Thoughts after using SSB and satellite phones over thousands of miles at sea (published August 2013)

The SSB radio is a time-honored staple of long distance communications aboard seagoing ships of all kinds. And for good reason, after the initial expense in hardware and a modest installation effort, the units typically offer years of reliable service with very little ongoing expense. Over the past decade though, we have seen the emergence of comparably affordable and reliable satellite phone technology.

With both of these technologies now at our fingertips, the big question asked by passagemaking sailors is, “What is it like to use one versus the other when and where it really matters?” In the interest of realistic data, I’ve taken two types of satellite phones and an SSB radio on two boats and three offshore passages totaling over 3000 nautical miles and I have come up with some fascinating results. Here is what I experienced, along with some useful information to know before you commit.

THE TECHNOLOGY

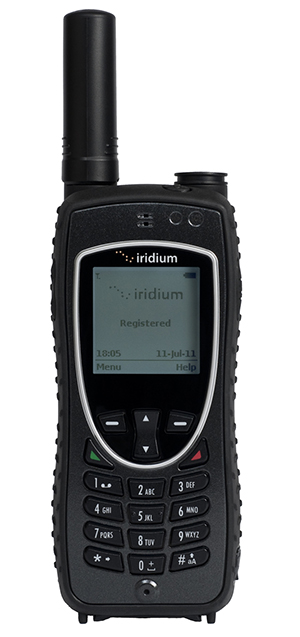

The Iridium 9575 Extreme satellite phone is the latest and greatest commercially available model from the popular and highly regarded Iridium network. It, and its older but more battle-tested sibling, the 9555, are used by commercial operators, private yachts and even extreme land-based expeditions to remote geographic locations. I chose the 9575 primarily because of its increased water resistance compared to the 9555, which allows for operation in more inclement weather while on deck. I kept the phone and related accessories sealed in a pelican case below deck when not in immediate use.

The Inmarsat iSatPhonePro is another semi-rugged handset marketed for use on the Inmarsat network. The two networks have some differences in their satellite positions and orbits, and this phone seemed more sensitive to pointing the antenna in the right direction, which I found was not always straight up.

For both satellite phones, if I was using them on deck for computer data I enclosed them and any attached cables in a ziploc plastic bag to protect from spray. This was not possible when making a voice call.

The SSB radio I used was the ICOM M802, equipped with the usual AT-140 tuner and a KISS-SSB radial ground plane. Unlike a satellite phone that incorporates the complete antenna and radio transmitter into the handheld module, the SSB radio system needs a much larger antenna and a very good grounding system. On a boat, this often means a lot of copper foil installed in the bilge, expensive copper grounding plates and other frustrating and wallet-draining approaches. In contrast, the KISS-SSB ground plane looks like a simple section of garden hose with a wire coming out of one end. You screw it to the antenna tuner and run the hose more or less straight out horizontally anywhere you can easily stow it. The tuner can take gentle bends and easily threads through the back of lockers and ventilation spaces, needing nothing more than the occasional wire tie to hold it in place.

Another slight complication of the SSB radio is that, if you want to use it for computer data such as weather or email you need to have a modem. The current and undisputed king of radio modems is the SCS corporation’s PACTOR line, and one of these little marvels will set you back about as much as the entire radio. Fortunately, as you’ll find out below, they are worth every penny. Just keep in mind that there are different “levels” of PACTOR models, numbered one through four with the relative data speed increasing with each model. The most common modems available and in use are the PACTOR two and three models. PACTOR four is the latest crop and is what I equipped on my test sailboat thanks to a loaner model, which I subsequently purchased from Farallon Systems in California.

All of the above systems were used in conjunction with my Apple Macbook and my crew’s Windows-based notebook computer. Both worked just fine.

GOING TO SEA

Armed with these technologies—Iridium and Inmarsat satellite phones and the SSB radio with PACTOR modem—I headed offshore across the Gulf of Mexico, into the Atlantic, and up the Eastern seaboard of the US to Nova Scotia, testing as I went.

The number one purpose for all of these devices was to obtain detailed weather information in the form of voice and text forecasts, GRIB files (for more on this, see David Burch’s column in the July, 2013 issue of BWS), and SMS/email updates from folks who were following our progress and doing some additional research on our behalf.

The second major use was for me to stay in contact with friends and family back home and to post updates to my website via email. I used the Sailmail system via SSB and the XGate software via Iridium to ensure that each service was using its most optimized form of email transfer.

It became apparent that for these data-heavy needs, the SSB radio was the most reliable, least expensive, and believe it or not, the easiest method. While the satellite phones and the SSB radio are both astoundingly slow compared to modern Internet data connections, the PACTOR P4Dragon modem with its higher overall speed and more reliable connections, consistently outperformed the Iridium 9575 in both connection reliability (the Iridium would drop the connection more frequently, particularly in a rolling sea or inclement weather) and in data speed.

In addition, without an external satellite antenna, my Iridium model would generally not find a network when below decks except occasionally when sitting in the companionway with the hatch open. Not everybody has this problem, but it was significant enough on two different older fiberglass boats that I sailed on for me to spend the money on an external antenna for my Iridium phone. The iSatPhonePro was equally troublesome in this regard and often took longer to simply acquire a signal (occasionally it took three to five minutes) than to dial up on the SSB and download my request from Sailmail.

Another issue I ran into with the Iridium phone in particular, was the lack of robustness of the external connectors. In order to connect a USB cable for computer data to the phone I had to clip on a flimsy plastic “coupler” or “dock” to the bottom of the phone. I found that the USB port and the pins that connected the data between the connector and the phone degraded rapidly in a maritime environment even though I had been exceptionally careful to avoid exposing the phone to spray. As a result, it became so difficult and frustrating to get a reliable data connection to my computer from the phone that it was effectively useless for email by the end of the voyage. I had to buy a new and rather expensive connector to restore this functionality.

The iSatPhonePro did not seem to suffer from this problem, but we didn’t use it for email at all; aside from having more expensive minutes on our chosen plan, ours often lost connection more frequently than the Iridium. The second sailboat I took on this passage was not equipped with the SSB and I sorely missed it when forced to use the Iridium for email and weather data.

The least common use for any of these technologies was for voice communications, either shoreside or ship-to-ship. My crew and I tend to prefer a more focused offshore experience without constant contact back home, so there was not a lot of opportunity to test the voice features. We did, however, use the free incoming SMS feature of the satellite phones so friends and family could send us short updates. This was a welcome feature, but replying was expensive so we avoided it and used the SSB at effectively zero cost.

For ship-to-ship voice communications, the SSB was more useful, although not in the manner you might expect. Most ships don’t leave their SSB radios on if they are even equipped. Much like a satellite phone, most conversations are prearranged. Times and frequencies are agreed upon and the call is effectively point-to-point, though the airtime is free with the SSB. However, the area in which the SSB really showed an advantage was in participating with radio networks, or “nets.” These are large area conversations with many ship and shore stations tuning in to the same radio frequency to share information, keep track of each other and pass messages back to shore.

In the Gulf of Mexico I often found myself corresponding on the Maritime Mobile Service Network with operators in Toronto, ships off the coast of New England, and if the atmosphere was right, even with operators on the other side of the Panamanian isthmus. In this case, the shoreside operators were volunteers who found information such as dockage or parts suppliers in an upcoming port, relayed messages by phone or email, and offered other forms of information and communication help as needed. This is an invaluable resource to mariners and I have heard of many serendipitous opportunities arise as a result of these nets. Some of these networks require a ham radio license to access, which I have, but many others operate on standard marine frequencies that are more specific to a locale such as the Caribbean.

While offshore, there was one important instance where the satellite phones played a useful and important role. While sailing to Bermuda from the Florida Keys the boat I was on suffered a dismasting. This took the SSB radio antenna down with it, and in the intervening time until I could rig a backup out of some scrap wire the satellite phone was my only long distance communications method. Fortunately in my case this was not a matter of life and death and I did not need to get an urgent message out, if I had been in such a situation and unable to rig an SSB antenna the satellite phone could have been much more important. Conversely though, it should be noted that in the recent HMS Bounty tragedy, it was the SSB radio that was able to put through the distress call via PACTOR and email.

FINAL THOUGHTS

During my blue water experience the SSB radio proved to be the most useful overall and when sailing on vessels with only satellite phones I found that I would rather have the SSB. That being the case, there were instances in which the satellite phone would have been the right tool for the job, such as voice calls back home. The satellite phones could more easily be brought to other boats as well. But these specific advantages came with some frustrating usage requirements, such as having to stand in exposed locations to use the gear. From an emergency standpoint, when my mast came down the only tool I had available for long range communications (until I rigged an emergency antenna) was the satellite phone, but in inclement weather the SSB was by far the more reliable.

The prudent sailor will consider all options and choose the method that suits their individual needs. If you have the option, carrying both modes of communication is probably the best. And if you do, I’d bet you find yourself spending more time enjoying the SSB than the satphone. I did.

When it comes to airtime costs, another consideration people often find themselves weighing is the price of a PACTOR modem versus purchasing satellite phone airtime. This is where doing the math for your expected use is essential, as the various combinations of initial fees, per-minute add-ons, and email service costs vary widely depending on cruising region, estimated daily use, and duration of cruise. Always overestimate the minutes you expect to use as dropouts and redials can cause significant overages in retrieving your data via satellite networks, especially if you haven’t purchased the external antenna and internal cradle and rely on manually keeping the handset’s internal antenna properly oriented.

Another major question I get asked is whether or not the new PACTOR 4 protocol is worth the extra money. I have to say yes, it is. It connects faster, offers more reliable connections, (even when connecting to a remote station which only uses Pactor III) which translates to fewer redials and generally makes using the SSB less frustrating than previous modes of PACTOR. Best of all, there are new lower-cost P4 modems available which put the purchase price at about the former used price of a high-end PIII model, making the decision easier.

Other than the PACTOR modem, which at the time of the sea trials was on loan, all devices and airtime costs were out of either my crew’s personal funds or mine and no company sponsored or subsidized our tests. I subsequently purchased the PACTOR modem myself before writing this article.

I have not heard many complaints about the issue I had with the Iridium connector module and the Iridium 9555 model has an excellent reputation for reliability, so I would expect that my connector may have been defective. In terms of avoiding exposure during use, many sailors I know of who carry a satellite phone have equipped an external antenna along with a below-decks docking station or cradle for the phone. When these options are added to the initial phone cost the total price can exceed a fully equipped SSB/PACTOR station, even before any airtime minutes are purchased. Thus, I consider the two options roughly equal in installation and acquisition cost for a comparable and well-protected setup, with the satellite phones significantly more expensive in ongoing operating cost.