It was 1958 when the Florman family sailed from Florida to Cuba and then Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In Part One, in March BWS, they visited Cuba just as the revolution was starting (published April 2018)

Our crossing of the 50-mile-wide Windward Passage between Cuba and Hispaniola provided us with our next overnight sail. The passage proved uneventful as we put into a place in northern Haiti called Môle Saint-Nicolas, a well sheltered harbor inside of a cape on the northeast end of the island.

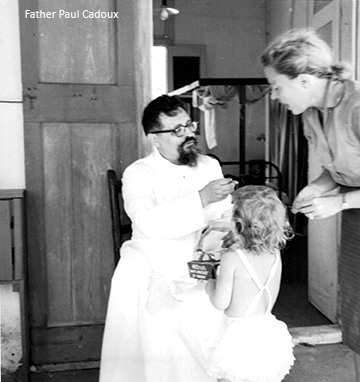

It was there that we met a French Missionary priest, Father Paul Cadoux, who was delighted to meet and host us. Mom and Dad both spoke French, Dad having been partially raised in Paris as a boy, so we were able to communicate easily. Father Paul shared with us that he felt he had the “Most unusual parish in the world”, because his parishioners would come to Catholic mass on Sunday morning and then in the evening would steal across the bay and practice voodoo by the light of fires up in the hills! This impressive man of the cloth had been a missionary in Haiti for 25 years and was the only white man around for 150 miles. He was also quite resourceful as he actually helped us resolve a continuation of our electrical problems we had first worked on in Cuba.

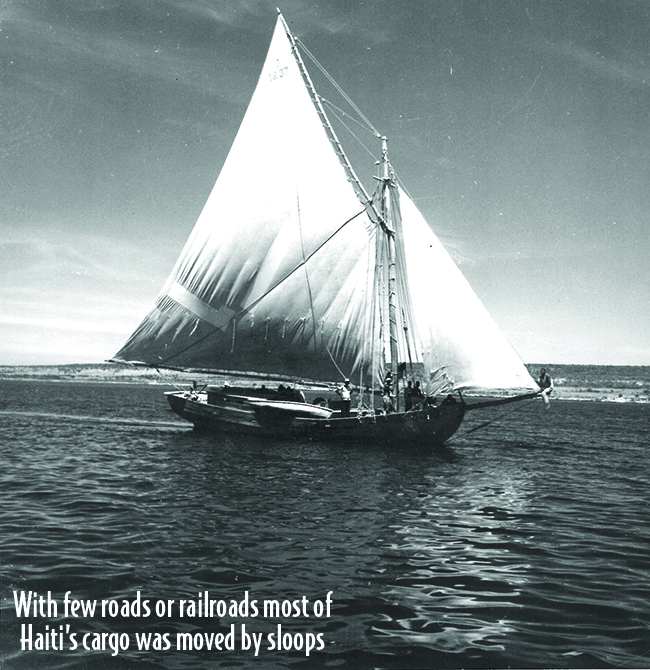

Sailing from Môle Saint-Nicolas down the Gulf of Gonâve also proved uneventful, but little did we know of the unpleasant surprises and challenging experiences that awaited us before we reached the capital of Port-au-Prince! Something we did not know before sailing to Haiti, was that a few months before our arrival, three Haitian men and five mercenaries from Miami had sailed there in a white two-masted sailboat of a size similar to ours, and had come very close to deposing the regime of the brutal dictator Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier.

So, even though we were an innocent family of five sailing the Caribbean, the Haitian authorities were very leery of the crew of another white, two-masted sailboat that was also home ported in Miami! What happened next, was our first indication of this problem.

We were putting into a bay called Montrouis, which is about half way between Môle Saint-Nicolas and Port-au-Prince. This turned out to be the same place where the eight men of the would-be revolutionary force had abandoned their vessel and commandeered a Haitian army jeep killing a number of Haitian army soldiers as they went; they made their way to the main garrison of Dessalines in Port-Au-Prince where they hoped to mount their coup d’etat.

These desperate would-be revolutionaries holed up in the garrison while plotting their next move. No one, including Duvalier, who was getting ready to flee the country knew how many rebels were in the invading force. But then the rebels sent out a young Haitian soldier to buy cigarettes. The soldier let his superiors know how few of the invaders there were and that proved to be their downfall. They were captured, tortured and sumarily executed.

“Dad, that man on the shore has a gun!” shouted my older brother Nils. We realized on our approach to anchor in Montrouis Bay that a man was shooting over our heads and shouting in Creole, all the while crouching fearfully behind a bush that did little to conceal him. He and other military men there saw us as a second potential invading force and they were taking no chances.

The gunman dressed all in white was a member of the “Ton-Ton-Maccoute” or “Bogey Men”, a para-military gang of thugs that was Duvalier’s private army. Dad obviously needed to go to shore to speak to this man, and while he rowed the dinghy with his back to the gunman, Mom forcefully called on a higher power with her rosary beads in hand. This man held us at gun point until later that evening when a 50-foot military vessel came down from Port-Au-Prince loaded with soldiers; they searched our boat from stem to stern, ripping open packages of soup and jello because “there might be bullets in there.”

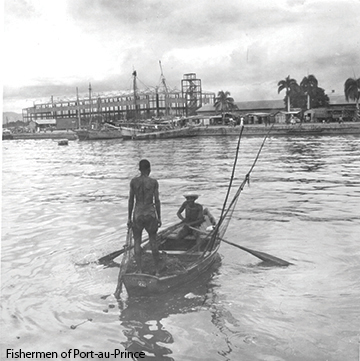

After they were finished searching us they began towing us under orders from Duvalier to Port-au-Prince some 45 miles away. We had no choice in the matter of course, and we were all quite frightened. When we arrived in Port-au-Prince, they then forced us at gunpoint to tie up at the main commercial shipping pier rather than the casino yacht club where a yacht would normally tie up. Not far from us was an open sewer outfall spewing raw sewage into the harbor. Dad immediately went to the American embassy in Port-au-Prince to ask for help but was turned down because in the words of the Ambassador, “He did not want to cause any diplomatic incidents.”

After a couple of days, an American aircraft carrier, the flagship of the then U.S. Navy’s Caribbean fleet, arrived in port. We received a visit from a Lieutenant J.G.off the ship who asked us if we could move our vessel as this was the dock where the aircraft carrier’s tenders would be off loading the sailors for their planned shore leave in Port-au-Prince.

My father responded to the request to move by asking the Lieutenant if he saw the man with the gun standing guard over our boat and that he was the reason why we could not move. This flagship was host to an Admiral who went to the government and compelled them to allow us to move our little sailboat to the casino marina docks.

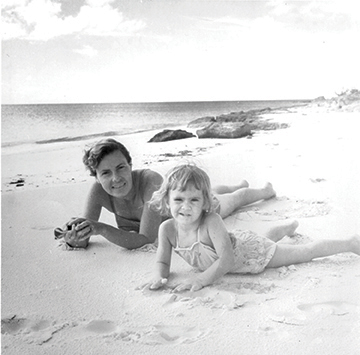

In the meantime, my baby sister Cynthia had became ill with dysentery from the filthy conditions at the harbor. We decided to go up into the mountains to the pleasant resort town of Pétion-Ville where we stayed at a hotel owned by Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Teddy Roosevelt’s rebellious daughter, while Cynthia recuperated. Enjoyably, we had lunch with Alice Roosevelt almost everyday while we were there and it was a beautiful, cool respite from Port-au-Prince.

Shortly after our stay in Pétion-Ville, we wound up back in Port-au-Prince, but now that we were being allowed to moor at the yacht club and Cynthia was better, we were more able to enjoy the tourist distractions that Port-au-Prince had to offer. Haiti in those days, while still one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere and in the grip of a brutal greedy dictator, was vastly different from the impoverished, completely benighted place we now know.

Port-au-Prince was a bustling city with an active tourist trade featuring luxury hotels with casinos and restaurants that offered gourmet French cuisine. With a prosperous but small middle and upper class, Haiti was in much better condition then, than she is now. After a little while, we decided it would be a good time to leave Haiti, so we set sail northward across the Gulf of Gonâve towards Môle Saint-Nicholas once again. We stopped there only to find out that Father Paul, our genial missionary host, had been put in jail. We were not told what the official reason was. We have often wondered what became of him?

Setting off from Môle Saint-Nicolas, we wondered if our problems in Haiti were over and we soon had an answer as we encountered one last difficulty on an over-night passage heading east along the north coast of Hispaniola. We were confronted by what appeared to be two lighthouses with the same light characteristic, which was very confusing.

Not wanting to take any chances, we anchored offshore for the night to await daylight. Dad assigned anchor watch to Nils in the cockpit, but he fell asleep only to be awakened by the powerful search light of, what seemed to him, a huge vessel looming over us. It was almost alongside of us and had stopped to render aid if it was needed. The north coast of Hispaniola is quite forbidding with tall mountains seemingly coming right down to the sea. The deep rocky coastal waters offer little shelter.

We had been told that there was an American owned sugar plantation at Cap-Haïtien, and when we arrived there we were once again welcomed with open arms by the generous American people who owned the plantation. The family had come down to greet us at the dock and, when they spotted Cynthia and me aboard our boat, they said, “We are having a Halloween party for the kids Please join us.”

The party was complete with American-style trick or treating and very enjoyable. We stayed in Cap-Haïtien for a week or so, while Mom and Dad tried to take care of some family business. Cap-Haïtien was also a tourist destination in Haiti with beautiful colonial architecture and interesting history dating back to before the American revolution.

Heading east, once again, along the coast of the Dominican Republic, we found ourselves in a delightful place called Sosúa, not far from Puerto Plata. While anchored off the beach in this peaceful bay, a chance encounter between myself and a group of boys playing on the beach led to my family’s introduction to Walter Biller, a leader of the colony of Jewish refugees from World War II, who had settled there and started a very prosperous diary and farming collective. Once again, another group of warm friendly people opened their hearts and homes to us with incomparable hospitality. The teens even tried to show Nils how to do a folk dance to Hava Nagila.

Our original goal had been to head as far south into the Caribbean as time and funds would allow but now both of these commodities were in short supply, as well as Mom’s tolerance for the rigors of the cruise and her concern for the proper raising of her family.

This cruise had been far more educational in many more areas of what children need to learn to become adults, as cruising sailors around the world know and understand. But Mom worried that we needed the basics that a formal education would give.

Mom and Dad had not ignored our education. They had obtained on my behalf, teaching materials for the third grade from the well-known Calvert School. But with the cruising life, being the busy experience that it is, we probably got only three lessons done.

People who have never cruised always ask us “So what do you do all day? You must get bored stiff?” And we cruising sailors laugh knowing how richly busy the cruising life can be. Dad was so busy that he got very little writing done and was not able to sell any stories. But evidently our education did not suffer because I wound up skipping the third grade and Nils who had left Tabor Academy in midterm skipped a grade of high school as well.

We spent quite a lot of time with the warm friendly people of the Sosúa Colony, invited to dinner at a different house every night. Cruising people seem to bring to life the “wonder-lust dreams” of shore bound people who like to live vicariously through cruisers experience.

Sosúa was to have been our jumping off point for sailing deeper into the Caribbean. But when crossing the Mona passage between Hispaniola and the island of Puerto Rico proved to be as much of a challenge as it usually is, an important decision was made and we turned north toward Great Inagua Island and the southeastern Bahamas, and then planned to head back to Florida. Lord knows, we had been through quite a lot in four and half months and even a fantastic good sport like my mother had reached her limit.

Great Inagua is owned by the Morton Salt Company where they produce salt in a solar evaporation process of sea water. The Morton Company on 300,000 acres produces a million pounds of salt a year; it was the second largest salt operation in North America. Huge evaporation pans or flats cover the island and the salt making process includes flamingos and brine shrimp in an interesting cycle of man and nature working together.

The place was managed by an English couple named Forrestal who showed us more hospitality, and they fed us countless bran muffins (back then people like that where known as “Health Nuts”); they even threw a party for my ninth birthday. Years later when I was a delivery captain taking a sailboat to Saint Thomas, I was having electrical problems. I put into Great Inagua knowing that the salt company had a machine shop. I was helped by the manager who had worked for the Forrestal’s, our hosts from before. When I called him on the phone as I was leaving to thank him for the assistance and expressing that I didn’t know if I would ever be back again, his reply was, “Oh, I don’t know, you have been coming through here since you were nine years old, you’ll probably be back”

Continuing northwest from Great Inagua we had some long deep bluewater stretches as we make our way through Mira Por Vos and Crooked Island Passages. It was along this part of the cruise that we experienced some of our most successful fishing under sail. At one point, we caught a beautiful dolphin (mahi mahi), which led to Cynthia uttering a phrase which she still has yet to live down. As Dad was cutting up and filleting the fish, cute little Cynthia, prone to being Miss Malaprop, said “ Oh, oh Daddy, fish bwoke”.

We then sailed along the west coast of Long Island creating great memories of peaceful deserted anchorages and wonderful beach picnics and Nils and I sleeping ashore on the beach. Sailing up Exuma Sound provided some of the most pleasant and relaxing sailing of the cruise. It should be mentioned that in the Bahamas as everywhere else we cruised, we saw very few other yachts and until we reached Nassau we had seen no other American yachts on the entire cruise. Our cruising family was a rare thing in 1958.

The Exumas, where delightful Staniel Cay stands out particularly as one of the best stops on our way to Nassau, even then the fishing and diving were excellent. Nassau Yacht Haven was our next big stop and we were starting to get excited about the fact that we were going to live in Florida.

When we originally came to Florida to buy Winds Way from yacht broker Richard Bertram, who was selling it for the University of Miami and begin the voyage, my family had spent the previous 10 years living in Mexico, where Cynthia and I were born.

It was very exciting to contemplate living in the U.S. and we were looking forward to it. We sailed into Bahia Mar in Ft. Lauderdale on Dec. 23, 1958 and as we prepared for Christmas, we told Cynthia that Santa was going to land his sleigh on deck and come down through the skylight to deliver the presents. We even had a little top of a real Christmas tree which we decorated on Christmas Eve.

We spent several months living aboard at Bahia Mar, where I had my first sales job making money selling nickel newspapers to the sightseeing boats and yachts at Bahia Mar until we moved into the house we purchased in Ft. Lauderdale.

Spending large amounts of time cruising on a boat is, I think, one of the greatest and most rewarding things parents can do for their children and our parents did it in style! My siblings and I are forever grateful to them for all of the amazing experiences as we sailed to the revolutions.