It’s a virtual certainty that problems will arise at sea. Solutions are not always as inevitable. The goal is to minimize the number and severity of the problems and handle them with grace and composure. (published September 2015)

Spain or bust: as always, it could have gone either way. Prior to our departure from Jamestown, RI in June, preparations had been thoroughly reviewed and executed. The Swan 56, Moondance was a tried and tested vessel ready for sea. For most of the crew, the passage from Jamestown to Spain by way of the Azores would be their first transatlantic crossing, although most had sailed to Bermuda and back several times and completed other sailing milestones. With eight people onboard, we had a wide variety of experiences and preferences, and we could either turn that into an asset or a liability. How we would treat each other, deal with the extended time at sea and the inevitable problems that would arise was an uncertainty.

Michael, Moondance’s owner, had carefully considered the crew selection. Politeness and respect for others was high on his list of requirements. With a wide variety of ages and experiences, we could learn a great deal from each other and benefit from the energy and knowledge base from young and old alike. Those qualities provided a foundation upon which we could fabricate solutions to most things that were to confront us.

As we departed Jamestown in moderate southerlies, we beat out of Narragansett Bay and began the trip by heading in a southeasterly direction towards a meander in the Gulf Stream. It was not the shortest route to the Azores, but it would get us south of a cold front that was to line up along the north wall of the Stream. The route would get us into warmer water where the wind would be consistent up and down the mast rather than being affected by a marine layer of cold air which allows stronger wind aloft to drop off to nothing at the waterline. Springtime in cold water can be famous for those conditions, which show 20 knots of wind at the masthead and glassy-calm water on the surface of the ocean. Get to the Stream. Enjoy the warmer water while getting more effective use from the available wind, and benefit from an eastward flowing current.

Decades ago, virtually all passages were accomplished by hand-steering around the clock. Helmsmen changed and gained experience driving in virtually all conditions. With the introduction and increased popularity and reliability of autopilots, hand-steering has, in many cases, become an occasional activity. As a result, during deliveries now, I often require that half of the watch is spent hand-steering during the initial stages of the passage. That practice helps everyone get better acquainted with how the boat handles, how the sails need to be set in order to minimize loads on the autopilot and prepare for driving the vessel in heavy weather conditions which may not be suitable for an autopilot.

The cold front that was forecast to line up along the north wall of the Gulf Stream performed as advertised. Lightning lit up the night sky to the north of us, and winds built to 30 to 35 knots. Hand-steering for half of the watch stretched the capabilities of some of the crew, but all were up to the task, eventually enjoying the experience and the joy of sailing a well-designed and built sailboat in brisk conditions. As Moondance cut through the waves, the people driving got used to handling her. Over a couple of days, the winds began to subside, making the task a little easier, and allowing the crew on deck to enjoy the clearing night skies and driving towards one star or another. The experience was about to come in handy.

Early in the passage the autopilot began to act up. When sailing shorthanded, that can be a significant problem. It’s happened to me on other passages and is worth remembering when planning crew requirements. With eight people onboard, it would be inconvenient, but it wasn’t critical when the autopilot finally stopped working. The entire crew was well prepared to drive in brisk to heavy weather conditions, and they could adapt to whatever would lie ahead.

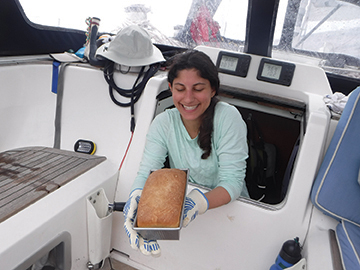

The time wasn’t all spent driving, happily enough. Prior to departure, Michael had told everyone that we would each be responsible for giving several “TED Talks” (see: https://www.ted.com/talks), about topics which interested us. Jackie, the cook onboard, gave a hands-on demonstration about how to bake bread while offshore. Everyone helped to knead the dough, even if only briefly. Tom, a retired Wall Streeter and teacher, talked about teaching economics. Matt, a young engineer, gave us some insights into heating and air conditioning and what lies behind the ceiling in a commercial building. Cam talked about some of the cancer research in which he is involved, and Dana provided us with some much needed background on the Azores, among the many other topics.

The Azores is a welcome respite in any transatlantic passage, partially because of the welcome sighting of land, partially because of the fresh local food, and largely because of the friendly people who live there. Horta, harbor paintings, vinho verde and Peter Café Sport are all uniquely inviting, but that is just the beginning of it. To explore further, the crew rented motor scooters and tempted fate by cruising around Faial. Without injuries but armed with stories, they all returned safely to the boat for the next leg of the trip: Horta to Sotogrande, Spain through the Straits of Gibraltar.

The approach to the Straits can be a cause for some trepidation. It’s always a cause for heightened awareness. The shipping traffic is crowded and relentless. With current that is always flowing from the west, when the wind is out of the east, the waves can be steep. When leaving the Mediterranean, tacking angles are less than ideal due to the current. For our own approach to entering the Mediterranean, we decided to make landfall northwest of Gibraltar in order to avoid shipping traffic that was in the process of turning at the western mouth to the Straits.

Winds south of Cape Vincent can be brisk, however, not unlike the winds around Point Conception along the California coast. The winds of the Portuguese Trades come whistling down from the north along the Portuguese coast and splay out towards Cadiz. With landfall south of Cadiz, we were able to quickly get past the strongest winds, and cross inside of the shipping lanes before ships turned as they entered or departed from the Straits. Once inside of the shipping lanes, we only needed to contend with coastal traffic or ships actually entering Gibraltar’s harbor. Heightened awareness is required throughout the passage through the Straits. However, since the ferries to Tangiers are fast and leave frequently, ships entering and departing the harbor always seem to be underway.

Soon after rounding the Rock of Gibraltar at the eastern end of the Straits, we worked our way up the Spanish coast in the early morning light to Sotogrande. The calm night breezes we experienced through the Straits and the quiet morning sail to our destination allowed me time to think about what I learned on this passage that made it special. While the qualities are not unique to this passage, it was once again reinforced that mutual respect, politeness and preparation go a long way towards creating a joyful, memorable experience. Luck favors the well prepared. Politeness builds lasting friendships.

Find out more about the journey on Moondance’s blog http://moondance2015.com/ and about Bill at www.WxAdvantage.com.