Two of the world’s most experienced offshore sailors and dedicated seamanship educators, share what they have learned over lifetimes at sea (with John Neal and Amanda Swan Neal, published June/July 2017)

Having spent most of our lifetimes sailing and teaching ocean passagemaking, we enjoy following those new to sailing as they start mastering skills and assuming responsibility for their own safety. To a sailor, this comes under the broad term of seamanship. We’ve come to understand that seamanship is gained from many sources and only partially by reading books and taking classes. It’s often repeated practical experience combined with basic common sense, preparation, awareness and respect for one’s surrounding environment that makes for good seamanship.

Seamanship is one of the keys to your safety and enjoyment of your sailing experiences whether you’re going out on a day sail or on an around the world cruise. It applies to all vessels and their crew and poor seamanship or judgment can result in damage to your vessel and injury to your crew. In this article we’ve separated seamanship into two categories, pre-departure: how you prepare your boat, yourself and your crew; and seamanship at sea: tips and advice in dealing with a wide range of conditions.

BEFORE DEPARTRURE

Becoming an accomplished sailor takes knowledge and practice but there are a number of skills you can study before you go sailing. Take the time to learn the terminology not only of the yacht’s parts but also the sailing commands, realizing that sailing’s unique and specific language varies from boat types and skippers. Therefore, study the terminology for the type of yacht you will be sailing and ensure that you understand and can execute the commands given to you by captain and crew. When an onboard situation becomes stressful, there may not be time for someone to explain what they require you to do. There should be no need for shouting, which may result when a person is unsure or unable to explain what is happening or needs to be done.

Two concerns that frequently affect new sailors are heeling or falling in the water. Gaining an understanding of yacht design, understanding why vessels heel and what you can do to reduce heeling frequently helps reduce anxiety. A competent swimmer comfortable in the water will always have less anxiety than those who are not strong swimmers. Whether in tropical or temperate climates, we swim at most opportunities incorporating long swims as part of our personal fitness program. We both enjoy maintaining our underwater skills and this has proven useful for clearing lines around the prop, dealing with failed ball valves and cleaning the antifouling and prop.

A sailor who knows their location is one who is more at ease with her surroundings. Complete a coastal navigation course and become proficient at navigation so that you can quickly and accurately plot positions on paper charts. Practice using radar and AIS. Starpath Radar Trainer is an excellent computer instructional program. If your MFD/radar is an older unit not AIS-compatible, consider adding a separate, stand-alone AIS transceiver such as Vesper Marine’s Watchmate. Another more expensive option is to install a new integrated MFD (multi-function display) combining radar, chartplotter and AIS. If you’re planning extended voyages, you’ll certainly appreciate the fact that that newer systems draw considerably less power and are fully integrated and easy to operate.

Establish and review emergency procedures for crew overboard, fire, sinking, abandon ship, rig and steering failure, first aid, communications and tsunami response. A crew that has an understanding of these procedures is one that is well prepared.

Post a Sail Reduction Guide so everyone knows the correct sail combination for specific wind speeds. Having reliable wind speed and direction instruments takes the guesswork out of determining appropriate sail combinations. Ensure that everyone understands how the sails are handled, including reefing and safe winch procedure. Can the main be reefed in under three minutes? If heading offshore, gain an understanding of storm management tactics and if possible, formulate a plan. Practice the deployment of storm tactics and devices.

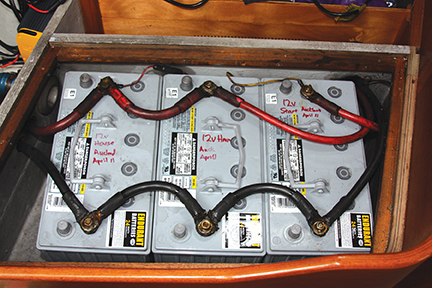

Don’t overload your boat as that makes it slower and more vulnerable to damage from breaking seas. Establish dedicated safe stowage procedures both above and below decks. Evaluate and eliminate items on deck and below to keep your boat free of clutter that might become airborne during storm conditions or slip down into the bilge and block the bilge pump. Prepare your vessel for a knockdown or for a large wave dumping into the cockpit; you may need to add a pin or strap to secure companionway wash/drop boards. Ensure that batteries, floorboards, locker doors and drawers are substantially secured.

Keeping your crew hydrated and fed is important not only for morale but it turns into a seamanship issue in heavy weather. A crew that is not well nourished or properly hydrated will sooner suffer from fatigue, which often leads to poor judgment. Provision with meals that are easily prepared by anyone aboard and include some freeze dried meals and healthy, high-energy snacks such as trail mix, granola bars, instant porridge and soup, dried fruit and nuts. A top plunger Thermos strapped into a corner of our galley counter saves us having to boil the kettle each time we’d like a hot drink or instant meal. If a boat has skanky-tasting tank water, plan on thoroughly cleaning the tank and consider installing a quality water filter to purify your drinking water.

Keeping your crew hydrated and fed is important not only for morale but it turns into a seamanship issue in heavy weather. A crew that is not well nourished or properly hydrated will sooner suffer from fatigue, which often leads to poor judgment. Provision with meals that are easily prepared by anyone aboard and include some freeze dried meals and healthy, high-energy snacks such as trail mix, granola bars, instant porridge and soup, dried fruit and nuts. A top plunger Thermos strapped into a corner of our galley counter saves us having to boil the kettle each time we’d like a hot drink or instant meal. If a boat has skanky-tasting tank water, plan on thoroughly cleaning the tank and consider installing a quality water filter to purify your drinking water.

Nothing affects your safety and comfort on the water more than weather. Learn the dynamics of weather patterns by ideally taking a marine weather course, or at least studying Chris Tibbs’ RYA On-Board Weather Handbook. Get in the habit of checking the weather daily, whether via internet, on the television, in the newspaper or on the VHF. Have a method for getting weather updates at sea. A simple no-cost resource we use daily worldwide are GRIB (gridded bianary files) forecasts from www.saildocs.com received over an Iridium satphone. Occasionally, requesting a detailed text forecast from a private weather router such as www.commandersweather.com or www.wriwx.com can prove invaluable, particularly in an area of dynamic and volatile weather conditions such as crossing the Gulf Stream or Bay of Biscay.

When undertaking a passage with two people where there is an increased chance of rough conditions, consider taking an experienced third crew person. An extra watch person greatly decreases your chance of sleep deprivation (three hours on watch and six off instead of three on, three off). This may also be a requirement of your insurance company, particularly on your first offshore passage.

AT SEA

Basic seamanship follows protocols and rules born from tradition. Competency, organization and prudent decision making along with a continual awareness of safety generally creates a happy ship with minimal drama. Often an errant event can snowball into something more serious so trial and error may not be the best method of learning for the beginning sailor. Slowly build your skills realizing that everyone learns differently; for example, some people are tactile learners, learning by repetition while others are conceptual learners, learning easily by studying diagrams or instructions.

Establish a watch schedule. Many cruising couples alternate three hour watches at night and sharing watches during daylight hours. Standing watch in a sheltered location in the cockpit rather than below increases overall situational awareness. Hourly log entries with position, course, speed, log, wind speed and direction and barometric pressure are an important part of watch duties along with plotting your position on a paper chart at least every four to six hours. Don’t rely solely on electronic charts as some reefs and rocks may not be displayed.

Avoid seasickness and keep everyone involved with shipboard life. Try to maintain a civilized routine,  even in rough weather, with set mealtimes together. Maintain hydration and encourage crew to keep the boat clean and tidy; we even post a duty rooster. Monitor battery voltage, charging when necessary and inspect rigging and sails daily for signs of wear or anything amiss. Consider checking in with a radio/weather net with your daily position report. This often relives anxiety for those new to passage making.

even in rough weather, with set mealtimes together. Maintain hydration and encourage crew to keep the boat clean and tidy; we even post a duty rooster. Monitor battery voltage, charging when necessary and inspect rigging and sails daily for signs of wear or anything amiss. Consider checking in with a radio/weather net with your daily position report. This often relives anxiety for those new to passage making.

Ensure that everyone understands the watch instructions and have them written in the log book. Maintain leadership, responsibility and open communication. Encouraging communication of problems promptly is an excellent way of avoid misunderstandings.

Once settled in on passage, practice all points of sail, reefing, heaving-to, rigging a preventer and if appropriate the setting of light air sails and storm sails. Practice single-handling the boat (with crew staying below) and Lifesling man-overboard retrieval.

Sail your boat to the conditions. Modern sailboats sail best at moderate angles of heel, not with the rail under water due to the boat being over canvassed. Caution should be taken with multihulls to not over stress the rig or sails. This is frequently a problem for inexperienced sailors and it pays to be conservative until you understand how much speed your crew and boat can handle. The best time to reef or reduce sail is when you first think about it as waiting to see if conditions worsen increases strain on the crew and equipment. We often discover that after reducing sail, when it was borderline whether or not an additional reef was required, boat speed remains the same, leeway is reduced and the comfort level increases.

The following topics contain notes on conduct and seamanship in certain situations.

COLLISION AVOIDANCE

Modern ships may travel at speeds up to 25 knots so the time from first sighting a ship until potential collision may be under 10 minutes. Rule Five of the International Regulations for preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS) makes maintaining a watch a matter of law. This rule applies in any condition of visibility, and states, “Every vessel shall at all times maintain a proper lookout by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and the risk of collision.”

The COLREGS clearly creates an obligation to maintain a continuous visual and audible watch for signs of other vessels and to use equipment such as radar and AIS to supplement those senses when the situation requires.

AIS (Automatic Identification System) is an excellent collision avoidance tool, but is not required for fishing vessels. We’ve noticed that in the Pacific not all vessels required to be transmitting AIS signals are doing so. In the Atlantic and Europe, it’s rare to encounter any vessel including yachts that are not transmitting AIS signals.

Never assume that a ship you sight has someone on watch or can see your vessel. Never assume that a ship can quickly alter course or stop, because they can’t. Never attempt to cross in front of a commercial vessel. It’s safer to make an easily visible major course change, passing astern of a ship. Don’t cross close astern of a fishing or towed vessel.

Never assume that a ship you sight has someone on watch or can see your vessel. Never assume that a ship can quickly alter course or stop, because they can’t. Never attempt to cross in front of a commercial vessel. It’s safer to make an easily visible major course change, passing astern of a ship. Don’t cross close astern of a fishing or towed vessel.

Be prepared to quickly take evasive action if a ship alters course towards you. While on passage, if you judge your course will take you within two miles of a ship in clear daylight weather, or within 2 to 4 miles at night or with reduced visibility, attempt to contact them on Channel 16, explaining your intentions. Keep radio communications short. Speak clearly and slowly, using single digits for positions and courses especially when advising vessels of your intentions or course change. In international waters, English is rarely the watch keeper’s first language. Example: “Motor Vessel Silver Star, Silver Star, this is the sailing vessel Windsong, four point five miles on your starboard bow. Our position is … and I am slowing down so that you will pass ahead of me. Please reply on Channel 16”.

Broadcast Securité (see-cure-eh-tay) messages if sailing in heavy squalls with reduced visibility or if you are hove-to and have reduced maneuvering ability.

Monitor your radar and AIS continuously whenever you are within 100 miles of land or are experiencing reduced visibility. At night, when more than 100 miles offshore, turn the radar and AIS on for two minutes every hour to check for ships, squalls and land. The power consumption when doing this is negligible.

A masthead tricolor running light ensures maximum visibility and cannot be blocked by headsails or heeling and is essential to good seamanship when night sailing.

SQUALL AVOIDANCE

Several times in the tropics, we’ve experienced wind speed increasing from 12 knots to 60 knots in five minutes. Our most intense tropical squall occurred between New Zealand and Tahiti; the wind went from 5 knots to 80 knots and back to 5 knots in less than one hour. We saw the squall line approaching, dropped all sail and steered downwind in flat seas.

Keep a watch for squalls. If no one is on watch and you get hit by a squall you may discover your boat becomes quickly overpowered thus making it difficult to reduce sail. At night, squalls are generally visible as a dark cloud formation and on the radar usually display as a distinct mass.

Keep a watch for squalls. If no one is on watch and you get hit by a squall you may discover your boat becomes quickly overpowered thus making it difficult to reduce sail. At night, squalls are generally visible as a dark cloud formation and on the radar usually display as a distinct mass.

When you see a small squall approaching it’s wise to change course and avoid it if possible. If you can’t avoid a squall be prepared to quickly reduce sail. When about to encounter a powerful squall line or frontal passage, one frequently sees lightning at the leading edge and may possibly experience a blast of cold, damp air before wind speed increases. To lessen your exposure to these systems, reduce or drop sail and motor directly towards the area of least activity using radar as a tool.

SEAMANSHIP AT LANDFALL

Every year we hear of yachts becoming total losses after piling onto offshore reefs or islands. Don’t let this happen to you. Ensure that you are well rested for landfall. If you are fatigued from a difficult passage, the strong urge to get into port can overpower good seamanship and judgment.

Continually calculate your arrival time to ensure a daylight arrival. Be prepared to slow down or possibly heave to. Be patient. Don’t be tempted to make landfall in an unfamiliar port in the dark, squally, foggy or stormy weather as far more boats are lost while making landfall during these situations than are lost mid-ocean.

Electronic navigation charting systems don’t allow for safe landfall at night as few of the charts in third world waters have been corrected using satellite imagery. Maintain a watch with a good 360-degree lookout, remembering to check astern for overtaking traffic and monitor all electronic equipment: radar, depth sounder, GPS, and radio. Check current and tide tables and study the cruising and pilot guides. Expect the surface current to increase as you approach land.

SEAMANSHIP AT ANCHOR

Seamanship doesn’t end once your anchor is down. Make a practice of always plotting your GPS position on a paper chart as soon as you drop anchor in a new bay. This is a quick and simple way to check chart accuracy.

Ensure you always have an “out” if the anchorage conditions change. It’s prudent to set a course and enter waypoints to an alternative anchorage in event of a major wind shift. If possible, dive to check the set of the anchor.

If the wind should increase substantially or change direction, put out to sea, move to a more protected anchorage or set additional anchors. Don’t wait to see what other skippers do. Monitor the position of surrounding vessels as they may prove to be your highest risk.

If you’re safely anchored and an arriving vessel anchors directly upwind of you or in a way that blocks you from raising your anchor or you don’t feel comfortable don’t hesitate to either re anchor in another spot or ask the new arrivals to move. After you’ve had a few boats drag down on you during a midnight squall you’ll understand that this affects the safety of both vessels.

If you’re safely anchored and an arriving vessel anchors directly upwind of you or in a way that blocks you from raising your anchor or you don’t feel comfortable don’t hesitate to either re anchor in another spot or ask the new arrivals to move. After you’ve had a few boats drag down on you during a midnight squall you’ll understand that this affects the safety of both vessels.

Sailors can be like sheep, exhibiting strong herd instincts. If there is only one vessel anchored in a bay, an arriving skipper may anchor as close as possible to them. Don’t be guilty of this; perhaps the crew of the original vessel enjoys their privacy.

Gaining seamanship skills should be viewed as an ongoing process. Continually look for ways to increase your knowledge and practical application of shipboard tasks and procedures. Ensure your vessel is well maintained and always have consideration for the comfort and safety of all aboard.

John & Amanda’s current boat, Mahina Tiare III is a Hallberg-Rassy 46 which they have sailed 198,280 miles since launching in 1997. They update their website, www.mahina.com by satellite from around the world.

RESOURCES

On-Board Weather Handbook, Chris Tibbs, International Marine

Understanding Weatherfax, Mike Harris, Sheridan House

Illustrated Navigation, Ivar Dedekam, Fernhurst Books

Offshore Cruising Companion, John and Amanda Neal, www.mahina.com

World Cruising Routes, Jimmy Cornell

Surviving the Storm, Steve Dashew. www.Setsail.com

Radar Trainer, www.starpath.com

Heavy Weather Cruising, Tom Cunliffe, Fernhurst Books

Black Wave, John and Jean Silverwood, Random House

Ten Degrees of Reckoning, Hester Rumberg, Penguin Books