How to plan a fall passage from the East Coast to the tropics (published September 2016)

Several falls ago, I found myself aboard Peter Johnstone’s 68-foot sled Mojo headed south from Newport, RI to Antigua in the eastern Caribbean. We had caught the tail end of a fresh cold front for our departure and rode it at high speed all the way to the Gulf Stream where the wind abated and we crossed without incident. We, and several other boats, were headed in the direction of Bermuda, which offers a good “Plan B” landfall should the weather turn nasty out there. And it did turn nasty.

As often happens in fall in the western North Atlantic, a little but deep low that formed south of Cape Hatteras began moving toward us on a collision course. This promised to give us 30 knots or more of headwinds as we struggled toward the safety of Bermuda. But we opted for a different solution. We turned right from our southeastward course to the south west and reached easily more or less in the direction of Hatteras for 12 hours.

By reaching southwest, we let the low pass to the south of us and we could use the shifting winds, from south east, to northwest to North and then northwest, to our advantage. At the end of 48 hours, the low was well to the east of us and we had sling-shotted around behind it and popped out into the fair weather 200 miles south of Bermuda. From there our course took us through the Horse Latitudes and into the easterly Trades Winds that we beamed reached across all the way to Antigua. Meanwhile, our friends on the other boats were determined to get to Bermuda and had gale force headwinds for 48 hours and then an expensive layover while the storm passed.

The trip was a good one and showed us all of the variables that have to be mastered when you plan and execute a passage south from the East Coast to the tropics.

The trip was a good one and showed us all of the variables that have to be mastered when you plan and execute a passage south from the East Coast to the tropics.

SETTING THE STAGE

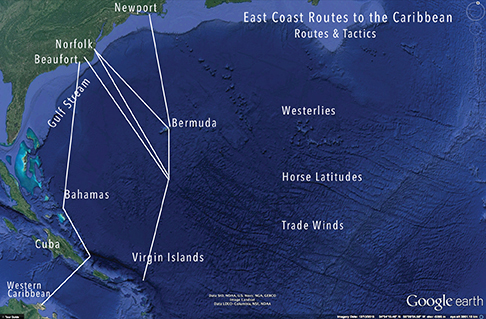

The western North Atlantic and the passage south to the tropics presents three large natural weather patterns that have to be negotiated wisely and safely. The dominant winds north of about 25 degrees north are the prevailing westerlies that blow around the world.

South of 25 degree north, you run into what are known as the Horse Latitudes where the wind is often variable and calms can prevail. This windless band got its name, purportedly, in the days of Spanish exploration when horses being transported to the new world often died of thirst and had to be tipped over the ships’ sides.

South of the Horse Latitudes you sail into the easterly trade winds that form along the south side of the Atlantic High and flow from the Canary Islands in the east all the way to Central America and out in to the Pacific. All of these systems are affected in some way by the giant force of the Gulf Stream that carries hot water from the Florida Straits all the way to Ireland.

Given these variables, the western North Atlantic is one of the more complex bodies of water to sail through, particularly in the fall when the jet stream often starts to move south across North America and the Atlantic High or Azores High begins its annual migration southward toward the tropics. Complicating this picture is the fact the Atlantic is cooling quite rapidly while the waters of the Gulf of Mexico remain warm and the air above it full of moisture.

Two types of bad weather are generated from these weather phenomena. The first is a cold front pattern that drives ridges of pressure off the American coast and over the ocean. These cold fronts often pack a lot of wind and can, over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream and south of it, create little weather bombs dominated by thunder storms and very windy squalls. You really don’t want to be anywhere between the Northeast and Bermuda when one of these systems is boiling.

The other type of storm is the one we found on our passage south aboard Mojo. These are tropical revolving systems that are created by the shear of moist air in a warm front colliding with the much colder air being driven by the jet steam. This usually happens in the waters between Cape Fear and Hatteras and the systems then track northeast into the Gulf Stream where they catch fire from all of the warm, moist air rising from the stream. At this point the storm has become an extra-tropical low and has the ability to cause mayhem to boats in its path.

Once into the Horse Latitudes and on into the tradewinds, the bad weather you encounter will mostly be very local squalls that can be mild or severe depending upon their size and intensity. Often you can see them forming on radar and navigate right around them. Sometimes you can’t and you have to reef down and batten the hatches. These tropical squalls are usually over in under an hour.

A PLAY IN THREE ACTS

With the stage laid out before you as you plan your passage south, it is good to think of the passage in three distinct segments.

With the stage laid out before you as you plan your passage south, it is good to think of the passage in three distinct segments.

The first act is getting across the Gulf Stream in one piece. The start of the passage is the only time when you will be able to pick your weather so you should do it carefully. What you are looking for is a weather window wide enough to get you through the stream before the next cold or warm front comes along. Since insurance companies insist that you wait until November to sail south, you are in a volatile season during which fronts come through just about every four days.

From ports north of Delaware Bay, you will need at least 48 hours to get to the stream and 60 hours to be through it and south into the warmer water and westerlies. The best weather windows here will be on the wind shift to the northwest after a cold front passes. With luck, you can ride the northwest breeze for two days before it shifts to the west and goes light on the third and fourth days.

One strategy for those sailing from the Northeast will be to head to Bermuda in October before the onset of the late fall gales and lay over there until November before heading south to the Caribbean. Weather windows are longer and the weather milder in October. And, with hurricane forecasting as comprehensive as it is, you will have ample warning of bad tropical systems. Check with your insurance company to see if they will allow you to do this.

The course from the North East is toward Bermuda. Once south of the stream, you take what comes and react in the best way possible.

From the Chesapeake Bay, you need about 24 hours to get clear of the stream so the weather window can be smaller and the opportunities to leave more frequent. The best option is to find the narrowest place in the stream to cross, which is often off Cape Hatteras.

South of Hatteras, Beaufort, NC, is the usual jumping off point for the Caribbean and is a good choice for boats leaving after the middle of November. Southeast of Beaufort, the stream is less forceful than is it farther north and more diffuse. With a clear 36 hours, you can be through the stream and on your way east.

The second act of the passage is to position the boat for a good angle of sailing in the tradewinds. The meridian at 65 degrees west is known among delivery skippers as “I 65” since sailing that far east before turning south will position the boat for a beam reach through the trades into the Virgin Islands. Opting to sail south west of I 65 will mean a hard beat into the trades for the last 300 miles or so.

Boats heading southeast from the Northeast that are not planning to stop in Bermuda may want to try to ride the westerlies north of Bermuda and then start to turn south at about 65 west. For those who stop in Bermuda, the best tactic is to wait for a fair westerly to carry you southeast until you can easily fetch the Virgins on a beam reach.

From the Chesapeake Bay, the route will be to cross the stream as noted and then head east southeast while aiming at a waypoint at around 65 west and 26 north. With luck, you will have westerlies for a few days to carry you into the Horse Latitudes and then may have to motor sail for 36 hours to find the trades. The rhumbline course from the Chesapeake to the BVI will take you into the trades far west of your destination—meaning a long uphill slog.

From Beaufort, the route is similar to that from the Chesapeake. Head east and southeast making for the waypoint at 65 west, 26 north and avoid the temptation to cut the corner early, even if the wind seems favorable. A short term gain in the middle will offer up pain in act three.

Act three is the last 300 miles to the islands of the Caribbean—most likely the Virgins or the BVI. If you have positioned yourself at 65 west or even farther east at 63 west, the run south through the trades should be a sleigh ride.

Once you get in the tropics, at this time of the year, you will be warm at last but also faced with the steady stream of pop up squalls that form along the boundary between the Horse Latitudes and the trades. You will have to dodge these all the way to the Virgins. You will see them on radar and can also judge their strength by the height and size of the huge billowing clouds above them. Rapid and strong convection aloft means stronger winds at the surface. If you can see under the squall, it will pass quickly. If you can’t, get ready for a blow.

There’s an old adage from the days of square riggers that is useful when dealing with tropical squalls:

When rain comes before the wind, dories, gear and vessel mind;

When wind comes before the rain, soon you’ll make the set again.

LANDFALL

LANDFALL

If you have had some cooperation from the weather, if you haven’t had a gear or sail problem, if the crew has all been healthy and agreeable and if you have played out a sound strategy to work your way through the three acts of the passage, then your reward is landfall on a tall topical isle where the palms trees rattle in the trades and the azure sea breaks on coral reefs and white sand beaches.

Since this is rum country, it is traditional to raise a tot of rum to salute the crew and to dash one tot over the side in tribute to Poseidon. Ahead for most will be a winter spent exploring the Caribbean and beyond. It’s an adventure well worth having and the passage south is the gauntlet you run to get there.