Flexible plans mean good seamanship and unexpected rewards (published May 2015)

Sailors setting out on long voyages rightly devote a lot of time and energy to preparing and provisioning their boats and to researching routes, ports, regulations, weather and other factors. This is important and makes offshore sailing safer. But one of the most essential safety features on a voyage is the more amorphous quality of flexibility.

Every sailor knows the saying that plans are written in sand at low tide. While it is important to make plans, it’s equally necessary to have the flexibility and imagination to throw those plans out the hatch. I can’t count the number of times my husband Seth and I did this on our circumnavigation. Sometimes we changed small plans, such as detouring to Flinders Island in Australia on a friend’s recommendation. A couple of times we changed big ones: when repairs kept us in Panama for two months, we decided to add an entire year to our voyage and spend hurricane season working in New Zealand.

Most recently, in June 2014, Seth and I decided not to attempt a transit of the Northwest Passage. We had been working towards our possible attempt for a year. Our new-to-us cold-molded cutter Celeste had been in the care of Platypus Marine boatyard in Port Angeles, Washington (recommended to us by a shipwright friend of ours) getting a new barrier coat on her hull and a new Yanmar diesel to replace her 30-year-old engine that belched clouds of blue smoke. Seth and I had amassed safety gear, spare parts, tools, charts and provisions. I had worked hard at sponsorship proposals for specific equipment and had sorted out Celeste’s paperwork. Both of us had spent a good six months foregoing weekends in favor of our paid work in order to be able to spend the summer on Celeste.

Nearly all of this we would have done for any voyage, not only the Northwest Passage. On other voyages, however, the kind of exhaustion that these preparations cause doesn’t matter so much. Timing your passages—even with regard to cyclone seasons and winter gales—isn’t so unbearably precise as the ice window of the Canadian Arctic. So you can catch your breath before casting off or rest in your first port after the flurry of departure. For example, after a hectic month in Mauritius’s crowded capital preparing for our passage to South Africa, Seth and I pulled into Reunion Island for a week of mountain hiking, French food and relaxation. That week put us on the edge of Indian Ocean cyclone season, but we hadn’t pushed it too late and could make the notoriously rough crossing with rested minds and bodies.

The Northwest Passage doesn’t allow that kind of flexibility with timing, which means—perhaps counter-intuitively—that sailors must be doubly flexible. On past voyages, Seth and I have set rather inexact parameters: while in Panama in 2007 we intended to be in Polynesia by June in order to reach New Zealand by November to avoid cyclones. When we didn’t arrive in the South Pacific islands until nearly July we still thought we could make New Zealand, and we did. That wouldn’t do for the Northwest Passage, however. The sea ice only melts sufficiently to let a boat—any boat except perhaps icebreaker ships—through from the middle of August to the middle of September. Certain choke points only free up—if at all—for a few days, so you have to be there on those days or you miss your chance. Even then, you may not get a chance. In the Arctic, the elements, and not you, are truly in control. Seth and I had drawn up a schedule with the idea that if we were late at any of our arrivals, we should re-evaluate our attempt.

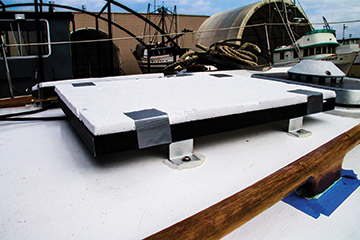

The first item on our schedule was a launch date of June 10. By the time June 10th dawned, Seth and I had been working nonstop 12-hour days on Celeste for a couple of weeks. Not only did we have all our anticipated projects to do—installing solar panels and other equipment, assembling our Jordan series drogue, varnishing and painting, re-doing some plumbing and servicing seacocks—we had also discovered a rat’s nest of suspicious electrical circuits. Every one of them had to be traced and removed, and the circuits we wanted to keep had to be redone with marine grade wire. So we missed our June 10 launch date.

At the back of our minds we were already re-assessing our prospects for the Arctic but, being overly optimistic, we just worked even longer hours, at one point staying at the boatyard until midnight. On June 20 we launched, which was a real feat considering that our three-page list had included such multi-day projects as “Remove port-side Dorade vent and mount solar panels.” We knew we had to do sea trials and troubleshoot such minor problems as our cabin heater burning so hot that it melted the Sikaflex around the chimney—but we still intended to attempt the first part of our voyage, a crossing of the Gulf of Alaska to the Aleutian Islands.

By this point, both of us were thinking out loud about going somewhere other than the Northwest Passage. The timing was much too tight: when we reached Neah Bay at the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca—our departure point for the Pacific—it was June 24, only three days before we had meant to arrive in the Aleutian Islands on our original plan. We would be stressed and rushed for the entire voyage if we attempted to transit the Arctic, not a safe recipe for such demanding latitudes. So we decided to play this Gulf of Alaska crossing by ear. The wind looked favorable, so if we arrived in the Aleutians early and felt ready to head north, we would. If the weather changed and it was better to sail for Prince William Sound or Kodiak, we would make landfall there and spend the summer exploring those waters. If things turned sour, we had Vancouver Island to starboard for the first few days. In other words, we were heeding our own advice to stay flexible.

The one thing we hadn’t made allowance for was our state of exhaustion. Neither of us had been aware of it while we pushed ourselves to ready Celeste. But once reaching out from Neah Bay, the bow lifting to the Pacific swell, we were both overcome. Seth came close to vomiting, for the first time ever. I burst into tears for no reason and then was sick on my first night watch. Neither of us were handling the boat as well as we know we can in normal circumstances. Although the wind was on our quarter, a big swell from a storm off Hawaii was hitting our southeasterly swell at a 45 degree angle, which didn’t help the seasickness. On top of all this, something was wrong with our windvane so we were hand-steering. The words “Vancouver Island” became more and more frequent. But as is so often the case with exhaustion, it saps you of the ability to make decisions. So we carried on, miserable, for two and a half days. Then our jib blew out its clew and made our decision for us. We changed course for Winter Harbour, the most northwesterly bay on Vancouver Island.

It was beyond doubt the right decision. After two and a half days of rest and one day of repairing the jib and our self-steering vane, we felt better than we had all year. The quiet green of the forest, the chorus of birds in the trees, and the friendly people living in the tiny boardwalk town calmed our nerves frayed from a year of over-work. We anchored Celeste in a deserted inlet after a night on the government dock and listened to the lap of water on her hull. A sea otter floated by on his back, curious about us. We launched our dinghy and rowed up to a tidal lagoon where black bears munched the marsh grass. It was the best day we’d had in months and refilled us with all the energy we’d lost.

When we set off on our next passage, north to Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) we hardly felt the swell, despite the fact that it hadn’t yet laid down. We tended Celeste alertly and confidently and felt joy in her speed as she flung aside the waves. This might not have been the voyage we’d intended, but it was the right one for us at that moment. We had done well to stay flexible and ignore the voices telling us we’d failed. Where was the failure in beautiful sailing through some of the richest wilderness on earth?

Circumnavigator, writer and photographer Ellen Massey Leonard splits her time between her classic cutter Celeste and working in Switzerland where she is completing a book about her voyage around the world at age 20. She most recently sailed from Washington State to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands and plans to continue north to the Arctic in 2015. She was pleased to have Katadyn, Platypus Marine, Rolls Battery, OCENS Satellite Services, ZEAL Optics, and Mantus Anchors agree to sponsor her northern voyage. The 28-year-old chronicles her adventures at www.GoneFloatabout.com.