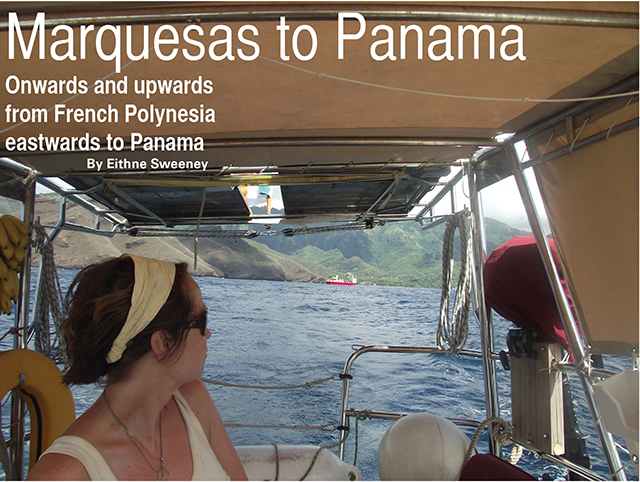

Onwards and upwards from French Polynesia eastwards to Panama (published March 2014)

Last Christmas we had no ordinary wishlist from the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Tasked with sailing our boat eastward from the Marquesas to Panama, we asked Santa for a little help. A 15 to 20 knot southerly or westerly wind and a one to two knot east-setting current both made the list. So too did a few extra gallons of diesel.

Christmas at sea was always going to be emotional. For weeks we had been thinking of family and friends coming together to celebrate the day in Ireland and New Zealand, pining for all the food, drink and conversation that we would miss out on. It didn’t help matters that our forestay had just broken 2,000 miles from land and we were dubious about how far we would make it with a limited amount of diesel. Christmas Day loomed like a big mountain that we had to master before we could mentally get back to our adventure.

A ROUTE LESS TRAVELED

Our route was neither traditional or typical. The few sailors who do cross the Pacific from west to east each year usually take the southerly route from French Polynesia, passing by Pitcairn and Easter Island before riding the Humboldt Current along the Chilean coast to the Galapagos Islands. This had been our original plan but a cold, windy wintry passage from New Zealand to Tahiti changed that. The First Mate made a stand and refused to enter latitudes of greater than 30 degrees for the year ahead and in any case, the Skipper wasn’t too keen on donning the winter woollies so soon again either.

So we started looking at alternatives. We considered abandoning our original plan of reaching Ireland. From French Polynesia, we could head north to Hawaii and perhaps on to the mainland U.S. or indeed come back south after cyclone season and spend our year cruising the Pacific. Or we could stay in French Polynesia itself, pottering around the many islands and returning to New Zealand via Tonga and Fiji. There was also an alternative route to Panama—from the Marquesas Islands, head north-northeast until approximately 5 degrees north and then turn to travel east for 3,500 miles.

We first read about the Panama route in Jimmy Cornell’s World’s Cruising Routes and it didn’t get a favorable mention—4,300 miles in light easterly winds while flirting with the ITCZ. Sailors were advised to stock up on fuel and supplies, and focus on using the equatorial counter current to gain whatever easting they could. It was tempting and it meant we might just make our end destination as planned after all. The first third of this route is the same as the route to Hawaii so we whittled the options down to two. Depending on how the first 10 days went, we would turn left for Hawaii or right for a long haul to Panama. If we did make it to Panama, we would again be one of a handful of boats who make the trip each year, ‘en l’envers’ (in reverse) as the locals call it.

FROM POLYNESIA TO PANAMA

Leaving Nuku Hiva in late November, we sailed due north until we reached 5 degrees north. The wind was steady at a comfortable 15 to 20 knots, the sea was slight and the sky was clear. Ashling was sailing well, and the sea and sky conditions were putting minimal stress on her rig so the crew was sleeping easy. Ten days in, we crossed the equator, boosting crew morale as we ticked off another milestone on our adventure. The Northern Hemisphere never looked as good.

Then we changed course and headed due east towards Panama, sandwiched between the unsettled weather of the ITCZ above and the south equatorial current below. From here, some days were better than others, but in general, progress was slow.

We had the occasional becalmed day when we were either on the engine or heading back to where we had come from in search of wind. Heading back the way we had come was mentally frustrating as it felt like all our hard work to move forward had been for nothing. Typically we would travel more than 100 miles per day but on average only 57 miles of this was towards Panama. On the worst day we gained just 10 miles!

Motoring on calm days took its toll on the Skipper who was eyeing the fuel gauge every minute. We can catch water from the sky and we can generate electricity from wind or water. However, fuel was the one thing we couldn’t replenish at sea and every hour on the engine in the first half of our passage added another line to the Skipper’s handsome face.

CHRISTMAS AT SEA

To our surprise, Christmas Day on board turned out to be quite a pleasant experience. We checked our daily distance progress and found a weekly peak of 89 miles covered towards Panama over the previous 24 hours. After a few days of mediocre progress and reduced speed due to our new rig and sail settings, it appeared that Santa had indeed received our wishlist.

To our surprise, Christmas Day on board turned out to be quite a pleasant experience. We checked our daily distance progress and found a weekly peak of 89 miles covered towards Panama over the previous 24 hours. After a few days of mediocre progress and reduced speed due to our new rig and sail settings, it appeared that Santa had indeed received our wishlist.

And that was only the start of his delivery. By mid-morning the sun had appeared from behind the clouds to treat us to a spectacular day. We picked up an east-setting current and found some healthy 15 knot southerly winds. We cracked open a bottle of New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc and relaxed in the warm sunshine, munching on snacks and goodies, and leaving the sailing to Ashling who was in her sweet spot, sailing at five knots due east.

While there was just the three of us out there for Christmas, we certainly didn’t feel lonely. After phone calls to friends and family, we exchanged some unique Christmas presents that had been purchased in the limited stores of our last port, including a bar of soap, a Sudoku puzzle book and a Cadbury’s Crunchie. We ate Christmas dinner watching a glorious sunset behind us, and turned around to find a full moon rising in a cloudless sky ahead. It had been an unexpected but much welcomed day off and all things considered, we couldn’t have wished for a better day.

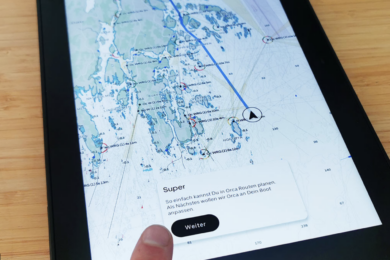

And the New Year brought even more gifts. Even without our full headsail, we went from strength to strength with daily distances covered, reaching a record 127 miles one day. Every midday status check produced beaming smiles as our prayers were answered and the little boat icon on our chart plotter inched its way another degree closer to land. In southerly and sometimes southwesterly winds, Ashling powered along, eating up the miles under minimal strain. And as if that wasn’t good enough, we also picked up a super current, stepping onto a magic carpet that boosted our speed by two to two and a half knots.

ONE FINAL…

It all seemed too good to be true, and unfortunately it was. Even after traveling some 5,000 nautical miles—3,800 as the crow flies—over seven weeks, the Pacific Ocean had one final surprise in store.

The Gulf of Panama is known for its light winds so it was no surprise that we could not sail for the final approach to land. On Day 52, we were motoring along through calm waters when the trusty Perkins 4-108 gave a few coughs and died. The fuel gauge showed plenty left in the tank so the Skipper got out his tools, rolled up his sleeves and looked for the problem. Cables—check, connections—check, filters—check, water—check. Everything seemed to be in order so he opened the tank to see if there was a fuel or air lock. The good news was that there was no blockage or air lock. The bad news: there was no fuel left. So much for trusting the fuel gauge.

So when we can’t sail and we can’t motor, we drift with the current, which, thankfully, was bringing us towards land. We contacted the Panamanian Coast Guard to let them know about our situation and then sat back and waited, hoping that our pigeon Spanish had communicated the right message. The Coast Guard’s English was as good as our Spanish so it took a few emails for each of us to decipher what was happening. Thank goodness for satellite phones and translate.com.

Apart from the reduced speed, all else was good on board. We had plenty of food, water and gas to get us through another week at least. The sun was shining in a clear, blue sky and the flat, calm sea was putting minimal strain on Ashling. Our spirits had taken a kicking and we dug deep to find the last ounce of patience that we didn’t think we had. But we could see land, we could even smell it and we just needed to wait a few more days to touch it.

LAND AT LAST

Two days later we finally drifted into Panamanian waters and it was all stations go. A Panamanian Aeronaval patrol boat appeared on the horizon and wide-eyed, not daring to believe what we were seeing, we pinched ourselves to make sure it was real. We only really did believe it when the VHF radio crackled to life and a naval officer announced that they would reach us in five minutes.

We scurried around setting up lines and fenders, not knowing what was about to happen but trying to prepare for every scenario. Would they give us fuel? Would they tow us to land? Would they come on board and search the boat to make sure that we weren’t some Colombian banditos trying to pull a fast one?

Thankfully they had an English speaker on board so the First Mate got busy on the VHF and the next thing we knew, we were being towed for the final 25 miles back to land. At eight knots per hour, the Aeronaval’s skipper was struggling to keep the engine going at minimum speed and Ashling was struggling to keep up with speeds she has never seen before, even in the best or worst of weather conditions. Eventually we arrived at the secluded bay of Ensenada Naranjo in the northwest of Panama just after sunset.

The next morning the Skipper went ashore with the Navy crew to buy fuel and do a supermarket trolley-dash, running around the Super 99 in Santiago like a madman, grabbing items at random from the shelves—bread, beef, beer and Betty Crocker’s Instant Chocolate Cake mix. Forget Coca Cola, Betty C is your woman for globalization! They returned a few hours later to fill up our fuel tank and check that everything was working as it should before leaving us to a sunny afternoon alone in the anchorage.

Words could not describe how we felt. In the space of 24 hours, our lives had changed utterly. One minute we had resigned ourselves to another week at sea and the next minute we were at anchor, surrounded by trees, birds and land. It took a few days, and more than a few beers, to fully come to terms with it all but relief, elation and bewilderment make a good start at describing our mental state. We cannot thank the Panamanian Coast Guard/Navy enough. They were professional and organized in everything they did for us, even when at first they thought we were some silly kids who had run out of fuel after only a few days of sailing down the coast from Mexico. Once they realized that they were the first people we had seen in 54 days, their stunned faces showed that they had suddenly revised their opinion of us.

Eithne Sweeney and her husband Myles took the route less traveled to sail east from New Zealand to Ireland in their Endurance 35 Ashling. Last November they traveled the longest leg of their journey, eastwards from French Polynesia to Panama. Myles and Eithne arrived in Ireland in July 2013 after sailing over 15,000 miles from New Zealand via the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Read more about their sailing adventure at http://sweenaghansatsea.blogspot.co.nz.