How to successfully navigate the clearing in and out process as you cruise, and the valuable cultural experiences that make it worth the effort (published March 2015)

After arriving in a new port once a long passage has been completed, the fatigue of the rotating watches fades away and is replaced with anticipation, excitement and a little apprehension about your arrival. You’ve just completed a multi-day voyage, all of the crew are still with you and you didn’t hit any of the crunchy parts as you approached land near the new port. Now you have to start thinking about winning the Cruiser’s Scavenger Hunt.

Once into smooth enough water you raise the yellow quarantine or ‘Q’ flag on your starboard spreader flag halyard. It is the international signal flag that indicates you Request Pratique, i.e. that you wish to clear in. Watch the giant cargo ships as they enter port from a distant country. They will be flying the Q flag, often along with the red and white pilot-on-board signal flag.

Cruisers sometimes misuse the Q-flag. You will hear a cruiser say they are going to “yellow-flag” the next island. This means they plan to anchor in the following country, raise their Q-flag and not check-in at all. Perhaps they will stay the night, perhaps a week. This practice is accepted in some countries if you are far from a port-of-entry where you could check-in, or if you are not going ashore and are only staying briefly. In other countries it can get your boat impounded and the crew restricted to the ship in addition to incurring significant expenses before you will be allowed to leave. I would not suggest this approach when landing in the U.S., where you’re very likely to have your boat impounded. Remember, however, that international maritime law does allow for a temporary stop if you experience a legitimate medical, mechanical or weather-related emergency.

With the Q-Flag flying and the anchor set in the new port, the captain of the vessel, or more technically the master, must complete the clearance process. Usually you head to the port captain’s office first. Here, with a little bit of luck, you’ll receive the information you need to win the game. That’s the list of items on your team’s Cruiser’s Scavenger Hunt list that you need to obtain before you can officially be considered checked into the country, along with the list for the finals of the game—what you need to successfully checkout. Before you have the list, it’s a little like playing Jeopardy without knowing the categories.

Getting information on how to clear in to a country prior to leaving your last port is generally helpful. Noonsite.com has some helpful info, although it can be lacking in the details or the latest updates. Other cruisers are a useful resource, but can be at times an unreliable source of information. There’s a tendency for the cruiser grapevine to grab onto pieces of information and keep passing them around as if they are gospel and up to date regardless of their accuracy or age. If you drop your hook in a new port and there are other cruisers already there in the anchorage, then their info is undoubtedly more up-to-date. For the most part, they have successfully just completed at least the first part of the game.

Well that depends. Not only does each country have its own rules but within a country, rules may be interpreted or applied differently at each port or, worse, within a single port the rules may be applied differently according to which official you are dealing with and whether or not they’re having a good day. The day of the week can modify the rules. Don’t take it personally, it’s just the way the game is played sometimes.

Your first task is to find the office you need to begin the process. If you are entering a port that has had lots of cruisers visiting over the years, like in the Eastern Caribbean, then it will usually be quick to either locate the clear in office or you’ll be able to ask around and find it without much trouble. You are looking for buildings that house the Port Captain, Customs, Immigration, Capitainerie, Douane, Aduana or similar names. I specifically said buildings that house because signage can be in short supply or sometimes just does not apply—as in, that’s the building that had the Port Captain’s office five years ago before they moved it a half mile inland.

Before you actually start looking for the first office to start the game, you’ll need to determine, or at least take a reasonable shot at understanding, what the rules are for who shows up. The rules fall into the following rough categories: 1) Only the master may come ashore. 2) All crew must come ashore. 3) No one is allowed ashore until you are visited by the officials. 4) You can’t do anything without an agent.

In most cases where #1 is the rule, it is usually fairly easy to get forgiven for thinking it was rule #2 and arriving with crew in tow. It is nice to get this correct, though, as you don’t want to start out on the wrong foot with the officials. Since they are the local referees, they can make the Scavenger Hunt game very difficult.

Speaking of showing up and getting off on the right foot, dressing appropriately is, shall we say, appropriate. In many Central American and South American countries, little boys wear shorts. And the old adage applies, “If you don’t want to be treated like a child, then don’t dress like one.” Plan on long pants and a collared shirt that is clean, hair brushed and sun glasses off while inside. Ladies, don’t show up in your bathing suit dressed like you are hunting for a rich Mr. Right in Miami Beach, moderation will go a long way here.

When cruising the tropics, the offices that you enter to handle clearance usually fall into two temperature ranges. Stiflingly hot and humid with at best a small ceiling fan or two slowly turning overhead, or alternately, an icebox where the air-conditioning has been turned down to sub-polar regions. Just remember when you are standing in what seems like endless waits in the stifling heat the agents behind the desk have been there all day too, most likely wearing an official uniform.

Americans usually go into official offices ready for business. A quick nod and then it’s “let’s get this done.” Most of the rest of the world does not run this way. Greet each person you initially approach with an appropriate, polite time of day greeting. You can gain another level of points if you can mumble something out in the local language: Buenas Dias, Bon Dia, Bonjour.

Now that you’ve made eye contact and swapped greetings, you can start explaining that you wish to clear in. This often elicits a response for a document you don’t have. That’s because you are in the wrong office and should have gone somewhere else first. Accept this with a gracious smile and see if you can get the person to tell you the specific order of each office you need to visit and where they are located. Without a common language this can be trying. Why all the offices required to clear a boat into a country are not in one place is a mystery lost to the ages.

Clearance fees are always a hot topic of discussion among cruisers. This is primarily because cruisers are, number one: cheap. And number two: often think that the countries should freely welcome them as they will be putting so much money into the local economy. All right, obviously not all cruisers are like this, but there are enough that cruisers have earned this characterization. In some locales, cruisers do add significantly to the local economy. In many, other types of tourism dwarf anything that cruisers might spend.

The fees that are charged for clearing in and out seem to be set whimsically. They have no apparent rhyme or reason. A country in dire need of foreign exchange might be free, or might be hundreds of dollars. Most countries charge a nominal fee—anywhere from US$5 to $75. Countries like Colombia, Panama and Ecuador can be expensive to enter. You may be able to pay in US dollars or Euros at the clear in offices or rarely with a credit card. If you can’t, with a little bit of luck there will be an open bank with a functioning ATM attached nearby that will allow you to retrieve some local currency. If not, the Scavenger Hunt will probably extend to a second day.

Countries that require an agent for clearance are usually more expensive, but not always. In Colombia, it will cost 200,000 pesos (about US$92) to clear in and out of Cartagena with a local agent if you are staying five-days or less. If you want to stay longer then you’ll need a Cruising Permit that will triple the costs. Panama does not require an agent. It does require a visa purchased at US$100 per head for each crewmember that stays longer than 72 hours, plus a $192 annual cruising permit and additional $30 if you are visiting Kuna Yala (the San Blas islands). A stop at the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador will set you back about US$1,000 by the time you pay all the entrance, agent and park fees.

You should try and start the Scavenger Hunt early on a weekday during normal business hours. Some countries offer no-fee 24/7 clearances. Others charge significantly for overtime costs. If the office is open Monday to Friday 8 a.m. to noon, 1:30 p.m. to 4 p.m., then any time spent working on your paperwork outside those hours might incur overtime fees, no matter whose fault it might be that the process is taking a long time.

I find the most grinding issue with fees is the nickel and dime way some countries approach it. You might have five different organizations and officials board your boat where you’ll get a trash inspection fee of $2; a health certificate for $1.50; a $100 fumigation certificate, even though none was done; $25 for Immigration; $30 for copying and transportation; and $25 for Customs. At times it seems never-ending and not clear if all of it is actually “official.”

Patience and persistence are important attributes of a successful Cruiser’s Scavenger Hunt player. It really can take three or four days to complete an uncomplicated check in at certain places. The reasons are many: You have to take a taxi out to the airport 40 kilometers away to see customs (Playa Cocos, Costa Rica). The port Captain went to visit his family and will be back mañana (Porvenir, Panama). (Note that in this case mañana does not mean tomorrow. The applicable translation is “not today.”) Here is your temporary visa, next week you need to go into another town to get your real visa (Balboa, Panama). It is a national holiday and so is tomorrow (many).

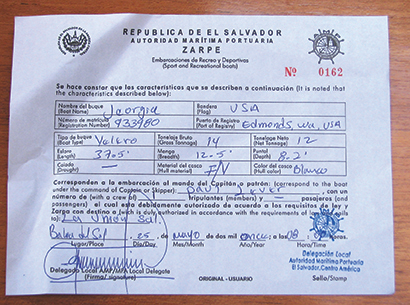

Clearing out is usually easier. You already know where the offices are located, you hopefully know what order you need to visit them in, and you are local enough now to know what days and times they will be open. The end result of your clearance papers is a clearance document. In Spanish speaking countries this is called a “Zarpe.” It indicates that you have officially checked out of the country and don’t owe any debts there. The next country along the line will most likely require a correctly completed Zarpe from the previous country to clear in. Because of this, it is important to check your paperwork closely before you leave each office. Showing up in a new country with improper clearance documents can make the next check in process your worst.

Adding and subtracting crew to the boat is where many of the clearance paperwork mistakes happen. Make sure that if you have crew who are leaving the boat to fly home, that you have done the appropriate steps in this country to remove them from the boat’s crew list. This usually requires a trip to Immigration, but in some countries you just fill out a new crew-list without the missing crewmember on it when you checkout. Adding crew is similar.

The historically Spanish countries tend to be very strict on Zarpes and entrance procedures. Surprisingly, the French speaking countries, where bureaucracy was invented, are some of the simpler ones to clear into. Lassez-faire.

Now you might think this is all a bunch of developing nation, tin-badge bureaucratic nonsense, “Why can’t they just be efficient like ‘our’ country?” Interestingly, the U.S. is one of the more convoluted and expensive countries for cruisers to visit. If you are entering the U.S. on a cruising boat and are from a country with a visa agreement with the U.S., that agreement generally doesn’t apply if you arrive by boat.

You’ll need to obtain a B1/B2 visa in advance. You are supposed to get that from the U.S. Embassy or Consulate in your home country. This is an in-person visit, so if you don’t live in the capital you might need to incur the costs of flying there for your interview and staying overnight. You pay something like $160 for the application and then an additional smaller fee if you get accepted. Then when you arrive on your boat in the U.S., you call an 800 number and answer questions. Most likely you will be told to go to an airport immigration office if you arrive in the southeastern U.S. If you are in the mid-Atlantic coast, you may get a personal visit at the boat for inspection. If you are in the northeast, then you probably will get a visit. If you are on the West Coast then you will probably have to take the boat to a customs dock. If your country offers cruising permits to U.S. boats, then you will probably be issued a cruising permit for U.S. waters.

There is also a requirement to report into customs via phone if a foreign flagged vessel changes port. The definition of “change ports” is pretty vague, so Customs and Boarder Patrol (CBP) bureaucratically clears it up with this statement: pleasure boats from foreign countries must obtain clearance before leaving a port or place in the U.S. and proceeding either to a foreign port or place or going to another port or place in the U.S.

For most cruisers who then dutifully call the 800 number when they move the boat, they are often greeted at the other end of the line by someone who doesn’t know a thing about the reporting requirement, nor do they care.

Many of the U.S.’s cousins aren’t much better. Australia’s entry procedures are known for efficiency and rules. Rules that add up to expensive check-ins with things like official termite inspections included. Remember that efficiency allows them to enforce fines, which they have been known to do, even for simple, unintended violations.

In any case, I always learn a lot about a country during my first clear in and wouldn’t want to miss it. You are often forced to use a little of the native language, you always interact with numerous local officials, you might take your first taxi ride in the country, and are exposed to kind strangers who will lend a hand, and most importantly, help you finish your Cruiser’s Scavenger Hunt on top.

Paul Lever and Chris Hunter have been cruising fulltime for the past four years. They’ve ranged from Seattle to Mexico, and Panama to Cape Bretton and Nova Scotia. Their Outbound 44 is currently in Curacao and heading back to Panama for another transit of the Canal. Follow their adventures at svjeorgia.blogspot.com.