The southern Indian Ocean has a nasty reputation for strong winds, large seas and quickly changing weather systems (published October 2015)

At a chandlery in Langkawi, an island off the coast of northwest Malaysia, we found a stack of second-hand jibs and mainsails in a corner. The owner said he sold them to cruisers crossing the Indian Ocean who didn’t want to shred theirs, or who wanted a spare in the event that they did shred theirs. These types of comments kept piling up as we turned our attention to the next leg of our slow circumnavigation, the passage from the Sunda Strait in Indonesia to South Africa.

At a chandlery in Langkawi, an island off the coast of northwest Malaysia, we found a stack of second-hand jibs and mainsails in a corner. The owner said he sold them to cruisers crossing the Indian Ocean who didn’t want to shred theirs, or who wanted a spare in the event that they did shred theirs. These types of comments kept piling up as we turned our attention to the next leg of our slow circumnavigation, the passage from the Sunda Strait in Indonesia to South Africa.

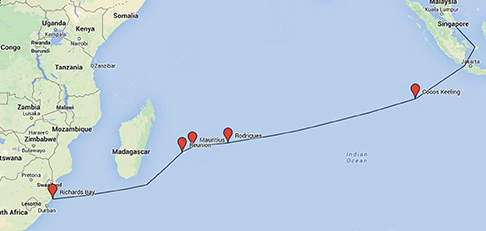

As the saying goes, “We may be dumb, but we aren’t stupid.” We picked this route for a number of reasons. First, it avoids the zone bounded by 10 degrees south and 078 degrees east where the piracy threat is still very real, particularly for easy targets like us now that commercial ships have adopted aggressive security measures. A boat we know had actually contacted a security company about going up the Red Sea. The company said they would put two heavily armed men on your boat for a not inconsiderable cost. However, they required ten boats to go in convoy. Last we heard there were no takers.

Secondly, we wanted to have plenty of time to explore Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand and do some land travel during our year in this region. A popular alternate route to South Africa skirts the pirate box by way of Sri Lanka, Chagos, Madagascar and the Mozambique Channel. This did not appeal because it would have meant leaving Thailand in January to catch the right weather and missing our land travel plans.

Finally, our route would take us to Cocos Keeling, Rodrigues, Mauritius and Réunion, all of which had been highlights of friends’ circumnavigations. And besides, by now we should be used to long passages and a little heavy weather sailing, right?

We left Thailand in February and headed back south, our second (and thankfully last) trip through the either windless or squally, busy and lightning-prone Malacca Strait. We had a long list of boat projects and began to chip away at them as we went along. In Phuket we had our dodger and bimini re-stitched for the umpteenth time. It’s amazing what a short life span these things have in the tropics.

We also decided to have a new mainsail made. Although our Quantum main was only seven years old, the cloth had begun to disintegrate. Our friend, Jamie Gifford on Totem, a Stevens 47, put us in touch with a young Kiwi sailmaker who was cruising in the area. Together they designed a new main with all the bells and whistles we wanted—triple-stitched seams, full length battens with chafe protection, Tenara thread and three reefs among them—for less than the cost of our old main. Three weeks later our Lyttelton sail, built at the China Sail Factory, was delivered to us in Malaysia—probably the nicest sail buying experience we have ever had and the quality looks to be top-notch.

We headed for Puteri Harbour near Singapore, a new Malaysian marina which is cheaper and more modern than either Raffles or the Republic of Singapore Yacht Club. Kite would be safe there while we traveled through Southeast Asia and Japan for almost two months. We got back to Puteri on June 10 and began to tackle in earnest our boat projects to get Kite ready for the Indian Ocean. We were with our good friends Jake and Jackie Adams on Hokule’a, a Liberty 46, Roger Block and Amy Jordan on Shango, a Pacific Seacraft 40 and Bill Babington, a single-hander on Solstice, also a Liberty 46. It was almost festive as we each went through our boats from stem to stern with a well-earned happy hour at the end of the day. Shango took off first. Finally on July 27, Hokule’a and Kite also headed south to Indonesia. Unfortunately, Bill ran into problems and, in the end, decided to cross the Indian Ocean the following year, a big disappointment for us.

Our trip south was dead into the prevailing southeasterlies which meant a lot of motoring or motor-sailing and at times made the 650-mile trip a real slog. Happily, the GRIBs were pretty accurate and we were mostly able to pick periods with light winds to make our hops. Indonesia is a favorite and we were feeling nostalgic as we passed through. It was our last taste of this part of the world. In the Sunda Strait, between Java and Sumatra, we anchored for a night in the old caldera of Krakatoa, the massive volcano that blew apart in 1883 with the loudest bang ever recorded on earth. It was a little eerie, particularly since a new active volcano, Anak Krakatoa (“child of Krakatoa”), sits growing and smoking in the middle. The volcano didn’t erupt on top of us, but we did almost get nailed by a big and very scary waterspout!

Hokule’a, Kite and Shango were now together at the Ujung Kulon National Park at the entrance to the Sunda Strait. The day before we were to leave for Cocos, Shango radioed that their house battery bank had died. This was a serious issue since it was uncertain whether anything could be done about it in Cocos, 600 nautical miles away, and Mauritius was almost 3,000 open ocean miles ahead. Indonesia’s labyrinth of arcane and ever-changing rules makes it nearly impossible to import anything. All this meant Shango would probably have to backtrack to Singapore and might be forced to delay their Indian Ocean passage to next year. Like Kite, Shango is a 12-volt boat with solar panels and a Monitor windvane. They elected to continue on, so off we all went with a pretty good weather forecast. Along the way, we found in our stash of tourist literature a phone number for a local shipping company in Perth, Australia that supplies Cocos and radioed the information to Shango. Roger was then able to arrange, via sat phone, the purchase of a replacement battery bank which arrived in Cocos three days after we did. Pretty amazing, and very good luck for Shango.

Our second day out we heard a loud thunk in the cockpit and discovered that our towed water generator was gone, torn right out of its mount on the stern and the safety line had snapped. We figured a very large fish had struck it. “Ham” (it was made by Hamilton Ferris) had been with us since we left the Caribbean. We considered it a key piece of equipment which made us energy self-sufficient without any need to rely on the engine. We don’t have a generator, so this was a major bummer and we were unable to duplicate Shango’s luck. Ferris Power Products didn’t have any units in stock and apparently wouldn’t for several months.

After four days of good tradewind sailing, we reached Cocos Keeling, a beautiful atoll in the middle of nowhere. We had to slow down the last day so we would arrive in daylight as the entrance channel through the reefs is a bit tricky. Cocos was originally “owned” by a Scottish family who developed a copra plantation and brought in Malay laborers to work it. Since 1955, Cocos has been a part of Australia. It is the site of Australia’s first naval victory in 1914 when the German cruiser Emden was sunk here.

The Malay community lives on Home Island, where jobs are scarce and the Australian government provides generous support. It was a bit funny to see Malay villagers in conservative Muslim dress with their “g’day mate” Aussie accents. The few non-Malay Australians and tourist operations are on West Island, across the choppy lagoon. The tradewinds never seem to stop blowing here at a good 20 to 30-knot clip and we took a ferry across the lagoon rather than make the long trip by dinghy from our anchorage at Direction Island.

We spent five days at Cocos exploring the islands and reefs including the “Rip”, a fast drift snorkel with lots of sharks, turtles and fish zipping by. The azure water is crystal clear, like parts of the Bahamas or the Tuamotus. Many people spend weeks here and we could have also, but a good weather window for our next leg to Rodrigues Island popped up and we thought we had better grab it.

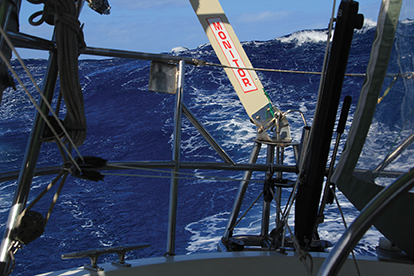

Rodrigues lies east of Madagascar some 2,000 miles from Cocos. We started with good conditions, broad reaching in southeast winds from the upper teens to high twenties. It would have been pretty perfect, except for big seas on the beam for which the Indian Ocean is notorious. These are generated by powerful weather systems in the Southern Ocean and typically conflict with wind-driven waves generated by strong trades. Nonetheless, we made good progress in our “washing machine” although it was wet and bumpy. We were getting a little cocky, thinking that maybe the Indian Ocean wasn’t so bad after all. But then, still 600 miles out, we noticed that the GRIBs were beginning to show some pretty strong winds and we decided to get an updated forecast from Commanders’ Weather. We had obtained one before leaving Cocos.

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot! As it turned out the forecast was spot on, although we thought the seas topped out at 25 feet. As is often the case, the anticipation was much worse than the reality. We took advantage of a calm, windless day before the start of the gale to triple-check everything which could possibly move was secured. Commanders’ had told us that the seas would come in “distinctly different wave trains” and, given the size of the waves, we wanted to be ready in case of a knockdown. We made food, prepared our drogue to be deployed if necessary and got some rest.

When the weather hit we were down to triple-reefed main and partly rolled-up staysail. Kite handled the conditions beautifully and we were impressed by how well our Monitor windvane steered the boat. Conditions were quite rough, with huge, steep cresting seas which came at us from different directions. Winds were gusty and we encountered a number of squalls, some of which reached up to 50 knots. During the first night, we switched to two-hour watches from our usual three, but found we weren’t getting enough rest so went back to three on /three off. Although the wind and seas were roaring all around us, we would crash and sleep well on our off-watches. Our cockpit enclosure as well as our dodger took a beating. One dodger panel was ripped out by a wave, but Jack was able to sew it back up.

After two and a half days of strong gale conditions, we arrived in Rodrigues, 12 days after leaving Cocos. Needless to say, all three boats were happy to make landfall on this pretty island with rolling fields, steep hills and a very rural feeling. The population is mostly Creole and African and the place has a very laid back, sleepy vibe. After drying out, we spent a little over a week hiking, exploring and just hanging out. Sumptuous restaurant meals with drinks and wine were surprisingly cheap at about $20 per person. We and 10 other cruising boats were either anchored in the postage-stamp sized harbor (as we were) or tied to the wharf, which is also used by the weekly supply ship. Just about everything is brought from Mauritius on this ship. The little harbor was carved out of the reef and when the ship comes in, all the yachts are asked to leave for an hour or so while the vessel docks, using the anchorage as a turning basin.

We had a pleasant 350-mile passage to Mauritius in two days of light winds, calm seas and clear skies. In the capital city of Port Louis, we found a space at the crowded Caudan Waterfront Marina right in the middle of downtown where boats sometimes raft up three deep. We got lucky with our own spot on the outside wall. Mauritius, with a population of one point three million, is a stew of Creole, Chinese, Indian and European people which reflects its past as a plantation economy under the French and the English. Mauritius was also the only home of the ill-fated, flightless dodo bird (as Rodrigues was to its cousin, the solitaire).

We had ordered an Ampair water generator to replace the one we lost. A cruiser friend gave us the name of a Mauritian relative to whom we could have the unit shipped. Fortuitously, this led to our getting to know Jules, his wife, Dominique, and their two wonderful daughters. Their hospitality and generosity were overwhelming, and we got to sample some delicious home-cooked Creole cuisine. We had the World ARC fleet hot on our heels. All the cruising yachts in the Caudan Marina were told they had to leave so the ARC boats could stay at the marina. We had encountered the previous World ARC two years earlier in Fiji when they blew through Savusavu, but nobody was asked to move. Needless to say, they weren’t endeared to the cruising community.

But we were ready to leave and also wanted to get to Réunion before the ARC. An overnight sail took us to the marina at Le Port on Réunion’s west coast. The only other marina in St. Pierre on the southwest coast has only a handful of transient slips. There are no viable anchorages. As a result, Le Port can get crowded and most boats end up rafted two or three deep to a sea wall. We were again lucky to score a slip that belonged to a local boat hauled out for bottom work.

Réunion, volcanic and relatively young geologically, is spectacular, with a dramatic landscape of towering peaks and massive crater valleys. It also has a live volcano. Outdoor sports are big here and people come from all over the world to hike the well maintained trails.

The exercise made us feel less guilty about all the good meals we ate. Réunion is French, which meant excellent restaurants and markets filled with tasty things. We admit to a slight culinary prejudice towards the French or formerly French islands, whether in the Caribbean or the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

We organized several multi-day hikes where we stayed in gîtes, simple accommodations in shared dorms which also serve hearty dinners. Climbing the active volcano, with its vast lava fields, was one highlight, but the best was the 10,000-foot tall Piton des Neiges, the highest mountain in the Indian Ocean. We made it a two-day hike with Jake from Hokule’a, spending the night at the gîte de la Caverne Dufour at 8,100 feet. The next morning we got up at 3:00 a.m. to be at the summit for sunrise. Pretty spectacular!

But here too, the ARC was breathing down our necks. Incredibly, the marina Port Captains were instructed to clear all the boats from the crowded sea wall to make room for the ARC boats. This included local boats, some of which are live-aboards who were furious. With no anchorages in Réunion, this was potentially a real problem, though there is some limited space on an isolated wall, without water or electricity, that could accommodate a few boats. As we all looked for a weather window in advance of the ARC arrival “deadline”, we wondered if the ARC boats were aware of any of this.

We did get a window of sorts and embarked on the 1,500- mile passage to Richards Bay, South Africa. Four other yachts left Le Port the same morning including friends, Chris and Fiona Jones, on Three Ships, a Gitana 43. Hokule’a and Shango also departed the St. Pierre marina in the south, so we had quite a little fleet out there. The Indian Ocean again lived up to its reputation, throwing a variety of conditions at us. This passage proved to be our most challenging so far. We had three days of gale force winds, three days of no wind or wind on the nose when we had to motor, numerous squalls (including one that caught us by surprise with winds over 50 knots and zero visibility), and a frightening 6-hour stretch when we were in a huge and intense lightning storm with gusty winds, torrential rain and an adverse current in which we could only make one to two knots. Miraculously, we weren’t struck by the lightning. We had up to three knots of current with us sometimes and against us other times, all very unpredictable. On our second day out, our whisker pole broke when the screws on the fitting attaching it to the mast sheared off. We were pooped by a wave which sent a waterfall into the cockpit and down below. The hatchboards were (of course!) not in at the time and our bunk, with Zdenka in it, got soaked.

We stayed in daily SSB contact with Hokule’a, Shango and Three Ships and also participated in other nets during the course of each day. The last hundred miles are particularly tricky because we needed to cross the strong, south-flowing Agulhas Current. Low pressure systems were streaming off the coast of Africa every two or three days, bringing with them southwesterly winds which can create very dangerous wind-against-current conditions. Waves as high as 60 or 70 feet have been reported—something we never hope to see. We were shepherded in by the South African Maritime Mobile ham radio net, manned by volunteer, Sam Maree. Every morning Zdenka, our resident ham, would check in with Sam and he would give us a two-day forecast. As we approached the coast, he told us that our window to reach Richards Bay would close at 2200 hours the following day. We figured we could make it as long as we averaged six point two knots. We went for it, but then inexplicably we picked up a two to three knot adverse current which slowed us to less than five knots over ground and stayed with us all night. Like watching a pot boil, we kept checking the GPS which stubbornly had us creeping along. Finally with the dawn, the current changed in our favor and the wind picked up to the low 30s from the north. We were now charging along at nine to 10 knots, the sun was out and we surfed into the Richards Bay entry channel on a large northeasterly swell, a good seven hours before our window closed and nine days after leaving Réunion.

We were in Africa!

Zdenka and Jack Griswold sail Kite, their Bob Perry designed Valiant 42 cutter. You can follow their track by clicking on “Kite” at www.keelscape.com.