The Transat Race is the classic singlehanded offshore event that started it all (published June/July 2016)

It began as a bet and over the course of almost five decades has grown to become the granddaddy of all offshore ocean races. I am talking about the OSTAR, or as it is now named, The Transat bakerly.

In 1960, a handful of British sailors made a wager to see if they could sail singlehanded across the Atlantic from England to the United States and who could do it the fastest. Among them were Francis Chichester and Blondie Hasler. Both were pioneers in offshore sailing and they were the driving force behind this new event that was roundly being ridiculed and criticized as foolhardy. But they were determined sailors and with sponsorship from the Observer newspaper the Observer Single-Handed Trans-Atlantic Race, or OSTAR, was born. The idea first floated by Chichester and Hasler became the blueprint for one of the most successful ocean races ever.

Over the years, the real success of the OSTAR came from the numerous characters, some famous and some infamous, who took part as the idea of solo sailing caught on and technology changed to attract bigger and faster boats. Chichester and Hasler were no slouches when it came to being larger than life characters, but it was really the indomitable French sailor Eric Tabarly who put the race on the map.

THE EARLY LEGENDS

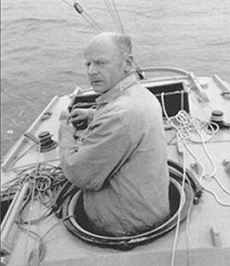

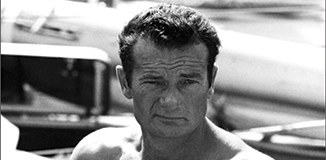

Chichester won the first race in a time of 40 days, 12 hours and 30 minutes, but four years later Tabarly showed up and whacked close to two weeks off that time. His boat, Pen Duick II, was the biggest boat in the fleet and was sleek and lightweight when compared to the other entries. Tabarly had devised a method whereby he could remain below decks and check on things by looking out through a Plexiglass bubble mounted on the deck while his innovative windvane steered the boat. But the windvane only worked for the first few days so he had to hand steer most of the way across the Atlantic. This story, coupled with Tabarly’s rugged good looks and charm, turned him into an instant hero among the French public and on his return to France President de Gaulle awarded him the Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur— the Legion of Honor, France’s highest civilian award.

Tabarly would return a number of times to compete in the OSTAR and changed the game entirely in 1968 by entering the first multihull. However, things did not go well for him after he collided with an anchored ship on the second day out. He was forced to return to port to repair his boat but the repairs proved to be inadequate and he eventually retired. He won the brutal 1976 race and finished 3rd in 1984, the last time he would compete in the event. The impact that Tabarly had on the early days of the OSTAR was huge and he not only brought innovation to the race, he inspired generations of French sailors to follow in his wake.

There were other larger-than-life sailors who competed in the early races, including Tabarly’s crewman Alain Colas who bought Tabarly’s trimaran and won the 1972 race in it. By this time the race officials were starting to impose some rules in an effort to make the race safer; one of these was to set a minimum boat size to be eligible to compete. They did not impose a maximum size and Colas returned four years later with a gigantic monohull, Club Méditerranée, which measured in at a whopping 236 feet.

Most people were astounded at the idea that one man could sail a boat that large, but Colas made it across finish line second behind none other than Eric Tabarly. A couple of years later Colas was lost at sea as was Tabarly who was swept overboard from his boat in the Irish Sea in 1998.

MOXIE AND THE FRENCH

By this time, the event was being completely dominated by French sailors who dubbed the race La Transat Anglaise or The English Transat. It was, however, the American sailor Phil Weld who won in 1980. Weld was a self-made man who owned a number of newspapers north of Boston and had commissioned Dick Newick to design a custom 56-foot trimaran which he named Moxie. The length of the boat was right up against the new upper size limit of 56 feet that had been instituted in 1980. This was Weld’s second OSTAR and because of his advanced age no one thought that he had much of a chance to win. But, he not only won the race, he knocked three days off the record time that had been set by Alain Colas.

In 1984, the charismatic French sailor Philippe Poupon entered with his boat Fleury Michon. He was first to finish and was giving his victory press conference when he got some bad news. Earlier in the race, the pre-race favorite Philippe Jeantot had capsized and fellow sailor Yvon Fauconnier diverted to assist him. The race organizers awarded Fauconnier 16 hours for the time he had lost helping Jeantot and that was enough to give him overall victory. Upon hearing the news, Poupon promptly burst into tears.

Poupon returned four years later to avenge his loss and ended up not only winning the 1988 race but setting a new course record of 10 days, 9 hours and 15 minutes. He had crossed the Atlantic four times faster than Chichester had almost three decades earlier. Poupon’s victory was a little overshadowed by an extraordinary thing that happened to fellow competitor David Sellings. Sellings found himself surrounded by a pod of 50 or more whales that followed him for three days before eventually attacking his boat and sinking it. Sellings was only able to grab a few belongings before jumping in his liferaft. He was later rescued by a German freighter and stated that “it was terrifying.”

EUROPE 1 STAR

The event was growing steadily and along with it the budget to run the race. After a successful three plus decades as title sponsor, the Observer newspaper pulled out, a new sponsor was found, and the race was renamed the Europe 1 STAR.

To understand the attraction of the race you have to understand the course. It’s almost all upwind as the boats have to slog into steady westerly headwinds day after day. In the early races, no outside weather forecasts or routing information were allowed. But, by the early 1990s, competitors could get weather information from their shore based advisors that allowed them to follow routes that avoided lengthy upwind legs. The race had become not only one that attracted some of the toughest and sea hardened sailors, but also a new generation of sailors who knew how to use modern technology to get an edge.

In 1992, there were new faces in the race, sailors who would later become household names in France. Loïck Peyron would go on to win the race but he had stiff competition from not only Poupon, who was forced to retire, and the upcoming French sailing star Florence Arthaud, who capsized off Newfoundland, but also from Francis Joyon, Paul Vatine and Laurent Bourgnon. Peyron would win again four years later.

The 2000 event was dubbed the ‘Ellen Era’ as Ellen MacArthur stepped onto the scene and forever changed the way we view female sailors. At 23, the British lass was one of the youngest competitors in the race and she was competing against some of the best and most seasoned men in offshore sailing—Thomas Coville, Michel Desjoyeaux, Yves Parlier, Mike Golding, Roland Jourdain and Dominique Wavre.

The fleet was split in two with separate monohull and multihull classes, but all eyes were on the Open 60 division as many competitors were using the race as a shakedown for the upcoming Vendée Globe singlehanded around the world race. No one expected MacArthur to shine, but shine she did. On the ninth day of the race she spotted a lull in the weather ahead and took an unfavorable tack to the north to sidestep it. In doing so she put 75 miles between her boat and the nearest competition and was able to hold that lead until the finish. It was one of the most extraordinary wins in an event that has had more than its fair share of extraordinary wins.

THE TRANSAT

In 2004 the OSTAR became The Transat. The event had outgrown the original race organizers, the Royal Western Yacht Club, and it was time for some professional race management. Mark Turner and his OC Group stepped in and, at great risk to their company, took over the race. By now there were three divisions; multihulls, Open 60 monohulls and 50-foot monohulls; for the 2004 event, 40 boats showed up on the starting line.

A week into the race the fleet was decimated by a severe front. Jean-Pierre Dick on Virbac was rolled 360 degrees and dismasted in 50-knot winds while Vincent Riou’s PRB lost her rig and Bernard Stamm was forced to abandon his boat Cheminées Poujoulat-Armor Lux after it lost its keel and capsized. The storm triggered a series of extraordinary rescue operations but there was no loss of life and Stamm eventually returned to his stricken yacht and successfully salvaged it. In a tight finish, Michel Desjoyeaux aboard Geant narrowly beat Tomas Coville on Sodebo in a new course record time of eight days, eight hours and 29 minutes.

In 2008 The Transat became the Artemis Transat and a new class of 40 foot boats was added. As usual, the North Atlantic dished up its usual summer sailing conditions of gale force winds, which forced a number of top skippers to retire. Vincent Riou abandoned his boat after he struck a basking shark and damaged his keel. With a huge storm approaching, he did not feel safe aboard his damaged boat and was picked up by Loïck Peyron who went on to win the race. It was to be the last running of the race for a while. Mark Turner and the OC Group placed the race on ice, so to speak, while offshore ocean racing sorted itself out. The big multihulls were no more, IMOCA, the group that runs the Open 60 class, was dealing with internal issues and there were scheduling conflicts with other events.

Eight years after the last running of The Transat the event is back and looks to be stronger than ever. On May 2, over 20 boats once again set sail from Plymouth, this time bound for a brand new yet-to-be-opened marina in New York City. The ONEº15 Brooklyn Marina is a new facility that has the skyline of Manhattan as a backdrop. For the first time since Alain Colas entered in Club Méditerranée there will be a return of some big boats with the Ultime Class open to multihulls in excess of a 100-feet. Vendée Globe winner François Gabart will be there on his new Macif, Thomas Coville will compete on Sodebo and Yves le Blevec will race his huge trimaran Team Actual. There is a good showing in the IMOCA 60 class with Armel le Cléac’h and Jean-Pierre Dick the pre-race favorites, while the most intense racing will be among the Class 40s with 12 boats competing.

Like all the previous races, this one will be a long upwind slog, but the sailors will know that they are sailing in the wake of a rich and interesting history of one of the most challenging and rewarding ocean races. There is however, just one sailor who will immerse himself in the experience and that is the legendary Loïck Peyron who will race aboard the original Pen Duick II. This will be his 50th transatlantic crossing and he plans to do it just as Tabarly did it all those years ago; with a sextant and with a healthy spirit of adventure in his heart.

Brian Hancock is a sail maker and veteran of many offshore and round the world races. He lives in Marblehead, Mass.