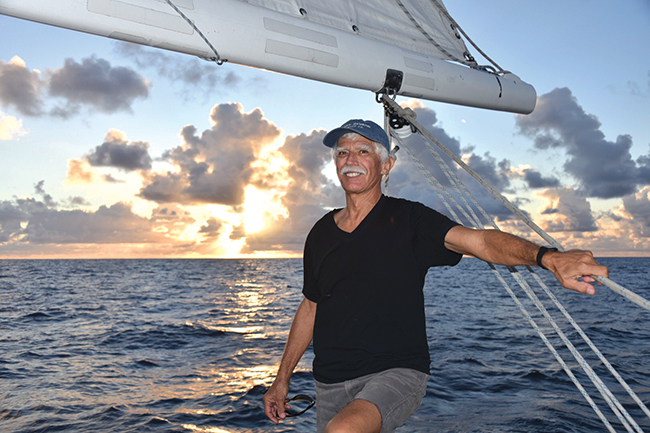

Having made the passage from Newport to the Caribbean dozens of times, the author skippers a big Swan in the NARC one last time and reflects on the challenges and pleasures of the offshore passage (published April 2018)

Strong gusts threw short rollers into the marina pinning our Nautor Swan 53 to the dock and drenching everything with spraying blasts of cold, October, Narragansett Bay water. The floating docks of the Yachting Center, in Newport, Rhode Island, morphed into a galloping coordination test to dance across. That weekend marked the five-year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, which ground to pieces the coasts of New Jersey and New York. Fortunately, this weather was no Sandy even though my charter guests came for a strong, open ocean adventure. If we had already been at sea, the 35 knots of wind would have been manageable but now, we were trapped in the marina until the spiraling storm system could spin away.

For many years, each fall, I had captained a large Swan sailboat for Offshore Passage Opportunities between Rhode Island and St.Maarten, with a stop in my favorite harbor in the world, St. George’s, Bermuda. For the past 10 years, my wife and I had sailed off to cruise the world on our Valiant 40, Brick House. With a decade of passagemaking behind us, we left our floating home in Malaysia for a brief return to New England. I could not pass up the invitation to skipper, one more last time, the most challenging, variable, fun passage in the world. Aurora, my new home for the next two weeks, was full of diesel, fresh water, and food for a crew of six. We were ready to cross an ocean except for the weather delay and one vital piece of equipment, a large sponge.

For many years, each fall, I had captained a large Swan sailboat for Offshore Passage Opportunities between Rhode Island and St.Maarten, with a stop in my favorite harbor in the world, St. George’s, Bermuda. For the past 10 years, my wife and I had sailed off to cruise the world on our Valiant 40, Brick House. With a decade of passagemaking behind us, we left our floating home in Malaysia for a brief return to New England. I could not pass up the invitation to skipper, one more last time, the most challenging, variable, fun passage in the world. Aurora, my new home for the next two weeks, was full of diesel, fresh water, and food for a crew of six. We were ready to cross an ocean except for the weather delay and one vital piece of equipment, a large sponge.

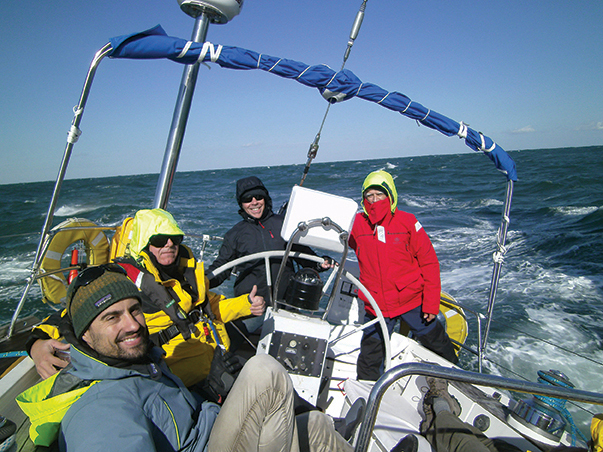

The charter crews on these trips have always proved to be a successful, intelligent and motivated group who know how to get along with others. We are one of three Swan charter boats, with paying charter guests, captained by professionals who long ago stopped counting their number of sea miles. There were also several privately owned, owner-operated boats that completed the group in which we would all sail together as the North Atlantic Rally to the Caribbean (the NARC).

The extra days in port gave the crew time to explore not only historic Newport but the recesses and intricacies of a boat full of systems and electronics plus the opportunity to size up their crewmates. In anticipation of worst weather ahead, we took off the owner’s 130-percent racing sail and bent on a more durable and properly sized 90-percent jib. Also on deck, the Dorade vents needed attention. When waves roll over a boat, simply turning a Dorade to face away from the wind and waves is not enough to keep water from washing below. Besides, the crisp chill of fall made it uncomfortably cold inside Aurora. To keep wind, cold, and water out, all the Dorades were covered with plastic bags and secured in place with light line.

Crew member Dave, stowed his gear in the aft cabin opposite my bunk. His short body builder frame complimented his energy and competence. If a conversation amongst the crew ever lagged, Dave always inserted an interesting spark. As a long-time commercial airline pilot, Dave slipped easily into the functions of a yacht far larger than his Catalina 27. Dave brought his plastic sextant and sight reduction tables to practice with. Maybe together we could learn what I had long ago forgotten.

Crew member Dave, stowed his gear in the aft cabin opposite my bunk. His short body builder frame complimented his energy and competence. If a conversation amongst the crew ever lagged, Dave always inserted an interesting spark. As a long-time commercial airline pilot, Dave slipped easily into the functions of a yacht far larger than his Catalina 27. Dave brought his plastic sextant and sight reduction tables to practice with. Maybe together we could learn what I had long ago forgotten.

The other four crew had their choice of the two stacked bunks forward on the port or the two bunks on the starboard bow. At this point in the trip, it is difficult to determine which would be the most leeward side, thus the most comfortable, for the majority of the passage.

We finally found the big cellulose sponge we needed at a hardware store. By Tuesday morning, 6 November, the wind settled to 15 knots so we backed Aurora out of the marina. We were on our way.

Layers of shirts and gloves broke the chill blowing across Narragansett Bay. I loved my new Henri Lloyd foul weather gear. The jacket stopped the wind and the unique Optivision hi-vis hood system allowed full peripheral vision. John ground fast and hard on the jib sheet winch working up a sweat as we practiced tacking. Materials transport is how the crew labeled John’s occupation, but with a chuckle, he more squarely says, “No, I am a truck driver”. He has read the classics like Slocum, which stoked the desire for a sea adventure his 26-foot sailboat won’t allow. He thought maybe in the mornings, he could stroll the decks and pick up flying fish to fry for breakfast.

Marko steered seaward as the rest of us worked the deck. His experience sailing his own 37-foot Island Packet made him quickly capable of maneuvering a highly responsive performance cruiser. At 30 years old, he is the youngest crew yet the most adventurous. Marko made a big news splash when he and two pals did a base jump off the top of the new World Trade Center, which left the police, FBI, and Homeland Security, unamused. He is working as a movie set carpenter to pay off lingering lawyer bills. Marko is gaining ocean experience before sailing his own boat to the Caribbean.

I am impressed with Keith. When I grab hold of the main halyard and hang with my full weight to hoist the large mainsail, it still won’t reach its final height. Keith can stand there and send the main up as though he is pulling on a string. Keith is the Hollywood image of the square bodied, bear strong, gravel voiced, Marine sergeant, which he was before he retired. He now specializes in telecommunications. Keith is trying ocean sailing to determine if he should become a fulltime sea gypsy.

The man I would eventually defer to for sail trim advice is Chris. Since childhood, he has been racing sailboats along the coast and on the Great Lakes. Chris analyzes billion-dollar companies to determine if they are worthy acquisitions for far larger companies. Chris is looking for an ocean crossing adventure.

On all my NARC trips, everyone has come from vastly different neighborhoods across America, yet by journey’s end they become a cohesive group of friends. This is one of the amazing things about sailing across an ocean.

The 200-foot-deep waters of Rhode Island Sound extend over 100 miles offshore before the ocean bottom drops away to depths of miles. It is a boisterous business crossing the shelf in 20 knots of wind after a strong spiraling storm sets up wave trains colliding from all directions. But the very bumpy ride was a nauseous experience for two of the crew who were soon spewing over the side. They did not follow good advise. It is always strongly advised to take seasick medicine at least six hours before leaving port. Those who followed the advice and wore a scopolamine patch, swallowed Bonine, or Dramamine-non drowsy, fared well. In Bermuda, the very effective product called Stugeron can be bought over the counter, but it is not sold in the U.S.. Crossing an ocean for the first time is not the place to be experimenting with ginger root or wrist bands when your shipmates are relying on you.

We did not talk, we yelled to each other over the ocean and wind noise as the breeze increased to 25 knots. Maximum sail was set, on a beam reach, which kept us moving at 10 knots over the ground and at times peaking at 12. The windward running back stay was set. The Swan loved this weather. Everyone had their turn on the large steering wheel in daylight before a watch schedule was set. Holding a compass course in bouncy weather is a learned skill everyone would become fully adept at on this trip. Steering with the wind on the beam meant the sails had to be trimmed properly so the boat would be balanced and not round up into the wind uncontrollably.

The weather router who gave the fleet briefing before departure predicted calms ahead. My wife Rebecca gave our crew similar weather information using her PredictWind program, a new weather prediction application. I had also loaded PredictWind onto my tablet specifically to test on this passage. But with PredictWind, as we headed into the north Atlantic, I could watch the daily wind arrows display for a far better interpretation than a one sheet handout. The PredictWind projection went out nine days. If we had on board Iridium Go! a satellite link, we could get daily weather updates. The same can be downloaded over the single sideband radio with a Pactor 3 modem.

The weather router who gave the fleet briefing before departure predicted calms ahead. My wife Rebecca gave our crew similar weather information using her PredictWind program, a new weather prediction application. I had also loaded PredictWind onto my tablet specifically to test on this passage. But with PredictWind, as we headed into the north Atlantic, I could watch the daily wind arrows display for a far better interpretation than a one sheet handout. The PredictWind projection went out nine days. If we had on board Iridium Go! a satellite link, we could get daily weather updates. The same can be downloaded over the single sideband radio with a Pactor 3 modem.

Natuor Swans are incredibly strong and seaworthy boats. I have all the confidence in the world in Swans, of any length. But John’s romance with the sea was being tested. In the famous sea stories he read from his easy chair he says “Those guys don’t tell how violently you get knocked around a cabin and how you have to crawl around the deck on all fours.” John was already hinting at jumping ship and flying away in Bermuda.

Rough weather is a perception based on one’s experience. Chris and Dave were looking for far higher wind speeds and waves to have an ocean experience that would increase their offshore skills. According to Dave, “Anyone can sail to Bermuda in this.”

As darkness approached, the watch rotation was set. Watch “A” was comprised of the three most adept crew. The watch consisted of three-hour shifts beginning on a whole hour. One and a half hours later, that is halfway through a shift, a crew from the “B” watch would come on deck on a half hour clock reading. So, halfway through a crew’s three hour watch, a new, fresh face would show up. With this system each man has three hours on and six off. Additionally, the system has a natural rotation so no one is stuck on the grave yard shift and everyone gets to see a sunrise and sunset. South of Bermuda, where life at sea is easier in the more settled weather and the crew has gained experience; a different watch system would be used.

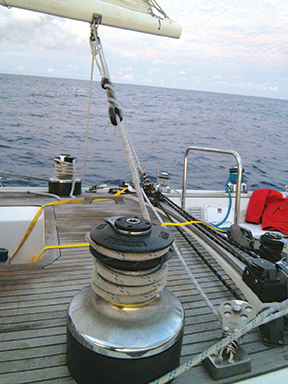

As predicted by the weather router and PredictWind, only 24 hours out of Newport, our wild ride over short waves and favorable beam wind ran out of steam.The wind died yet the residual waves roguishly combined into a sloppy froth of colliding waves. To keep the main sailfrom continuously slating at the end of its sheet, which can be terribly destructive to the sails, slides, gooseneck, and rigging, we set up a large rubber shock absorber. It started with a bowline to a bail on the boom near the mainsheet. The bitter end was then secured to a winch on the windward side of the boat. A preventer on the leeward rail completed the triangulation necessary to restrict the main. The main sheet was slackened so the initial shock was eased by the rubber absorber. If needed, a shock absorber can also be rigged to the jib sheet.

This 635 nautical mile passage, from Newport to Bermuda, was proving to be one of the most challenging ever. Never before has the wind died to leave a flat sea north of the Gulf Stream or been so consistently light and contrary, blowing right up our nose.

In Newport, the water temperature was 70 degrees. We watched the ocean temperature rise as we neared the Gulf Stream. With the warming water, the air too meant the crew would strip away layers of clothes to become more comfortable.

On the first calm, after the waves died away, we dropped the sails, and turned off the engine so we could take advantage of the flat, warmer water for the crew to plunge into an ocean where the bottom is over three miles deep. In that refreshing clear water we discovered how terribly fouled the propeller and prop shaft were. This fouling would at least double our fuel consumption and leave us dangerously low on fuel for our approach to the reef strewn coast of Bermuda, in very uncertain winds.

As we motorsailed south, it was a most unusual day as we approached the Stream. There was not the normal long bank of puffy cumulous clouds floating in a perfect line to mark the presence of the Stream. We knew we were in the Stream as the water temperature rose to 81 degrees. The wind had picked up to 15 knots yet came blowing out of the southeast, directly where we wanted to go. Blowing somewhat against the east flowing current, there was not the terrible standing waves one often hears about. In fact, for us, the wind against current helped us maintain the best course we could steer to Bermuda.

Near the northern edge of the Stream is where the yell of “fish on!” was heard. Keith and John fished with a “Cuban Yo-Yo” hand line with 100 yards of 300-pound test line. Keith let out only 50 feet of line to troll a colorful plastic Hoola Skirt lure with a single hook. Keith had a wild, strong, fish to work inch by inch, closer to a sailboat moving south as the fish struggled north. The hook was well set when the fat 10-pound tuna was lifted aboard. Flopping and vibrating wildly, the side deck and cockpit soon mirrored a bad Hollywood horror film. Thick red blood flew everywhere including the murderer’s face and foul weather jacket, until someone brought up the bottle of rubbing alcohol. Doused down its gills, the fish stopped thrashing, immediately.

We don’t want to catch fish bigger than that tuna. The small ones are difficult enough to deal with. That most valuable tool, the yellow cellulose sponge, began scrubbing its first chore working buckets of seawater into the grain of the teak deck to displace the slippery red mess and to change Keith’s foul weather gear from red back to yellow. More situations would put that sponge to great use.

Sailing into the axis of the Stream, the water temperature climbed to 81 then dropped to 78 as we exited the southern edge, and with that, the ocean became even more tranquil and the air more tropical. The crew peeled down to shorts and shirts which is rare north of Bermuda in the fall. The plastic bags came off the Dorades and the vents were turned to face into the wind; hatches and portlights were opened. Even John was feeling better about life at sea.

There was a large clockwise rotating eddy along our rhumbline, which would help to propel us to Bermuda, or if approached on the wrong side, would slow us down. The weather router used a model, which placed the eddy to the east while PredictWind showed it to be to the west of the direct line to Bermuda. We would see whose Gulf Stream predictions were to prove most accurate.

Gulf Stream information is initially gathered by satellites. Various organizations collect the raw data and put it through programs like Global Real Time Ocean Forecast System (RTOFS) and HYCOM that analyze and work the information into a viewable and predictive format, which weather routers and PredictWind use. PredictWind will soon be using the Global RTOFS program. For real time satellite imagery of the Gulf Stream, Rutgers University Sea Surface Temperature, Daily Composite of East Coast and Northeast, analyzes satellite information and at times creates a three-day color composite that a navigator can print out and compare to other Gulf Stream sources.

Possibly because of cloud cover, Rutgers did not have the composite I needed for this passage. And that is part of the fun and planning for this passage, trying to outsmart the Gulf Stream and all its intricacies with whatever information that can be gathered and sifted. As it turned out, sailing the rhumbline took us into a one to two knot contrary current indicating the Global RTOFS, used by the weather router, was more accurate.

With each passing day, the lack of wind became more of an issue than a potential storm. The throttle to the Volvo Penta engine was set at the most economical 1,800 RPMs. On the third day out of Newport, suddenly, the engine RPMs oscillated and then the engine fell silent. The engine had run for far too few hours on the starboard tank to empty it. The fuel gauge sat on half full, not much different than when the tank was filled with fuel in Newport. Dave and I agreed we should dip the fuel tank to see the reality of the fuel level in that tank. Swans have a specific plug on top of the tanks and an aluminum dipstick for this purpose.

With each passing day, the lack of wind became more of an issue than a potential storm. The throttle to the Volvo Penta engine was set at the most economical 1,800 RPMs. On the third day out of Newport, suddenly, the engine RPMs oscillated and then the engine fell silent. The engine had run for far too few hours on the starboard tank to empty it. The fuel gauge sat on half full, not much different than when the tank was filled with fuel in Newport. Dave and I agreed we should dip the fuel tank to see the reality of the fuel level in that tank. Swans have a specific plug on top of the tanks and an aluminum dipstick for this purpose.

There was plenty of fuel in the tank. The remotely mounted Racor filter was only slightly discolored. We disassembled the fuel line connections and found no restrictions from the tank pickup to the Racor entry point. We had on our hands a mid-ocean mystery. Since the engine had run earlier in the day, without problems from the port tank, as an experiment, we swapped the equally new looking port Racor filter element with the starboard element. That got the engine running again. But as the engine RPMs were increased to 2,500 RPMs, the engine would again begin to cough.

There were no new Racor filters to be found on the boat. What we eventually realized is that the filters were only two micron. For this 100-horse power Volvo Penta engine, such a fine mesh with a moderate amount of contaminants was too restrictive for the fuel flow. However, by lowering the engine to 1,800 RPMs, we were getting by. Aurora was an untested boat, new to the charter fleet, with a growing “to do” list for the owner.

When the engine first died, we were in a real jam as we had already emptied the two jerry jugs of spare fuel into the tanks. We then needed a small reserve of fuel to top off the filter and bleed air from the fuel lines. “How will we get the fuel back out of the tank?” Dave asked. “People break out of prisons. We will have to think on it.”

When the engine first died, we were in a real jam as we had already emptied the two jerry jugs of spare fuel into the tanks. We then needed a small reserve of fuel to top off the filter and bleed air from the fuel lines. “How will we get the fuel back out of the tank?” Dave asked. “People break out of prisons. We will have to think on it.”

The owner of Aurora had put on board a cheesy looking, flashlight-battery operated, “Liquids Transfer Pump”. On the box it even said “As seen on TV”. The toy turned out to be a valuable tool. Removing five screws from a disk on the tank top gave us the clearance we needed for “As seen on TV” to do its job. From then on, we would always keep plenty of fuel in reserve for priming the engine.

We still had just over 100 miles to reach Bermuda and we were concerned that the quickly diminishing fuel supply would not last.The badly fouled prop was doubling fuel consumption. At all costs, we had to keep a reserve amount of fuel to motor around the extensive reefs surrounding the north and northeast approach into St. George’s. With no other option, we would squeeze the zephyrs and sail the distance even if it were no faster than one to three knots over the ground. But, like a good end to a thriller story, the wind did pick up from the east so we could sail at five knots.

With Marko, Chris, Keith, John and me on deck, visually picking our way through the white dots and blinking lights, set against a black background, Dave sat at the chartplotter below, making sure we were on a safe course. At 2100 Saturday night, on the fifth day after leaving Newport, we tied to the customs dock, in St. George’s, to find that all the officials had stayed late for us to clear in. They knew we were coming. What other country in the world could be as welcoming as Bermuda?

With Marko, Chris, Keith, John and me on deck, visually picking our way through the white dots and blinking lights, set against a black background, Dave sat at the chartplotter below, making sure we were on a safe course. At 2100 Saturday night, on the fifth day after leaving Newport, we tied to the customs dock, in St. George’s, to find that all the officials had stayed late for us to clear in. They knew we were coming. What other country in the world could be as welcoming as Bermuda?

Just around the corner, we tilted libations at the White Horse Tavern to celebrate our safe arrival and then slept soundly in a boat that did not budge, tied securely to the quay. In the morning, the crew had their first good view of the hill sides of St. George’s Harbor, full of colorful concrete buildings all with white tile roofs, as we motored the short distance to berth at the St. George’s Dinghy and Sports Club, where the rally festivities would take place that evening.

Bermuda has the most northerly reefs in the world and it seems more old forts per acre than anywhere else. One full day in Bermuda is not enough to be a respectable tourist, but the four-day delay in Newport left us little time to play. We wanted to stay on a schedule to meet our departing airplanes in St. Maarten. On Monday morning, we topped off the fuel and water at the Shell station and once again headed seaward through the narrow cut of St. George’s channel.

We motored right into a flat calm ocean. This certainly made John happy for he had decided to stick with us and complete the voyage. We were a diverse group like gears made from completely different metals, but all of us meshed and worked together and the absence of any one would have been sorely missed.

This was the time for the hand fishing lines to trail again off the stern. It did not take long to catch six dorado. They are far less bloody to deal with than tuna. We had no need to arrive in St.Maarten with more food than we departed Newport with so the hand lines were retired.

For a full day a 10-knot breeze shifted from the bow to a port beam reach. That was the chance everyone was hoping for. We struggled and fed the giant sausage containing the huge spinnaker out of the sail locker onto the foredeck. The sausage was hoisted to the top of the mast on the spinnaker halyard. Then the fiberglass collar was hoisted allowing the sock to free the spinnaker to balloon to a monster of a sail pulling us along at five knots. All day it kept us moving. In late afternoon, the wind shifted again onto a beat so the spinnaker came down.

All the crew were now competent with the workings and handling of Aurora. Even John had gained his footing and was moving easily with the rhythms of the boat, on deck and below. Each was fully competent to stand a lone watch. If needed, the captain is on call 24 hours a day for the slightest question. My bunk was in the aft cabin so it was always easy to call me by lifting a hatch in the cockpit. The new watch system became far more conducive to crew rest. Each crew, including the captain, would stand a 1.5 hour watch with 7.5 hours off.

All the crew were now competent with the workings and handling of Aurora. Even John had gained his footing and was moving easily with the rhythms of the boat, on deck and below. Each was fully competent to stand a lone watch. If needed, the captain is on call 24 hours a day for the slightest question. My bunk was in the aft cabin so it was always easy to call me by lifting a hatch in the cockpit. The new watch system became far more conducive to crew rest. Each crew, including the captain, would stand a 1.5 hour watch with 7.5 hours off.

The night watch south of Bermuda was quite different from the first leg. The moon had waned and the night, all night, was black. Even when there is a brilliant Milky Way of stars above, it does nothing to define a horizon or illuminate the deck. Barreling across an ocean, through the dark, one relies on Karma and odds, as visibility on the ocean past the bow, is simply a black void. There would be no way to see a floating container, a whale or anything else directly in our path, other than a lighted ship. But a watchstander soon gets used to the idea of spooks in the dark and there is no option but to continue on our way. To make the watch even easier, the autopilot now did the manual work so the lone crew only has to stay awake and watch for the lights of distant ships, monitor the radar and engine instruments.

Between motoring and slow sailing, we were chasing a seemingly unreachable horizon. As Chris said, “After the first half of this trip, my greatest emotion is boredom.” The tranquility gave Dave a perfect opportunity to refine his celestial navigation using “line of position” of the sun. He worked hard at teaching himself the process and finally found our position within a three mile accuracy plus a very accurate longitude from the noon sight. That is exemplary accuracy considering all the inherent deficiencies of a plastic sextant.

In the afternoon of our sixth day since leaving Bermuda Marko yelled “Land Ho!” We would not reach land in daylight instead we would be skirting a shore in the dark. Rather than going a circuitous route, we would shoot the narrow gap between Anguilla and Scrub Island, off the northeast coast of St. Maarten in the black of night. I have sailed the route many times but the crew had not. Airline pilot Dave was at the chart table below guiding us through, IFR, “instrument flight regulations”. “Dave, don’t let us hit anything.” I love adding a little pressure. I was on the helm watching the radar screen mounted over the binnacle. “Trust your instruments not your instincts” is the old aviator’s adage.

In the afternoon of our sixth day since leaving Bermuda Marko yelled “Land Ho!” We would not reach land in daylight instead we would be skirting a shore in the dark. Rather than going a circuitous route, we would shoot the narrow gap between Anguilla and Scrub Island, off the northeast coast of St. Maarten in the black of night. I have sailed the route many times but the crew had not. Airline pilot Dave was at the chart table below guiding us through, IFR, “instrument flight regulations”. “Dave, don’t let us hit anything.” I love adding a little pressure. I was on the helm watching the radar screen mounted over the binnacle. “Trust your instruments not your instincts” is the old aviator’s adage.

But the rest of the crew were incredulous and tense. They could see what was on the navigational screens but saw nothing but blackness where they knew land should be less than a mile away. Dave called up a course to jog us over, what amounts to a “base” course and line us up with the pass to be on our port beam before making a sharp turn to port to aim us straight for it on a final approach.

With that maneuver, the cockpit radar, which had been showing a solid wall of land features, then spit a dark crack which spread to a black space amongst the yellows and green returns of solid shore lines. Sailing under only a jib at five knots, we headed into the void. To everyone’s relief, especially Dave’s, nothing went bump against the keel. Out of the blackness, the twinkle of lights on St. Maarten, miles to our southwest, began to build and define not just shoreline but altitudes of a mountainous island.

The small southeast breeze helped blow us around to the west then the southern shore and into Simpson Bay just outside the bridge to the Lagoon. We anchored at 3:30 in the morning and switched on not only the anchor light, but deck lights to well illuminate our anchored ship against the backdrop of city lights. Then we fell to our bunks, exhausted from a long day and adrenalin crash after the heightened alertness required for coastal sailing at night. But we were all happy to have crossed an ocean, from north to south.

The small southeast breeze helped blow us around to the west then the southern shore and into Simpson Bay just outside the bridge to the Lagoon. We anchored at 3:30 in the morning and switched on not only the anchor light, but deck lights to well illuminate our anchored ship against the backdrop of city lights. Then we fell to our bunks, exhausted from a long day and adrenalin crash after the heightened alertness required for coastal sailing at night. But we were all happy to have crossed an ocean, from north to south.

Dave, Chris and Keith are all determined to return next November to sail again in the Offshore Swan Program. They want to shoot for a more serious high wind sailing experience. As Dave says, “I want to learn things I don’t know and can’t learn sailing in pleasant weather along the coast.” And Chris adds “I want to sail with different professional captains to see how they handle the same situations.” It won’t be long before Marco sails south on his own boat…..and John, he is staying put in his arm chair. I will be winging back to Malaysia to prepare my own boat for the crossing of the Indian Ocean, so this really just might be, my final last time, in the NARC rally.

Dave, Chris and Keith are all determined to return next November to sail again in the Offshore Swan Program. They want to shoot for a more serious high wind sailing experience. As Dave says, “I want to learn things I don’t know and can’t learn sailing in pleasant weather along the coast.” And Chris adds “I want to sail with different professional captains to see how they handle the same situations.” It won’t be long before Marco sails south on his own boat…..and John, he is staying put in his arm chair. I will be winging back to Malaysia to prepare my own boat for the crossing of the Indian Ocean, so this really just might be, my final last time, in the NARC rally.

For difficult to find “how to” boat maintenance videos, check out “Patrick Childress” on YouTube.