marinated in lime juice and served drenched in coconut cream with sliced cucumbers and sometimes tomatoes. If there were any available, Seth and I occasionally added bell peppers. It became our favorite dinner and we did almost nothing else with the mahi mahi that we caught or purchased.

But when Heretic ducked out of the cyclone belt and sailed to New Zealand, poisson cru and tropical fruit no longer tasted right. We adopted the local cuisine once more, the food that fit the place. Beets are a favorite vegetable in New Zealand, so Seth and I ate them more and more often until we were even putting them on our hamburgers as the Kiwis do. Fried eggs, lamb, venison sausages and even Marmite graced Heretic’s galley.

In Fiji the following May, Marmite ceased to be appropriate. Fiji lies close to Asia and has a large Indian population, so we found roti bread, painfully hot chili peppers and Japanese eggplant for sale in the market. Bok choy and Chinese long beans became our green vegetables and taro chips, cooked in the frying pan, our snack. Bananas and plantains grew in abundance again. The tomatoes were a ripe red and the cucumbers and carrots big but flavorful. Asked to Sunday brunch by some Fijians, we found curried lentils side by side with wild boar hunted the day before, freshly-caught snapper and boiled taro harvested from their fields.

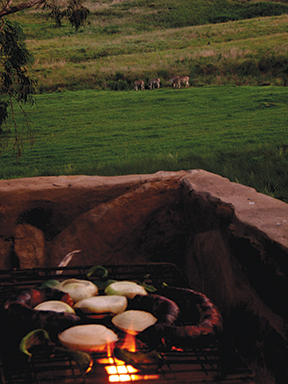

The markets in Vanuatu sold similar vegetables and boasted grapefruit equal to those we had eaten in French Polynesia. But when we reached Australia, Seth and I turned back to Marmite and fried potato wedges dipped in sweet chili sauce. The pattern continued across the Indian Ocean: Japanese eggplant, coriander and watercress appeared on Tamil-dominated Mauritius, but we reverted to more Western cuisine upon reaching South Africa. Even there, where the well-stocked supermarkets could supply almost anything we wished to cook, Seth and I slipped into local habits. Braai, or barbecue, is so popular that meat is sold in special braai packs, which include all the necessary items: sausages, steak and lamb chops. Every rest hut in every game park comes equipped with a braai pit. Suddenly, after months of eating an almost wholly vegetarian diet—we had only the smallest fridge aboard Heretic—we were barbecuing all the time. We started to snack on biltong, jerky made most often from beef but also from ostrich and antelope. We even tried farmed springbok and kudu meat, which tasted very much like tender lamb and beef respectively.

Crossing the Atlantic returned us to the verdant Caribbean. Again, we encountered a plethora of fruit. Dominica especially harbored so much that the informal coast guard of local guides would sell mangoes, passion fruit and papaya to the anchored boats for a song. Our particular guide, Martin, supplied us with so many mangoes for free that we ate almost nothing else. Martin was a trained botanist, so his tour of the island centered around edible plants: he sliced up pineapples and papaya for us; we picked mangoes at every stop; and, he showed us fresh bay leaves, lemongrass, cinnamon and cocoa. At the immense vegetable market in town, Seth and I experienced a sense of déjà vu as we chose our bananas, plantains, chili peppers, ripe tomatoes, fat cucumbers, bright green beans and a prickly but creamy sweet soursop.

When we sailed north from the tropics, bound back to Maine, I knew that Seth and I would soon revert to the northern cuisine we had been raised on. Crisp apples, butternut squash, corn and tomatoes fit New England, just as mangoes fit Dominica and taro fits Vanuatu. Because Seth and I had experimented with the foods of each country at which we had called, eating what tasted most appropriate, Heretic’s galley still carried evidence of many of her ports. There was raw sugar from Barbados, cinnamon and cocoa from Dominica, an unopened package of biltong from South Africa, a sealed jar of Marmite from our Australian provisions and some fiery red chili peppers remaining from Fiji’s markets. Not only had Heretic brought me to all these different places, but her galley had led me to live in them.

Ellen Massey Leonard recently completed a four-year 32,000-mile circumnavigation with her husband Seth aboard Heretic, their 38-foot semi-custom cutter. Their voyage took them westabout via Panama, the milk run route and the Cape of Good Hope. Now based in landlocked Switzerland, Ellen is working on a book about their circumnavigation.