The leaves turn color and drop. The Canada Geese head south. The warm allure of the tropics beckons. But getting there may or may not be so alluring. (published October 2013)

The days are getting shorter. The cooler air foretells of a shift, not only in the weather, but also the fact that it’s time to shift serious cruising further to the south, whether that’s somewhere in the Caribbean, Mexico or elsewhere. Insurance companies may not want vessels too far south too soon and have mandated November 1st as the end of hurricane season. But, the hard reality is that November or December deliveries out of North America aren’t a piece of cake on either coast. Leave too soon, and you risk the wrath of the insurance companies. Leave too late, or on a bad weather pattern, and you risk the wrath of the weather gods.

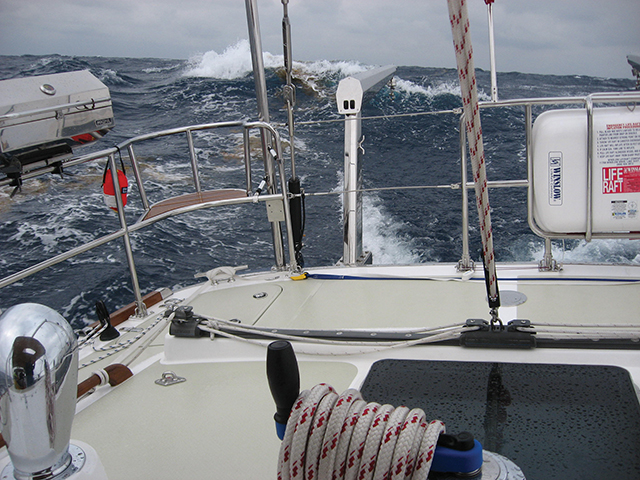

Moving south in the fall places skippers between the proverbial rock and a hard place. Hurricanes are relatively small but extremely dangerous “rocks” upon which no one wants to fall, but they can often be circumvented. Fall’s extra-tropical low pressure systems, huge by comparison but packing wind speeds that may “only” reach 35 to 60 knots can still wreak havoc among the fleet heading south. Getting caught in the Gulf Stream in a November cold front quickly becomes a hard place no one enjoys. There is hope, however, and that hope lies in preparation and understanding the weather into which you’re about to embark.

PREPARATION

The fact is, it really doesn’t matter whether you’re preparing for a late fall passage down the East Coast of the U.S., heading to Mexico from the West Coast or Pacific Northwest, making for the Caribbean or just taking a long cruise, getting your preparation wrong can add to the risk and almost certainly will diminish the enjoyment of the trip. Happily enough, most people have sufficient time to prepare for a passage. Regardless of the amount of time necessary, though, the bare bones of preparation remains much the same for everyone, and that preparation begins with lists.

Generally, I tend to break tasks down into various departments: nav area, sails, deck hardware, mechanical, provisioning, safety, etc. I have a generic list of tasks that should be addressed prior to departure, and a pretty complete list of tools that I would want for long passages. Neither list is totally complete, but they provide a good start in the thought process. Some things on the lists apply to a particular boat or passage, and some things don’t apply. Together, they provide a good starting point from which to build an accurate list that will help us get a boat from Point A to Point B, anywhere on the planet.

Once offshore, we know there aren’t any hardware stores, chandleries, sail lofts or machine shops. We’re on our own. So, we’ll have to make do with whatever we have with us or learn to do without it. We’ll have to fix it or forget using it once something is broken. And things do break. Spinnakers blow out, engine filters need to be replaced, hose connections leak, winches start to rattle and lines chafe. You will try your best to take care of most of those things prior to departure. You’ll check lines while underway. You’ll take care to reef early and often. But problems will occur anyway and the thoroughness of your preparations will determine how successful you are in overcoming those problems.

While having a very complete list of tasks, tools and repair kits is a good start, you will need to prioritize which items fit into one of several categories. Which things do you “Need To Do/Have”, “Would Like to Do/Have”, “Can Easily be Deferred”. You may want to add an extra 50 feet of chain to the 200 feet you already have, but if you’re cruising in shallow water this year, you may be able to defer that to a later date. Similarly, having all of the tools to complete all of the tasks that you’re likely to encounter can be convenient, but if you’re sailing short distances between well-serviced ports, you may be able to reduce your tool inventory and use your resources elsewhere.

Some jobs may be best left to the boatyard to perform, such as a major engine overhaul or replacing the standing rigging. The owner or skipper should go through the work list, determine which jobs are to be done “in-house” by the crew, which are to be done by the yard, and which are to be performed by outside contractors. The cost for each job is estimated, priorities are established and the list is confirmed. After deciding on the final work list, the work can be appropriately delegated and begun in a suitable schedule. It’s worth understanding that everything usually takes longer than you originally thought it would. And you want to start early so you leave yourself ample time to select a suitable weather window in which to depart.

WEATHER WINDOWS

It’s a common axiom with hikers that most accidents are caused by people who are attempting to adhere to a rigid schedule. “I have to get back to the office on Monday, so we’re leaving today!” If “today” happens to foretell flash floods or many feet of snow, the hikers in question may be better advised to either scrap their plans or let the office wait. The same is true of sailors, determined to get to some island by a certain date while running on a tight schedule. Paying attention to the vagaries of the weather is often a higher priority than paying attention to a scheduling calendar. If you need to be somewhere by a particular date, leave ample time for delays in departure. And then allow more time again. You may be able to make good time towards your destination, but you may not, and when confronting fall weather patterns, you always want to allow yourself options.

During the summer months, cold fronts often impact the West Coast or move off the East Coast about every six to seven days. It’s not a frequency that’s cast in stone, but it is an approximation that illustrates how weather-related things change with the changing seasons. During the fall and winter, in the mid-latitudes, cold fronts increase in severity and frequency, passing about every three or four days. So, when it is time to head south, you will have weather windows of four days at best.

Leaving from ports in the Northeast, it takes about a day and a half to three days to get to the warm Gulf Steam. From the Chesapeake, you will be across the Stream in 24 hours which is why rallies like the Salty Dawg Rally have chosen to start from Hampton, Virginia.

From the Northwest, you don’t have the tricky Gulf Stream to deal with, but you do have to watch out for fronts coming across the North Pacific every four days or so. It is usually best to stage southward during the fall to San Diego and then make the jump to Mexico and beyond at the end of hurricane season. You could even join up with the crowds in the Baja Ha Ha.

As cold fronts approach, they bring cold northerly winds, sometimes very cold during the fall and winter months. When those cold northerly winds pass over warm water, the cold, dense air descends, adding significantly to the surface wind speeds. When wind is pitched against a current, such as the Stream, it creates huge, steep, breaking seas. Timing your departure from the Northeast, in particular, when heading to Bermuda and the Caribbean is a vitally important consideration. Plunging through the Gulf Stream in a cold November northerly is placing you and your vessel squarely in that hard place you don’t want to be. You should allow enough time to safely get well south of the Gulf Stream prior to a northerly setting in during the fall and winter. To do otherwise places you and your crew at risk. It makes sense to use the services of professional weather gurus and routers to help you pick the safest weather windows and routes. Chris Parker at Caribwx and the pros at Commanders Weather are both highly respected and easy to work with.

Moving south as winter prepares to descend on North America can be a beautiful and gratifying experience as day by day, the weather gradually warms and the winds favor sailing. Offshore, watches begin to melt one into another as the clouds form fair weather cumulus cotton balls overhead. That serenity is not a foregone conclusion at any time of the year, however, and it is certainly not a given in the fall or early winter. Preparations must be thorough and weather awareness must be consistent. And with good planning and appropriate actions, you’ll be enjoying the sunnier, warmer climes soon enough.

Moving south as winter prepares to descend on North America can be a beautiful and gratifying experience as day by day, the weather gradually warms and the winds favor sailing. Offshore, watches begin to melt one into another as the clouds form fair weather cumulus cotton balls overhead. That serenity is not a foregone conclusion at any time of the year, however, and it is certainly not a given in the fall or early winter. Preparations must be thorough and weather awareness must be consistent. And with good planning and appropriate actions, you’ll be enjoying the sunnier, warmer climes soon enough.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net.