Exploring Bahia de Caraquez, Ecuador (published May 2012)

With the depth alarm screaming, we entered the surf line and I threw the wheel all the way to starboard, struggling to keep our 64-foot steel schooner from broaching. A 14-foot breaking wave had quickly enveloped us and our stern rose alarmingly, heeling us over 40 degrees as we began to surf: 10, 12, 14 knots. We peeled off nearly out of control, rushing down the face of that first big wave. Seconds later, the second roaring breaker rose above the cockpit and swept by, foaming angrily on either side of us over the boiling shoals while exploding on our mid-deck.

I fought for control as sounds of breaking glass and a guitar being thrown across the cabin were mixed with shouts of concern from our pilot and crew. A third wave lifted us almost as high, but I had applied enough power, and we surfed this and two more waves with better control before the pilot advised me that we had crossed the first bar and that we now needed to turn.

Swinging One World hard to port, we made our dash parallel to the shore with 10- to 12-foot breakers just off our port side and the rocky beach no more than a stone’s throw to leeward. “If the engine fails,” I thought to myself, “we are screwed.” But our reliable Ford diesel kept going, and after a few more waves rushed by, we were able to turn the final corner and enter the calm waters of the Rio Chone. With the crashing surf now safely on the other side of the spit of land that forms one of the most protected harbors along the western South American coast, we all breathed huge sighs of relief. Compared to our first time coming into the harbor two months earlier, this had been a nightmare!

THE WAITING ROOM

Originally intending to make a direct passage from the Perlas Islands of Panama to the Galapagos, we had been tempted by reports of Ecuador from a handful of cruisers who told stories of a beautiful coast seldom visited by cruising yachts. The prospect of spending a few weeks exploring this geologically striking and culturally diverse country intrigued us.

In the northern winter season, if one is lucky, it is possible to grab a fair wind out of the Gulf of Panama and carry it well over halfway to the Galapagos. But in many cases, the following breeze leaves within a day or two and there are still many hundreds of miles of motoring through flat calms to make the elusive Enchanted Isles, as the Galapagos are sometimes known. So when we lost all the wind on day two out of the Las Perlas, we decided to detour to Bahia de Caraquez, 550 miles south of Panama City and roughly at the halfway point on our route to the Galapagos Islands. Adding only 200 miles onto the overall distance to San Cristobal, Galapagos, we felt that the chance to explore the Andes and upper Amazon Basin from public transport routes while the boat was safely moored in a protected harbor, and to take on diesel at government subsidized prices of $1.50 per gallon, more than justified the delay.

Day three saw us motoring on a glassy rolling sea as we made our way down the Colombian coast, staying about 100 miles off and in a good following current. On the fourth day we began closing the Ecuador coastline and crossed the equator by midday, still about 30 miles offshore but well into Ecuadoran waters. With One World stopped, we all went for a celebratory swim and drifted back across the equator because we were now in the north setting current that can usually be found close to the South American coast. By late afternoon we had raised the Bahia de Caraquez skyline. What at first appeared to be a very large city with skyscrapers and a vast urban area turned out, as we got closer, to be a small city with a scattering of 10- to 12-story apartment buildings; a vacation town with a small business district set well back from a rocky, sea walled waterfront. By nightfall, we were at anchor in the open roadstead anchorage a mile off the town, having missed the high tide needed for entry to the harbor by an hour. Locally known as the “Waiting Room,” the anchorage was a bit rough and we kept an anchor watch until well after midnight, after which the land breeze came up and the seas settled down.

A CHARMING DETOUR

In order to get into the river and the protected harbor behind the town, it is necessary to enter on a high tide and it is strongly suggested that it be done with a local pilot aboard who knows where the sandbars, channels and reefs are. With only nine to 10 feet of water in the channel at high tide and a tidal range of approximately 10 feet, we were lucky to have the Puerto Amistad Marina send out a man named Ariosto, who had more than 20 years of experience on the river, to guide us through the circuitous channel. We waited until the following afternoon for the high tide that would allow us to make it in, and with Ariosto’s expert help, had an uneventful crossing of the bar.

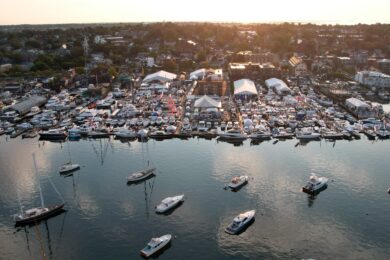

Having made arrangements in advance of our arrival with Puerto Amistad via our Sailmail SSB service, we were directed to a beefy mooring, where we were met by the health and port captain officials just minutes after securing. Within half an hour, formalities were underway and we were asked to go ashore. The marina owner and local clearance agent, Tripp Martin, took our ship’s papers and passports, promising to finish the check-in procedure for us. Tripp and his wife Maye made us feel welcome and the staff of Puerto Amistad was helpful and friendly. The marina, which was just a crumbling commercial dock when the couple bought the facility a few years back, has been transformed into the nicest restaurant in Bahia with its well-tended grounds, shower and restroom facilities, laundry and wireless Internet cabana. The marina was clean and safe at any time of the day or night.

The mooring field is in the main channel of the Rio Chone, a major river on this stretch of coastline, so after heavy rains debris, or even whole trees, could come down river on the ebbing tide. Puerto Amistad maintains a 24-hour harbor watch boat with two men who not only provide security, but keep the boats free of branches and flotsam. These men also provide bottled drinking water, diesel and gas, and offered to assist us with small chores on the boat. One fellow known as Ray was especially helpful in watching our boat while we went inland. Bahia is far enough south along the west coast to not be affected by the rainy season weather typically found a short distance up the coast in Colombia and on toward Central America. Because of the low cost for a mooring, the quaint, safe little city, and a fairly arid climate, many people store their boats here long term—an inexpensive and safe place to stop while exploring inland or heading back home for a while.

After meeting with Tripp, we were given permission to roam the town. And what a charming and friendly town Bahia turned out to be. The shopping was quite good and although the selection was not as varied as that in Panama, I would not hesitate to do a major provisioning. Prices were generally one-third less than in Panama, and the city market, open every morning at 7am, proved to be one of the best we have ever visited. Ecuadorans are big on fishing, and the average price for fresh fish, regardless of the type, was $3/pound. You never knew what to expect in the market—one morning we saw a 10-foot shark being filleted! Ecuador is well known for its shrimp exports, and we even found organically raised shrimp in the market at very good prices.

My 18-year-old son and his girlfriend are avid surfers and it didn’t take long for them to find out that just a 35 cent ferry ride and a 25 cent bus ride away was the surfer Mecca of Canoa, world-renowned for its miles of sand breaks and funky beach party lifestyle. While they took off on a five-day trip into the Amazon headwaters to visit a shaman they had heard about and traveled to some indigenous villages, we took buses into the Andes to Quito and Otavalo, then on to quiet, quaint Cotacachi, where I have relatives. After a week of land travel, we set about preparing for the next leg of our journey.

RETURN PASSAGE

We left Bahia in the company of a well-known French cruising couple on Asterie, and after three days of motoring and one good day of sailing, reached the Galapagos. We spent a blissful month cruising several of the main islands, and in early April, made the return trip to Bahia de Caraquez. By taking advantage of the new OSCAR real-time current data from NOAA’s web service, we found the most favorable way against the current to allow us back to the coast. Making the run in four-and-a-half days from Isabella Island, we once again missed the high tide by about an hour and had to spend the night outside in the “Waiting Room.”

Conditions on that entry were much less than ideal. In fact, after the harrowing run across the bar the next day, Ariosto told us that the pilot boat that would normally have brought him out had refused to go, so he had hired a different boat, which was slammed so heavily on one of the huge waves coming across the bar that it had cracked its hull. Ariosto also told us, after we were safely in the river, that in more than 20 years of bringing people in over the bar, this had been the scariest entry he had ever done, but that because he knew how strong our boat was, he had agreed to let us try. Not sure what to think about that!

Our second visit to Bahia was even better than our first. We had made friends ashore and knew our way around, and in no time we had re-provisioned and prepared for continuing on. With the work done, we relaxed and took long walks every evening, ate in some great little restaurants for an average price of $15 for two people (including drinks), went sightseeing in the surrounding area and felt rested and ready to carry on after 10 days.

Our fourth crossing of the Rio Chone bar was so easy that it was barely noticeable. Once again, more because of loyalty than anything else, we had Ariosto pilot us over the river bar. By now I had three GPS tracks to show us the way out, but after the bravery he had shown in bringing us in previously, we wanted to give him the work.

After we had cleared the bar and were safely out at sea, the girls gave him hugs and we shook hands. He jumped off onto the waiting pilot boat and waved as we set out for Panama and our return to the Caribbean. Seeing the skyline of Bahia slowly recede into the sea, we all knew that we had come across a very special place, and hoped that we would have the good fortune to cruise that way again.

After returning to Panama, Todd Duff and Gayle Suhich sold their schooner One World and are now cruising the Caribbean on their 42’ Westsail ketch, Small World.