A seasoned offshore sailor and business consultant takes a systematic approach to managing risk for those heading off passagemaking (published February 2017)

November is not the best month for sailing from the U.S. East Coast to the Caribbean, but for lots of reasons, that’s when most of us sail down. Between the frequent gales coming out of the northeast, opposing Gulf Stream current and squally weather north of the islands, there are often plenty of opportunities for boat damage, gear failure, crew injury and the like. It was this subject, things that go wrong at sea, that was the topic of discussion for a number of us at a local BVI watering hole not too many days after a recent passage south.

One captain recounted how a squall had come up out of nowhere and the microburst blew out his jib. Another described how a crew member had slipped on the companionway steps and broken his wrist. And still another, me, recounted how a crash jibe had led to a bent vang. The ensuing conversation suggested that these were the typical, and almost expected, mishaps associated with a challenging ocean passage. Weather gods act out, people make mistakes, hardware fails, and despite extensive safety precautions, some amount of “stuff” happens. While one of the old salts at the table suggested it was the sailor’s fate, I wasn’t so sure I wanted to accept that.

Regardless of the level of preparation, we all take on some level of risk when we head offshore. And let’s face it, we can’t expect to complete every voyage with zero equipment failures or injuries. Or can we? Are at least some accidents inevitable in risky endeavors such as ours, or are we setting our standards too low? Is it possible that a paradigm shift in our thinking, to one of zero tolerance for accidents, coupled with a proactive approach to reducing the risk of those accidents, could significantly change outcomes?

Over the last 10-to-15 years, commercial industry has embraced Risk Management as a more aggressive approach to reducing workplace accidents. My personal experience in the manufacturing industry taught me that a change in attitude from the pragmatic, “some level of accidents are inevitable so we should work hard to reduce them”, to the proactive, “all accidents can be avoided if we remove the underlying risk factors”, made for a significant reduction in accidents.

Offshore sailing is no different than manufacturing in this sense. They both can be inherently dangerous environments. But that does not mean that accidents are inevitable. In both environments, a proactive approach to identifying and mitigating risks, that is, removing the potential for accidents, can significantly reduce sailing injuries and equipment failures. For offshore sailing captains, making the paradigm shift from, “…some accidents are inevitable” to, “…zero tolerance for injuries or equipment failures” is overdue.

Many initiatives aimed at improving safety at sea are ongoing and surely have helped reduce injuries and deaths. But these efforts tend to be generic approaches to physical safety based on lessons learned and do not provide a systematic approach to evaluating and mitigating the risks being faced by a particular crew on a particular vessel preparing to embark on a specific passage. The Risk Management process provides a proactive approach that each captain and crew can apply to significantly reduce injury or accident at sea. So what is Risk Management?

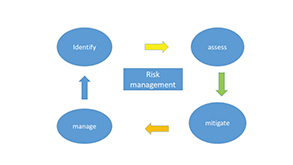

Paraphrasing a bit, Risk Management is the identification, assessment, and prioritization of risks followed by the application of resources to mitigate the probability of occurrence and severity of impact of unfortunate events or maximize the likelihood of achieving an objective.

Risk Management transforms the intangible appreciation that in any complex and hazardous endeavor some things will likely go wrong into a set of specific, tangible and actionable steps that can reduce both the likelihood and severity of those events actually happening. Risk Management encompasses the spectrum of equipment, technology, human factors and the environment to generate an inclusive and comprehensive plan to accomplish a goal, for example, to complete an offshore passage to the Caribbean, with the minimum disruption due to unforeseen negative events. A simplified flow diagram is shown on page 40.

We will delve deeper into each of these areas but the process begins with Identifying any risks to the safe and efficient completion of the voyage, to include injuries, equipment failures, environmental factors, etc. Consider Risk Multipliers. Next, we Assess the vulnerability of crew and ship to these risks and score the Probability of Occurrence and Severity of Impact should the risk be realized. This step includes preparing a Risk Matrix and determining initial overall risk.

The Mitigate step reduces both the Probability of Occurrence and the Severity of Impact with specific actions and then prioritizes and implements those actions based on resources and time available. We then update the Risk Matrix and determine the resultant overall risk. The final step is to Manage any resultant remaining risks.

IDENTIFY RISKS

Begin by preparing a simple Mission Description. A short statement of your objectives for the voyage that everyone can agree with. For example: “…to safely and efficiently sail (boat name) from (origin) to (destination) while incurring zero injuries and no equipment damage. We will depart as closely as possible to (date) and expect to spend (X) days en route. Our emphasis will be on crew comfort and safety over speed so we will accept delays on both departure and arrival dates.”

Begin by preparing a simple Mission Description. A short statement of your objectives for the voyage that everyone can agree with. For example: “…to safely and efficiently sail (boat name) from (origin) to (destination) while incurring zero injuries and no equipment damage. We will depart as closely as possible to (date) and expect to spend (X) days en route. Our emphasis will be on crew comfort and safety over speed so we will accept delays on both departure and arrival dates.”

Alternatively, the last sentence might read, “…weather permitting, we intend to sail fast and exploit the performance characteristics of our boat in order to minimize our time at sea.” Without suggesting which approach might be safer, each will create different demands on crew and equipment, potentially leading to different risks being identified.

The next step is to develop the list of risks. This can be done in a variety of ways and can include a sit-down brainstorming session, above and below deck walk arounds, and practice sails. The objective is to exercise as many boat systems and sailing activities as possible while constantly looking for anything that might go wrong. A few examples of identified risks might look like this:

- There is a risk that a crew member might trip on the reefing line as the line crosses the deck

- There is a risk that the GENSET might fail and we will be unable to re-charge the batteries

Next we brainstorm any possible risk multipliers. These are factors that are capable of increasing either the probability or the severity across the board. In our notional case, we chose four risk multipliers:

- Crew experience—we have two crew with limited offshore experience

- Crew age and health—we have two crew in their late 60’s

- Sleep deprivation—tired crew make mistakes

- Weather—the North Atlantic in November can be unpredictable

At the completion of the Identify process we have built a list of maybe 15-20 risks and the list looks like this:

ASSESS

ASSESS

During the assessment phase, each risk is discussed and assigned both a Probability of Occurrence (Po) and a Severity of Impact (Si) score. While this is a distinct phase in the process, it is practical to combine the Identify and Assess processes so the Po and Si are discussed among the crew as they are identified. This can speed up the process as it will eliminate low level risks before they get on the list.

In our case, the crew decided to drop the GENSET failure from the risk list as the main engine is capable of charging the batteries and there is a stand-alone battery bank capable of maintaining the navigation lights, radios and basic GPS capability. At the completion of the Identify and Assess steps, it may be helpful to lay out the risks on a grid and see where the combine risk index falls for the trip:

MITIGATE

This is the action oriented step. Here is where we come up with specific actions that will either reduce the Probability or Severity or preferably both. We look at the context of the risk and then develop mitigation actions. For example if the general risk is “Falls” and the specific context is the companionway ladder, then we come up with physical changes, procedures or Standing Orders to reduce or eliminate the risk. In the case of the Falling risk at the companionway ladder, a new Standing Order to always use the companionway as a ladder (facing the steps) rather than stairs, reduced the falling risk from Medium to Low.

This is the action oriented step. Here is where we come up with specific actions that will either reduce the Probability or Severity or preferably both. We look at the context of the risk and then develop mitigation actions. For example if the general risk is “Falls” and the specific context is the companionway ladder, then we come up with physical changes, procedures or Standing Orders to reduce or eliminate the risk. In the case of the Falling risk at the companionway ladder, a new Standing Order to always use the companionway as a ladder (facing the steps) rather than stairs, reduced the falling risk from Medium to Low.

So here are some examples of recent Identify, Assess and Mitigate steps prior to recent voyages south. For continuity, I have combined the Identify, Assess and Mitigate steps for each risk.

MOB

We decided to evaluate the MOB risk first since it is often a hot topic among offshore sailors. Our initial score identified the risk as a Low Probability but Very High Severity. We discussed opportunities to reduce the Probability of Occurrence, that is, the probability that someone would fall overboard, and our list of mitigation actions looked like this:

- Jack lines—already in place on deck and in the cockpit

- PFD/harness and tethers—all crew were so equipped

- Standing orders—available but could use update on when jack lines use is required

It was agreed that the best approach to reducing the probability of a MOB incident was to strengthen the standing orders to require 24/7 wearing of the PFD/harness while on deck and use of tethers whenever outside the cockpit, at night or in inclement weather. We all agreed that mandatory use of a tether in the cockpit during calm, daylight conditions did not appreciably reduce the Probability of Occurrence so we stopped short of requiring 24/7 use of tethers. We did stipulate that at any time there was only one person topside, that person must be tethered and must remain in the cockpit. With these adjustments to the Standing Orders we agreed that the Probability had moved from Low to Very Low.

Next we looked at the Severity of impact. That is, assuming there is a MOB event, how severe is the outcome. Our mitigation steps included first making sure the MOB stayed attached to the boat, and second, if not attached, then able to be found and recovered. Our list of actions looked like this:

- PFD/Harness with crotch strap—not all crew had crotch straps and this was considered to be the greatest risk to a MOB becoming separated from the boat, assuming the Standing orders regarding use of tethers were followed

- MOM-8—installed. Deployment training required

- Life Sling—installed. Deployment training required

- Personal Locator Beacons—we have AIS type beacons for each watch member and some crew had their own Personal EPIRB’s

- MOB recovery method—our Standing Orders described the Quick Stop maneuver and an MOB hoisting approach

- Training—we had not practiced the quick stop maneuver with this crew on this boat, nor had we demonstrated how to recover a MOB from the water using a spinnaker halyard and winch. We also did not have a plan to deal with a comatose MOB.

We agreed that those without them would add crotch straps and we would rehearse MOB recovery on the water, to include plans for recovering a comatose victim, before we departed. While any MOB event is serious, we determined that with these steps we could reduce the Severity from Very High to High since we now had greater confidence that an MOB could be recovered successfully.

TRIPPING & FALLING

At an overall High Probability of Occurrence and High Severity of Impact, trips and falls are an all-too-common event on an ocean voyage and are often a step in the sequence of a MOB. Rough seas, common to the November run from New England to the Caribbean, are often a contributing factor to the Probability of Occurrence.

Our approach to first Identify and then Mitigate was a detailed walk-around of the boat looking for potential hazards. After the walk around, our list looked like this:

- Companionway ladder—on Chasseur the ladder is gradual enough to suggest one can take the four steps down to the saloon facing forward. But this puts one’s feet on the slippery forward edge of the varnished step and not on the non-skid tread. We all agreed that the steps would be treated as a ladder, with crew facing aft when using them. Admittedly, this rule required constant reinforcement by the captain!

- Inner Staysail furling line—crosses forward deck at ankle level; too difficult to re-route so added reflective tape to the line

- Boom preventer attachment—the preventer attaches to the end of the boom, which requires some extended reach beyond the safe confines of the cockpit and a bit of a balancing act to connect. We added a loop of line to reduce the reach and allow the furling line to be attached from the cockpit.

- Throttle/Gear shifter—Chasseur has a step-through cockpit combing that is often cluttered with sheets and furling lines during sail adjustments and a trip here often results in a reach to the binnacle and a grab for the nearest object, the throttle or gear shift. Bad news if the engine is running. We agreed that a hand would go to the grab bar on the top of the binnacle whenever traversing the step-through, whether needed or not. Thus conditioned, an off-balance crew would be most likely to grab the hand hold rather than the throttle.

Re-scoring the Trip/Fall risk dropped all of the Po ratings and some of the Si evaluations, allowing us to revise the overall score from High/High to Low Medium.

EQUIPMENT FAILURE

Our definition of a successful voyage includes not only a goal of zero injuries but also zero equipment failures and an on-time arrival. We approached equipment failure risk in a fashion similar to the others, with a walk around and then by taking notes during a familiarization sail prior to departure. Our list came out like this:

- Main sail luff tape—easy to tear the tape during mainsail furling operations. We agreed only the captain would furl the main until watch captains were fully trained

- Crash gibes—Preventer installed, but will not completely protect against an inadvertent gibe. Risk is greatest while running at night due to wind shifts and disorientation. Our mitigation included a number of procedures:

Crew members would hand steer at least 50 percent, both night and day to insure adequate helm experience

Downwind sailing angles limited to 145 degrees apparent at night to provide adequate control margin

Radar to be used at night to track and avoid squalls

- Chafe to sails and running rigging —Mitigate with daily inspection. Each watch to ensure furling lines are taught at all times.

- Standing rigging failure—Chasseur has rod rigging with recent rig inspection. Daily visual and hands-on check of rig tension are specified in Standing Orders.

- Sail damage—risk was considered greatest at night with full sail in squally conditions. We decided that we would carry full sail at night unless the evening weather report forecast changed or radar identified squalls or convection in the area. Under these conditions, a preemptory reef would be tucked into the main.

- GENSET or engine failure—we carry significant spares and a large battery bank. A separate bank backs up nav lights and radios. The risk of an engine failure we can’t fix is low and the severity also low.

CREW HEALTH

We shared each other’s health issues, prescription drug requirements, proclivity for sea sickness and the like. Most of the crew had extensive offshore experience and had proven techniques for dealing with sea sickness. For the two inexperienced crew we recommended Stugeron. We inventoried the ship’s first aid kit, antibiotics and pain meds and were comfortable we could treat most illnesses or injuries.

RISK MULTIPLIERS

Sleep deprivation can be a major contributory risk, imparting a negative impact to all other risk Probabilities, essentially a risk multiplier. With a crew of five, we scheduled two watch teams of two each, with me floating. I handled navigation, communication and boat systems and relieved individual crew members on a rotational basis to give each crew member a few hours extra sleep every few days. During periods of rough weather I would augment the on-watch team for sail adjustments. Otherwise, my job was to be fully rested should I be called upon to fill in for a disabled crew.

We treat weather as another risk multiplier. Everything becomes more challenging as the sea state increases. Reducing the risk of weather impacts brings the overall risk factor down. We do this by getting the best possible advice prior to leaving, and then ensuring we have multiple sources and methods for getting updates en route. Sailing efficiently and maintaining our speed keeps us on schedule and reduces our exposure.

Our primary method of accessing weather products offshore is our SSB, backed up by our Iridium sat phone. Besides the NOAA products we employ contract weather routing services from Commander’s Weather and Chris Parker. We also have a weather FAX machine but rarely use it these days.

All that data isn’t of much use unless applied effectively to sailing plans. In our case, we schedule a morning and evening watch overlap where we share a meal and discuss the forecast and our options. I have found that the team often arrives at better decisions than I alone, especially if I am a bit tired. On a prior trip south, faced with betting on a predicted wind shift or sailing the best VMG at the time, the team voted to go for the wind shift, overruling my vote for the VMG now, and we were rewarded nicely. Effective crew coordination can be another powerful risk mitigator.

MONITOR

Every boat, crew and passage is unique, so your list of risks will surely look quite different than ours, as will your mitigation approach. All that matters is that the mitigation process results in a significant reduction in overall risk. Once you have done your best with your Mitigation process, then it is time to go sailing while evaluating the effectiveness of your plans and monitoring for new risks. On arrival, and before everyone disappears to the bars, it a good idea to plan a short lessons learned session to capture what worked and what did not.

SUMMARY

The Risk Management process can only work with buy-in from the entire crew, especially if the mitigation involves changes to their normal sailing behavior. Some individuals might balk at one mitigation action or another, such as how they are to take the companionway ladder, or when they must wear their PFD, but once they have bought into the process as a team, and see the positive effect on the Risk score, they are more likely to comply. And if they don’t then it may be time to look for more supportive crew.

It takes more than a safety-minded attitude to reduce risk of injury when engaged in inherently hazardous endeavors such as offshore sailing. A more proactive approach such as a Risk Management program can provide that added margin of safety to an otherwise safe boat.

Greg Smith is an experienced offshore sailor, with multiple trips to the Bahamas, Caribbean and Bermuda. He holds USCG 100t Master Credentials and is a member of the New York Yacht Club. His home port is Newport, RI.