If you can’t find the pencil, you can’t draw the line (published March 2015)

There is a lot we learn from a first ocean passage that we wish we had known before we left. We will look at a few of these from the navigator’s perspective, and focus on those that might not be on the standard list of forethoughts. Some are personal preferences, with obvious options, others nuances. We raise the issues so you can think on your own solutions. The many declarative sentences are for the sake of brevity, not authority. Experienced sailors will have valid differences.

Navigation means knowing where you are on a chart and then choosing the best route to where you want to go. It is always the latter task that is the biggest challenge, meaning it requires the most knowledge and skill. This is especially true in the GPS age, but it was just as true when we only had celestial navigation to go by.

So we will talk about navigation and not even worry about where we are! We get that from the GPS, and if all the back-ups fail, we get out the sextant. We look instead at the broader picture of successful navigation of a sailboat in the typical environment we have at sea on an ocean passage. There are some differences between racing and cruising, but the basics are the same if you choose to get there in the most efficient manner, which includes of course just getting there at all if many things go wrong at once.

ACCURATE TIME

Dealing with that last thought first, it is important to know the correct time (UTC) at sea, because we can navigate to any port in the world with accurate time alone—we don’t even need a sextant—so it pays to wear an old fashioned watch and navigate by the time on that watch. Then maintain a chronometer log of the watch error from which we can confirm the rate of the watch, meaning how many seconds it gains or loses per day or week, and from that we can figure the right time by applying the ever increasing watch error on any date in the future. A typical inexpensive quartz watch has a rate of about 15s/month. Even if it costs $600 and is guaranteed 10s/year we need to check it. These specs are not always met.

You can check the watch with GPS as long as that is working, but to get started on a check without GPS, log on to www.time.gov and at the same time call 303-499-7111 to listen to the WWV time ticks to see if your computer and cellphone are correct. Also add that phone number to your address book and logbook. You can call it with a sat phone if that is all that is left. The importance of time for contingency navigation is covered in the book Emergency Navigation.

And most important, do not change time zones while underway. Choose the zone you want for ship’s time before you leave and stick with it until you arrive. Changing times underway, or changing anything on it, is just asking for trouble, even if everything is working properly.

NOTEBOOKS & LOGBOOKS

The more we rely on echarts and GPS, the higher the temptation to under-do good old fashioned written records. It is fundamental to good seamanship to keep a written record of your navigation. Use log readings if you have them, or speed and time, and course steered. Also, while all is working properly, record COG and SOG and GPS position, as well as wind info needed for sailing. More entries discussed later. Believe it or not, it also pays to record what tack or jibe you are on, though in most cases we should be able to figure that out—it depends on the wind and how well our records are kept.

There is a simple rule: make a logbook entry whenever anything changes. If nothing changes, make an entry every couple hours. The on-watch crew should generally make the entries, but you may find in the logbook only the navigator’s handwriting for the first half of the passage—until the value of this sinks in.

Also, maintain at least one other notebook for navigation notes. In this you record everything related to navigation that you compute or think about. Do not use scratch paper for any computation. A book with numbered cross-hatched pages is ideal, such as National Brand Computation Notebook, No. 43-648, because you can then plot various graphs right in the notebook.

You might even want a separate one for notes on weather and a place to record forecasts and related routing notes. This one should include a timetable of weather reports and forecasts. We have data from many sources, and they are valid at different times and then only available at certain times after that, and we need these times in UTC and in watch time, and we need a note of where we get each one, which may include radio or fax channel information. This is a very important schedule, which takes some time to prepare, and is easier done before departure. In any event, you will have it made by the time you arrive, but you may have missed a couple reports in the process. The times of GRIB file updates as well as latest weather map broadcasts and voice reports can be sorted out at home.

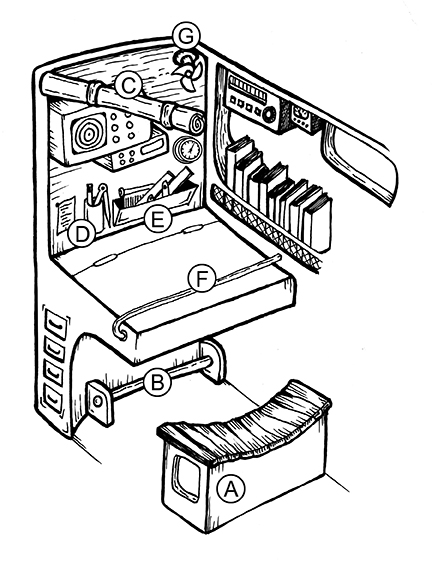

CHART TABLE & PLOTTING TOOLS

The value of pencil and tools holders outside of the chart table cannot be over emphasized. If you can’t find a pencil you can’t draw a line that could be crucial. The chart table itself is essentially useless space as it is too convenient a place for everyone to stash things. Unless it is built in, we also need to devise a way to protect the laptop used for navigation. It has to be fixed so it cannot slide around or bounce off the table and include some quick way to cover it to protect it from water when you are not there. The most vulnerable parts might be the connectors to it: power cable, USB and serial connectors. I have seen a person fall across the cabin in rough conditions and reach out to brace the fall and hit just the right place to break off the only serial connector of an otherwise bulletproof laptop.

A laptop stand that is raised a couple inches from the chart table is handy, so you can lay out plotting sheets or charts underneath it.

Practice with your night-lights. A hand-held (teeth-held) light or head lamp is often a good solution. We need to see, but we cannot let any light out of the nav station. There is no virtue to red light; it is the brightness that matters; a dim white light is better than red, and it does not distort chart colors. I would always keep one AA flashlight in the pencil holder as well, because just like the pencil, there are times you must have one. Depending on your eye sight, you might want a magnifying glass in there as well to read small print on instrument specs, dials of a barometer, or while checking the shoreline route on a chart—it would be a rare ocean voyage that does not have shoreline issues either leaving or arriving.

And you will need a way to lock yourself in place. A well-designed footstool that lets you brace your knees under the table is one, or a seat belt could do it. Another useful trick is a tight bungee cord stretched across the chart table near where you lift the lid. This holds the lid down in a broach (a safety requirement) and it holds charts and books in place in a seaway. It is not at all hard to work around during chart plotting. You can just pull the cord down over the lip to get into the table—i.e. to hand someone their sunglasses.

Several highlight markers and colored sharpies are useful, as are a pack of large rubber bands for organizing things. Blue painter’s tape is an excellent way to label things and use as Post-its for reminders. Headphones for the radios let you communicate at night and listen to weather reports without waking folks up whose sleep could be crucial. If you are sailing in the tropics, try to rig a fan for the nav station. A pad of universal plotting sheets is helpful for weather routing, the old fashioned way.

SHARE NAV & RADIO INFO

Teach the SSB radio and sat phone usage to all of the crew. SSB transceivers can be complex, so posting a cheat sheet on how to use it is valuable. Even modern VHF radios might call for a note or two.

In the ideal world, you would have at least one person on each watch who is in tune with the navigation. That would mean knowing how to use the echart program and be aware of latest goals, weather tactics and possible hazards. They can also encourage logbook participation. On larger racing boats the crew can get departmentalized and important navigation information is not shared enough to be as safe and effective as it might be.

One way to help with this is to post a small-scale chart showing the full ocean route that is readily in view to all crew. Then plot and date your position once a day. The crew will get more interested in the navigation and indeed know where you are along the course. Discussing at any common meal times the latest weather forecasts and tactics can help as well. On a tight watch system this might not happen very often, so the navigator’s helpers can fill in.

Also in this same vein, use some modern version of a route box in sight of the helm and deck crew. This could be just several strips of blue tape on which you write in big letters with a Sharpie the present course to steer. Or you could make something more elegant. The main idea, though, is to have a list of these courses, not just a white board where you post only the active course. We want to see the old course crossed out, and the new course written below it. This keeps all in tune with what is going on with the course over time.

Having the active course in view gives the helmsman a quick reference on what to come back to when thrown off course for any reason. Memory could hurt us if we had been on 220 for two days but now the course is 200. Also we could get confused if the course was 200 then 210 but now it is back to 200.

SAIL WAYPOINTS

SAIL WAYPOINTS

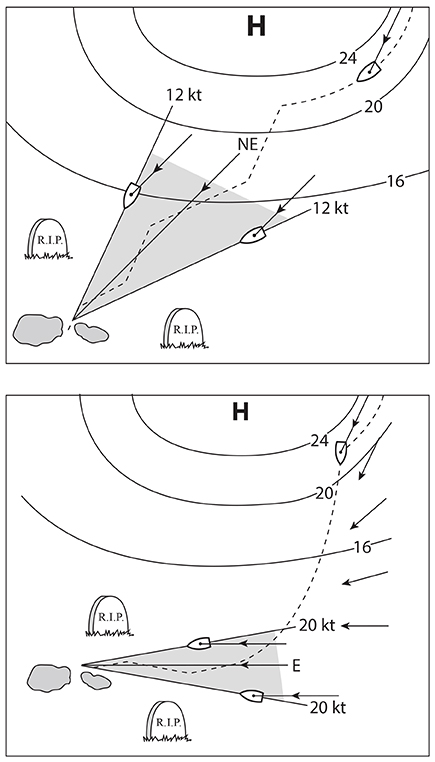

If we are not sailing to specific waypoints we are not navigating; we are just out sailing. Even on an ocean passage we need waypoints. There is essentially no efficient ocean crossing that has just one waypoint at the destination. Needless to say we want one there, and we should always keep an eye on the VMG to that one, but there will be intermediate ones we set and change as we proceed, and the immediate navigation is to maximize VMG to that active waypoint.

Sailing around the corner of the Pacific High, for example, you might use some guideline to mark the corner such as two full isobars off the central high pressure. This choice depends on how far you are from that point. If you have a three or four day forecast of the winds that might let you cut it a bit closer, then you can try that. But the main job is to set one and optimize speed to it until you have good reason to move it. The forecast might change and call for heading more south toward the trades for a while, or let you sail a bit closer to the rhumb line.

Once around the corner, you might set another waypoint based on the forecast of the trade winds closer to your destination. In other words, with the present forecast of the trades out to 800 miles, you might choose the point that sets you up for your best wind angles if you were at that point and the trades did indeed stay as forecasted in speed and direction. Then you again watch that and adjust as needed. Both the speed and the direction of the trades could cause the waypoint to shift.

When sailing waypoints in this manner, sometimes the course is crucial—that is, if we do not make that waypoint we could lose a lot of efficiency, so we have to fight to make it. In this case the navigators job is to stress this point and also keep a more careful watch on what is actually being steered and recorded in the logbook. With all the electronics working, we have an exact trail on the echart of what we are making good, so if we are not making it, we need to study the situation to find out why and try to correct it. Not to sound too crass, but you may have one watch that just wants to go fast, so they are reaching a little extra all the time and not looking ahead to the consequences. Again, we are back to getting the crew involved with the navigation.

On the other hand, there can be circumstances when you have a lot more freedom and you can simply say go as fast as you can (with present sails set), always looking ahead to see if a crucial waypoint might be developing.

STAY ON THE RIGHT JIBE

This may sound obvious, but in a long ocean race or voyage it might slip by us, especially in wonderful sailing conditions. Thus the task of a continual monitoring of the VMG to the next waypoint is crucial. It is also crucial to monitor this progress on both jibes. It could be the time to jibe is affected by the sea state, because in the same wind, one jibe is much better than the other because of the direction of the waves. This could take some testing; the interaction of wind and waves can be unique.

Depending on the boat and crew and sailing conditions, the decision could also be affected by how you want to spend the night. It could also be a time to decide, depending on where you are relative to the waypoint you want, if it might be valuable to set a head sail over night. If your route calls for fairly close reaching at the moment, it could be that the extra progress to weather could balance out a slower speed and reduced risk of sail trouble for the overnight run.

One way to make a quick estimate of the consequences of steering the wrong course is what we call the Small Angle Rule. Namely a 6º right triangle has sides in proportion of 1:10. Thus if I sail the wrong course by 6º for 100 miles, I will be 10 miles off my intended track. The rule can be scaled up to 18º and down to 1º. It can also be used to estimate current set and other applications.

EVALUATING THE FORECASTS

We set the waypoints based on the forecasts, so it is important to remember that there will always be a forecast, and they are not marked good or bad. (Eventually we will get more probability forecasting into marine weather, but for now this evaluation is up to us.)

One obvious way to evaluate the forecasts is to see if the present surface analysis agrees with our own observations. To do this, we need calibrated wind instruments (to compute true wind speed and direction) and a good barometer. Then we plot our position on the weather map, read off wind speed and direction and pressure and compare to what we have recorded for these at the valid map time. If they agree, we have more confidence in the forecast. To the extent they do not, we have less confidence.

There are also well known properties of the winds aloft at 500 mb that tell us if the surface forecast might be strong or weak. These depend on the flow pattern and speed of the winds, as well as the shape and location of the surface patterns below them. Guidelines for these procedures are in Modern Marine Weather (Starpath Publications).

If we have surface forecast conditions that are very enticing for making a bold move, but our evaluation of the forecast is weak, then we should be cautious. You might then do just half of what you want to do, or do it for just half as long, then wait till you get another map (six hours) to see how things are panning out.

Another simple and important guideline is to not rely on just the ubiquitous GRIB formatted GFS model output. The minimum to do is download the actual weather maps produced by the Ocean Prediction Center and use them as an important criteria in evaluating the GRIB data. Once the GRIB maps are confirmed, then you can have more confidence in using their extremely convenient format. The first map in a GRIB forecast sequence will usually coincide with the latest synoptic time of the OPC surface analysis. As noted earlier, making a weather services timetable is crucial to putting this together.

A unique new Kindle ebook by Will Oxley called Modern Racing Navigation discusses the latest technology available to the navigator.

David Burch is the director of Starpath School of Navigation, which offers online courses in marine navigation and weather at www.starpath.com. He has written eight books on navigation and received the Institute of Navigation’s Superior Achievement Award for outstanding performance as a practicing navigator.