Sometimes all the preparation of getting ready to go cruising makes my head hurt but never more so than when it came time to replace/upgrade our rescue electronics (published February 2016)

So much has changed over the years. Devices are smaller, smarter, and there are just plain more types of rescue electronic devices. Used to be easy; just buy an EPIRB, register it, and go. Now you can choose between EPIRBs, PLBs, and MOB beacons (a special sub-set of PLBs). Do you need them all? Just one? Where is the “all-in-one” device? Well my headache is over… here is what I learned.

The first question to ask is “How quickly will you be rescued?” Or perhaps, more functionally, “How quickly would you like to be rescued?” The answer to those questions goes to “Who will be doing the rescuing?” There are really two sorts of rescue situations: 1) Those aided by search and rescue (SAR) organizations—Let’s call these “SAR rescues”. These by nature will take longer; and 2) Those conducted by your boat or other boats presently in your vicinity—these are man overboard situations—“MOB recovery”—These by nature must happen quickly as long term exposure is the greatest risk to loss of life. This is where the real revolution in rescue electronics has occurred.

SAR RESCUES

If your boat is sinking, you need someone to come and get you. While SAR resources can be alerted quickly by VHF, SSB, EPIRB, or PLB, your distance from shore and from the rescuers will determine how long it takes for them to get to you. Helicopters can only fly so far before having to turn around due to lack of fuel. Getting a boat to you can take days if you are far enough away from shore or from shipping lanes. Herein lies the essence of the choice between an EPIRB and a PLB. Both will signal the SAR organizations exactly the same way, via 406 MHz satellite relay, and all modern devices will provide your exact location via GPS. PLBs cost less than EPIRBs. The primary reason is battery life. EPIRBs must be able to transmit continuously for at least 48 hours. PLBs tend to be smaller and their batteries are designed to transmit for about 24 hours. Both will provide 121.5 MHz homing signals which are used for near distance, or “final” location.

With offshore ambitions, I still wondered why anyone would want a PLB instead of an EPIRB. EPIRBs are registered to the boat whereas PLBs are registered to the person. If you are crewing on others’ boats, a PLB may be a part of the kit of gear you bring with you. Reality is of course that there are many more boats plying near-shore waters than going out of sight of land for extended periods of time. Near shore, the PLB is a great device and the EPIRB may be overkill. Kayakers, hikers, and fishermen will appreciate the small (“P” is for “personal”) size of the PLB. Following the loss of two young men, a bill was introduced in the Florida legislature which if passed would offer a 25 percent discount on annual boat registration fees for boats carrying registered PLBs or EPIRBs. Discount or no discount, they still make sense.

SELECTING AN EPIRB

First one has to cut through a little lingo: Cat I and Cat II. Cat I EPIRBs can self-deploy using a hydrostatic release, which if they sink 1.5 to 4 meters below the water, ejects the EPIRB from its case and actives it—handy in the case of a ship going down quickly. The hydrostatic releases must be replaced every two years. Cat II EPIRBs are manually deployed. One grabs the unit out of its mounting bracket and presses a covered button to activate it. Cat II is most widely used by sailors. Both Cat I and Cat II units activate when placed in water.

It used to be that one had to also select between EPIRBs with or without GPS. Without GPS, a 406 MHz location narrowed the search down to about 28 square miles. With GPS, that figure is 0.03 square miles. No wonder all new units have GPS.

There are two really big names in the EPIRB business: McMurdo and ACR. McMurdo also makes a lot of the electronic systems behind the scenes that receives and processes EPIRB transmissions for SAR organizations and is a force in commercial marine safety. ACR has been making emergency signaling devices for mariners and others for over 58 years. In 2015, ACR acquired British upstart and very innovative Ocean Signal. Ocean Signal’s products deserve some study.

TOTAL COST OF OWNERSHIP

EPIRBs have long-life, high-capacity lithium ion batteries. These must be protected from water, especially salt water so the EPIRBs are carefully sealed and those seals are pressure tested by the manufacturer. This means that when the batteries reach their end of life they must be replaced by a service center which then recertifies the water tightness of the EPIRB. This is an expensive process with battery replacement typically costing around $300. Having an EPIRB with a longer battery shelf-life means fewer of these replacements.

Enter the tiny Ocean Signal EPIRB1 with 10 year battery replacement interval (battery life if not used other than for periodic tests). This is currently unique in the industry with most other EPIRBs having six year battery replacement intervals. And this unit is tiny, about 30 percent smaller than other EPIRBs, and has a tiny bracket so it is easy to find a convenient and safe place to mount it.

The running time of the EPIRB1 is at least 48 hours as required for EPIRBs. For even longer running time, Ocean Signal offers another product unique in the market, their E100 and E100G, with 96 hour operation. The batteries of this unit must be replaced every five years but they are user replaceable avoiding the cost and out-of-service time of having to return the unit to a service center.

CREW OVERBOARD

As we prepared to go cruising, our non-sailing friends often asked Jill or me if we were afraid. We told them “No, we have trained and practiced a long time for this.” Truth is we have for years been terrified of the possibility of coming on watch one night to find the other one has fallen off the boat in strict disobedience of our standing orders, “stay on the boat and don’t run into anything”. Imagine that situation… How long ago might the other have left the boat? How far back do you go? How do you compensate for drift when navigating your reciprocal course?

Over the last few years McMurdo has offered two small MOB beacons which transmit AIS signals to provide the location of the MOB. The SmartFind S10 is manually activated and waterproof to 60 meters making it ideal to be carried by SCUBA divers. The SmartFind S20 is designed to be mounted in an inflatable lifejacket and is automatically activated when the PFD inflates. (A list of tested/authorized lifejackets can be found at www.Mcmurdogroup.com). There is a standardized range of MMSI numbers reserved for SAR devices and a standardized set of AIS messages dedicated to SAR devices, such as MOB beacons. The McMurdo devices were the first on the market to utilize these tools. AIS receivers have evolved to become “smarter” to these signals and to provide alarms when one is received. If your AIS receiver or MFD does not provide this alarm, you can add the Digital Yacht AIS Life Guard black box which listens to your NMEA 2000 bus and can trigger a buzzer, horn, bell, or other device to alert crew. The Vesper XB-8000 and other of their AIS systems also have external alarm outputs that respond to the receiving of AIS MOB messages.

Here again, Ocean Signal has innovated further with an even smaller device that works with all inflatable lifejackets and has one extra feature— alert via DSC to your boat’s VHF radio. Keeping in mind that as the time until the alert of crew increases, the further the boat will be from the person in the water, a DSC call cuts the alert time significantly. An AIS message which requires the location data. It takes about a minute or so once activated for an MOB beacon to find its location via GPS before it can transmit. While the AIS signal will be received by all boats, the Ocean Signal MOB1 quickly sends an alert to your boat using DSC calling which sounds an alarm on your VHF radio (with DSC). On our Icom IC-M506 this alert will raise the dead with a very loud alarm and bright flashing screen.

MATCHING THE MOB BEACON TO YOUR BOAT

The MOB1 has a very clever interface to program your boat’s unique MMSI number into its memory. Using a cell phone, tablet, or PC, one runs an app which asks for your MMSI. You then hold the MOB1 up to a pulsing bright square on the screen of the phone, tablet, or PC and the MOB1 is programmed. If you are crewing on different boats, you can easily reprogram or deprogram the MOB1 as you move on to or off of other boats.

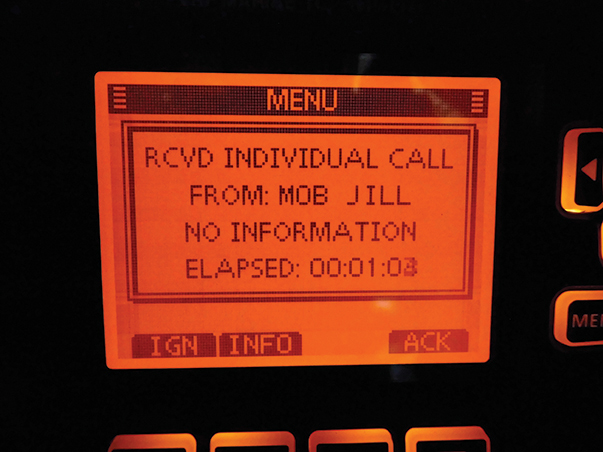

By entering the MMSI of the MOB1 itself into your VHF radio, the radio will identify the beacon by name, for example, “MOB JILL” —a message I never want to see on the radio display but one that would not be at all ambiguous.

We installed one of these in each of our PFDs and conducted a test. Jill motored away in the dinghy and activated the unit. Seconds later our VHF radio was all ablaze with the alert “RCVD distress relay from: MOB Jill man overboard”. No questions about what was going on. Shortly after I silenced that alarm, our B&G Zeus2 MFD sounded an alarm and displayed: “Man Overboard—AIS SAR Activated” and offered the option to “Activate MOB” which placed an MOB waypoint on the screen and began the navigation back to that point. As Jill moved, the target moved, just as any other AIS target would be tracked on the MFD.

ALL IN ONE?

One could ask, as I did, “Why not an all-in-one device—you know, EPIRB, 406 MHz, 121.5 MHz, AIS, DSC, Personal and Boat device?” There are several reasons why not.First, the morass of various countries’ radio frequency device registration processes make it unlikely for there to be a single device with the ability to broadcast all of the necessary frequencies. Second, the tradeoff between the small size desired for a MOB beacon and the larger size needed for the battery life required for an EPIRB run juxtaposed. Third, an EPIRB is required to activate automatically, when in the water. A device carried on one’s person needs to be immune to getting wet. Fourth, the EPIRB is a device registered to the boat. The MOB beacon is not registered and a PLB is registered to the person. Both can move from boat to boat, and there will likely be multiple of them on a given boat. So for the foreseeable future anyway, one can expect the ocean-bound sailboat to need both an EPIRB and MOB AIS beacons.

NOT AFRAID

More equipment on board that we hope to never use. With the new EPIRB on board we know we can summon help if ever needed. And after testing the MOB1 with our VHF radio, AIS transponder, and MFD, we are convinced the combination of DSC and AIS will alert us immediately to a man overboard and will allow the other of us to get the boat quickly back to the person in the water. So, now in answer to that question our non-sailing friends ask, “We are not afraid—have lots of respect for the sea yes—but not afraid”.

Over the last several years we have watched Pete and Jill Dubler’s restoration and refit of their Pearson 424. In December 2015, they began their new life as cruisers aboard S/V Regina Oceani.