BWS takes a look back at some of the famous, notable and most influential small boat cruies of all time…and many are Americans (published July 2014)

You could say that the modern age of shorthanded and solo offshore sailing and circumnavigations came of age in the early 1960s with the first running of the Observer Singlehanded Transatlantic Race (OSTAR) from England to Newport, RI, an event that was won by Sir Francis Chichester.

Yet it was Blondie Hasler, one of the event’s founders, who made real waves by competing in a 26-foot folkboat named Jester, on which he had installed a simple to handle junk rig and he carried his ingenious invention, the Hasler windvane self steering gear. That simple invention changed the way we modern sailors go to sea.

Eight years after the first OSTAR, the Sunday Times newspaper in the U.K. launched the Golden Globe Race, which was the first singlehanded non-stop around the world race. It was sailed by the four great capes: Cape of Good Hope, Cape Leeuwin, South Cape and Cape Horn—all made famous by the clipper ships of yore.

Almost all of the boats that completed the event carried self-steering devices on their sterns. And some carried rudimentary mechanical autopilots and early roller furling headsail devices. Technology was evolving to make life offshore easier, safer and better for solo and shorthanded crews.

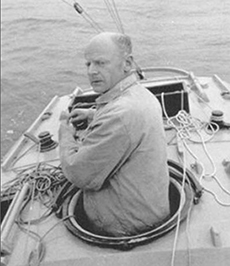

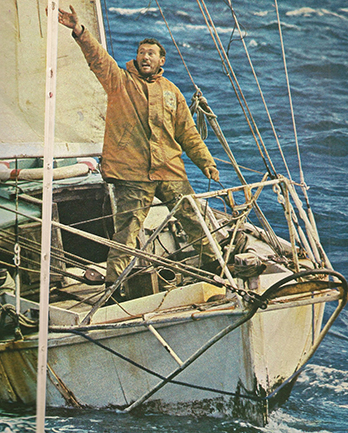

This first round the world race was joined by a fleet of most unusual gentlemen and created legends that survive today. It was the race in which we first met Sir Robin Knox-Johnson who won the event in the smallest and slowest boat, his 32-foot Suhali, but managed to finish in the shortest elapsed time. Knox-Johnson’s sailing career has spanned the decades and he has held records and trophies in all offshore genres. Today, Knox-Johnson is the founder and Executive Chairman of the Clipper Round the World Race that visited New York in June 2014.

Among the sailors in the first Golden Globe was Bernard Moitessier who abandoned the race at Cape Horn to sail on to Tahiti to “save his soul.” There were British paratroopers Bill King and Chay Blyth, neither of whom finished; but Blyth would go on to become one of Britain’s most illustrious offshore sailors. There was Nigel Tetley in a trimaran whose boat broke up not far from the finish line; poor Tetley was later found hanged in his closet dressed in women’s clothes.

And, the most infamous member of this gallery was Donald Crowhurst who set off late in the race in an ill prepared trimaran and preceded to file counterfeit position reports by radio as he secretly drifted around the South Atlantic. Crowhurst’s fraudulent track around the world was going to be the fastest and he was determined to finish first. But his mind gave out, he could not complete the fraud and his tri, Teignmouth Electron, was found adrift with her skipper missing.

Knox-Johnson became an international hero. Crowhurst became the anti-hero of a cautionary tale of ambition gone wrong at sea. And the Golden Globe became a model for the shorthand offshore races that would follow. These events have become the proving grounds for yacht design and yacht equipment that would shape small boat voyaging in the modern age. And from that era, the picture of little Jester sailing into Newport harbor with Blondie Hasler peering around from his hatch while his easy to handle junk rig drove her forward and servo-pendulum windvane gear ably steered the boat, is the first real picture of the modern age of small boat voyaging.

EARLY SMALL BOAT VOYAGES

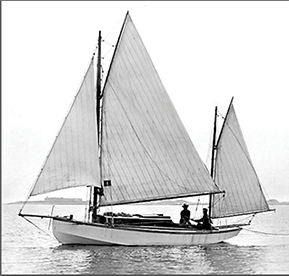

But men had been going to sea in small boats long before Hasler, Chichester and Knox-Johnson. It is interesting that Americans led the way in the world of small boat voyaging. For most of us, Joshua Slocum’s solo circumnavigation in the 1890s, made famous in his book Sailing Alone Around the World, marks the start of the age of voyaging under sail in small boats. Certainly, Slocum’s cruise west about from New Bedford, Massachusetts via Cape Horn, the Torres Straits and the Cape of Good Hope, which totaled 46,000 miles, was a magnificent feat of seamanship and small boat navigation. At 36 feet, Spray was no bigger than many ship’s lifeboats or gigs and was considered very small for such a voyage at the time.

Slocum’s book became a best seller and his lectures across America were given to huge, amazed crowds. One man was inspired by Slocum to try his hand at small boat voyaging. John Voss of Victoria, B.C., Canada, who was an experienced sailor, fitted out a 30-foot Native American war canoe and sailed it singledhanded from Victoria to London, England via the Torres Straits and the Cape of Good Hope. Like Slocum, Voss earned his way by giving lectures and eventually wrote the excellent book The Venturesome Voyages of Captain Voss.

Slocum inspired many Americans to follow in his wake and Voss did the same for many Europeans and, surprisingly, the Japanese. In America, the founder of The Rudder magazine (1890), Thomas Fleming Day, was already a force in the offshore sailing community along the East Coast and through his magazine did much to promote the Slocum and Voss voyages. To prove his critics wrong about the dangers of sea voyages in small boats, in 1906 Day founded the New York to Bermuda Race, which he won. The race has been run ever since, and in 2014 the 49th Race to the Onion Patch departed in June.

Day was also a yacht designer and to prove that small boats could be sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, he designed and built the 25-foot yawl Sea Bird in which he and two friends sailed from New York to England. The feat opened the door for hundreds of Americans to discover the cruising and voyaging life in small, inexpensive boats and may have been instrumental in building a new enthusiasm for recreational sailing across America.

One such enthusiast was Harry Pidgeon, an adventurer and noted photographer. In 1917 he discovered in The Rudder Day’s plans for a 38-foot version of Sea Bird. Pidgeon copied the plans and built Islander, which he rigged as a yawl. In 1921, he set off from California to become the second person to sail alone around the world and the first to do so via the Panama Canal. His voyage took four years and was made famous through The Rudder and in Pidgeon’s book Around the World Single-Handed.

In 1932, Pidgeon embarked on a second solo circumnavigation aboard Islander that lasted five years. Prior to building Islander, he had never been to sea and was in no way a sailor. Yet, he thrived on the life and was able to collect thousands of photographs that form a valuable ethnographic record of remote regions and native populations of the world at that time. His photos are in the Cabrillo Museum in Los Angeles.

While Americans might have pioneered the realms of small boat voyaging, today the French, and Europeans in general, dominate the shorthanded and small boat racing and cruising fleets. In France, sailing is on par with baseball in America and skippers are known in the general public by their first names. So it is worth noting the first Frenchman who had a burning desire to sail the oceans in a small cruising boat and discover the world on his own terms.

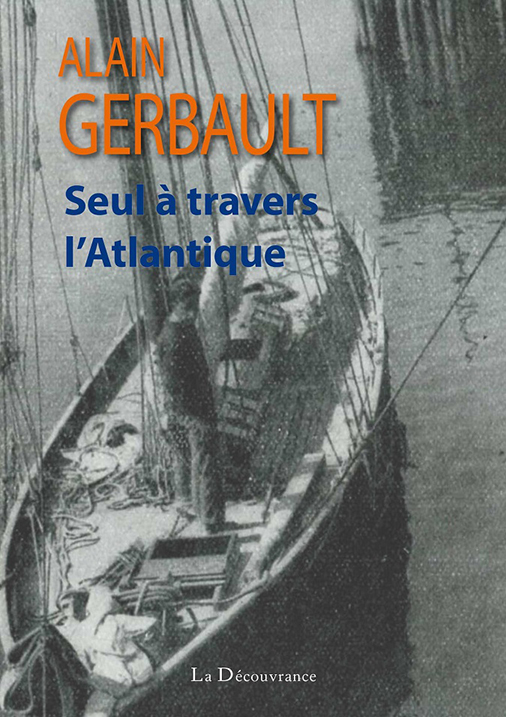

In the 1890s, Alain Gerbault was born to a well to do family in Brittany where he learned to sail on his father’s yacht and learned the ways of the sea from the local fishermen. He was a smart, shy boy who was gifted with languages and was an expert lawn tennis player. After World War I, in which he flew fighter planes, his dream of seafaring led him to buy the British- built sloop and in 1923 he departed France for a solo voyage to America. The transatlantic passage was a disaster and he nearly lost both his life and . Plus, he found the need to steer the boat exhausting to the point of collapse. Yet, he prevailed and was greeted in New York as an adventurous hero. As it happened, he arrived in New York in time to play in the U.S. Tennis Open. He didn’t win.

Gerbault’s voyage around the world, as chronicled in his book Flight of the Firecrest was one long adventure and misadventure from start to finish. Yet, it was also an inspiration for others who followed since Gerbault strove, met adversity and ultimately prevailed. Following his circumnavigation, he no longer felt fit to live in modern European society so he built a smaller, more modern cruising boat and sailed back to French Polynesia. Like Gauguin, he wanted to go native and be left alone in paradise. If you ever wonder what motivated Moitessier to “sail away to save my soul” you only have to look back to Gerbault.

Gerbault’s voyage around the world, as chronicled in his book Flight of the Firecrest was one long adventure and misadventure from start to finish. Yet, it was also an inspiration for others who followed since Gerbault strove, met adversity and ultimately prevailed. Following his circumnavigation, he no longer felt fit to live in modern European society so he built a smaller, more modern cruising boat and sailed back to French Polynesia. Like Gauguin, he wanted to go native and be left alone in paradise. If you ever wonder what motivated Moitessier to “sail away to save my soul” you only have to look back to Gerbault.

There were may other less heralded but still intrepid shorthanded small boat voyages from the decades before World War II, such as American Edward Miles, who sailed his 34 foot sturdy sloop on the first east about circumnavigation via Suez and Panama. Yet, it was only after World War II that the numbers of sailors ready, willing and able to set off on small boat voyages grew from a trickle to a flood.

MODERN SMALL BOAT VOYAGES

After the war, as Europe put itself back together and the rest of the western world become increasingly prosperous, people had more time and money to take up lifestyles like the cruising life. A sailing industry was beginning to form and fiberglass was making boats easier to build, stronger and more adaptable to modern design innovations that eluded builders of wood boats.

Yet, in the 1950s, wood boats were still the norm and one, in particular, Wanderer III, was destined to be a paradigm of the modern couple’s small cruising boat. She was a 30-foot Laurent Giles design, carvel planed on oak frames with a simple sloop rig with hanked on headsails and round-the-boom roller furling on the mainsail. She had a cruising full keel with a cutaway forefoot and an attached rudder.

She was owned by the British couple Susan and Eric Hiscock who were experienced coastal and offshore sailors, most notably cruising in and around the British Isles. Aboard their new Wanderer III, the Hiscocks set off from England in 1952 and headed west with the sun on a three-year circumnavigation via Panama, the Torres Straits and Cape of Good Hope. Their voyage was a model of prudent, modern voyaging along the trade wind routes. The Hiscocks were great planners, were careful in their preparation and always practiced prudent seamanship. The book that followed the circumnavigation, Wanderer III Around the World, is not only a fine cruising yarn, it is also by example a terrific primer on how to do it right.

The Hiscocks would go on to make two more circumnavigations and build two new Wanderers along the way. Yet, the small boat voyage in their 30-foot Wanderer III may have been the best of all.

Not only were the Hiscocks competent voyaging sailors, they were also good writers and eager to pass on the knowledge they learned over the miles. Hiscock’s books Cruising Under Sail and Voyaging Under Sail (now combined into one volume called Cruising Under Sail) are the early essential guides to buying, fitting out and preparing for blue water sailing. They are dated by today’s standards, yet they still contain kernels of wisdom that often are missing in today’s tomes. They are books that certainly launched thousands of cruising dreams.

In the 1950s, the English couple Myles and Beryl Smeeton had retired from mountain climbing and taken to the sea aboard a 43-foot ketch named Tzu Hang. They were an intrepid couple and made adventurous voyages all over the world. Myles later wrote several wonderful books about their adventures including the tale of pitchpoling off Cape Horn. Certainly, the Smeetons were early pathfinders for cruisers who would follow. On that voyage to Cape Horn, chronicled in Once is Enough, the Smeetons had with them a young Englishman named John Guzzwell who was both a fine young sailor and an accomplished boatwright. It was a good thing he was along. When Tzu Hang pitchpoled, she lost her rig and had the wood hatches torn from the deck. It was Guzzwell who put her back together again, carefully, expertly so she could sail back into Valparaiso, Chile 68 days later with all souls aboard safe.

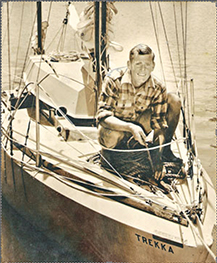

Guzzwell had met the crew of Tzu Hang in Hawaii where he was cruising aboard the 21-fot Laurent Giles sloop Trekka that he had built in British Columbia. The two boats cruised in company for several months and finally, in New Zealand John decided to store Trekka for a time so he could sail with Miles and Beryl around Cape Horn. The rest was history. Guzzwell left Tzu Hang in Chile and traveled back to New Zealand were he launched Trekka and carried on around the world. He returned to B.C. in 1959, having completed a singlehanded circumnavigation in the smallest boat on record.

During the fifties, dozens of sailors made small boat voyages that expanded the cruising horizons and helped evolve the design and rigging of modern cruisers. If the Hiscocks and Smeetons were the marquee cruisers of that decade then Robin Lee Graham was the name in lights in the sixties. In 1965, as a brash young teenager of 16, Graham singlehanded a 24-foot fiberglass Lapworth sloop, Dove, from California to Hawaii and along the way hatched a plan to become the youngest person to sail solo around the globe. Surprisingly, his parents went along with scheme. Even more surprisingly, National Geographic magazine agreed to carry installments from Graham along the way.

Graham departed Hawaii in September 1965 and cruised south and west to the islands of the South Pacific. He cruised and explored the islands and met the natives, and by the time he was 17, he had a year of blue water sailing and cruising under his keel and he was on his way west toward Australia and Southeast Asia. But he was still just a guy out there living the dream.

That all ended in October 1968 when the first installment of his cruise appeared in a full feature in National Geographic. In those days, the Geographic had one of the largest readerships of any magazine and it was truly worldwide. Something happened. Graham’s story struck a chord in the Baby Boom Generation like almost nothing else, whether the readers were sailors or not. Here was a young man who had stepped off the merry-go-round and headed off to see the world aboard his own sailboat. In the following two years, Graham published two more stories in the Geographic and in the process became a celebrity, something he had neither sought nor wanted. But there it was.

He returned to California in 1970 to a celebrity’s welcome. Ford gave him a brand new Mustang. Book publishers buried him in proposals and contracts. TV crews wanted sound bites. Graham tried to reintegrate himself into the world but couldn’t. He sold the Mustang, bought a hippy van and headed to the solitude of the Montana mountains where he and his wife Patti built a log home and raised their two children. But he had left his mark. Thousands upon thousands of young dreamers got the bug to go cruising and, not surprising for the Baby Boomers, many of them did. His book recounting the voyage, Dove, became an international best seller and continues to sell well to this day.

“Go Simple. Go small. Go now.” That is the mantra of all small boat voyagers today as it has been for nearly 40 years since it was first coined by Lin and Larry Pardey. Today, after two circumnavigations, more than 170,000 sea miles, 11 books, five DVDs and hundreds of magazine articles and lectures, the couple has become the face of cruising in America and around the world. Yet, when they started out in 1968 aboard the 24-foot Lyle Hess-designed Seraffyn, which Larry built with his own hands, they were just two free spirited adventurers with a passion for the sea.

For the next 11 years, they wound their way east about the world from California to Europe via Panama, then Europe to Asia via Suez and finally back to California in 1979. Along the way and after their return, they wrote the now classic cruising books Cruising in Seraffyn, Seraffyn’s European Adventure, Seraffyn’s Mediterranean Adventure and Seraffyn’s Oriental Adventure.

After all those years living cheek to jowl aboard their 24-footer, the Pardey’s needed a bigger boat. They had asked Lyle Hess to design it for them and in the early 1980s they moved ashore into the hills of California so Larry could build Taleisin, their new 30-footer. The story of their years ashore is told in the highly regarded memoir Lin wrote called Bull Canyon.

Taleisin was launched in 1984 and soon the Pardeys were at sea again and on their way around the world, this time west about by the southern route via New Zealand, southern Australia, the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. This voyage lasted the better part of 16 years, with side cruises to the East Coast of the U.S., England, the West Coast and British Columbia. They cruised the world and went where the wind and their endless curiosity took them until they finally came to roost in New Zealand, which is now their home.

The Pardeys, who built their own boats, never sailed with an inboard engine, eschewed modern electronics, and stayed true to ancient traditions of the sea, and have always had their followers and detractors. Yet, they are quintessential cruisers and have inspired tens of thousands of sailors to go simple, go small and go now.

In the annals of small boat voyaging, Tania Aebi’s cruise around the world from May 1985 to November 1987 ranks as one of the gutsiest. At the ripe old age of 18, she set off from her home in New York City aboard the 26-foot sloop Varuna bound for Bermuda and then the Panama Canal. An indifferent student with a wanderlust, she had persuaded her father to fund her voyage instead of paying for college on the condition that she complete a circumnavigation and then write a book about it. But first she had to learn to sail and navigate.

Her first passage to Bermuda should have taken six days. Without a long range HF radio she could not report her position as she sailed southeast nor could she ask for help with her celestial calculations. After eight days, friends and family began to worry and after 10 there was real concern until she finally called in from a phone booth in St. George’s, Bermuda to report a safe landfall. As it turned out, she had missed the island on her first pass by 80 miles and only realized her mistake when she was well out into the Atlantic. Using a handheld RDF she located Bermuda Radio and was able to home in on its signal until she was home and dry.

The voyage and Tania’s skills improved with each landfall as she sailed to Panama and then on across the South Pacific by the trade wind route. Gregarious and full of fun, she made friends wherever she sailed and impressed other cruisers with her pluck and courage. Her mission was to become the youngest person and first American woman to sail solo around the world. No small task.

But life has a way of interrupting plans. In Vanuatu, Tania met a young French singlehander named Olivier and fell in love. From there onward, they sailed in tandem, Varuna and Oliver’s black ketch Akka, over the top of Australia, through Indonesia, across the Indian Ocean and up the Red Sea. They were inseparable but still sailing solo.

In Malta, Tania’s mission came into clear focus. If she dallied for the next winter she would lose her chance to break the records she had in her sights. If she left, she would be leaving Olivier behind because he was not planning to cross the Atlantic again. So she set off alone and lonely to make the passage to Gibraltar and then straight across the Atlantic to New York in the weather window between the hurricane season and the onset of winter gales.

She arrived in New York on November 6, 1987 and was greeted at New York’s South Street Seaport by a huge crowd and the international press. She had done it. And even better, Olivier surprised her by being there to welcome her home. Her book, Maiden Voyage, written with Cruising World magazine’s then Deputy Editor Bernadette Brennan (now Bernon), became a best seller and Tania’s tale, like Robin Lee Graham’s, has become an inspiration for young sailors around the world.

While not as famous as some of the small boat voyagers who have sailed solo around the world, Donna Lang is one sailor whose tale is also an inspiration for women and all sailors who want to just go out there and do it. After a personal tragedy disrupted her life, Donna, who is a professional musician, went to sea as a cook on a tall ship. She fell in love with the sea and forged in her mind the idea that a solo trip around the world, with only one stop, would be the only thing that would lead her back to the personal peace that she had lost.

With almost no money, she managed to buy a Southern Cross 28, Inspired Insanity, and fit it out with the essential gear needed for safe passagemaking. She made a solo trip from Bristol, RI to the Virgin Islands and with that trial voyage under her belt set off for the 168-day voyage around the Cape of Good Hope to New Zealand. Along the way she met every type of weather from calms to repeated southern ocean gales. Her little boat was often overwhelmed by huge seas and had to lie to a sea anchor. Yet, she made it and was welcomed in New Zealand warmly. She spent months in New Zealand refitting her boat and then set off for the nonstop passage around Cape Horn and on to Rhode Island. Off the Horn she was near a yacht that was dismasted and needed assistance. While other cruisers came to the rescue, Donna managed communications via her sat phone and was able to facilitate the rescue of the other boat and crew. Although she had not planned to stop, she diverted to Puerto Williams in Chile to finalize the rescue and meet her new friends.

From Chile, she sailed north and was just days from Rhode Island when she met a huge spring gale that forced her first to heave to and then ultimately to retreat to Bermuda. She had closed the circle for the circumnavigation and in the process, had inspired many ashore while finding in herself the new sense of well being and peace that tragedy swept away.

The final small boat voyage that needs to be part of this compendium belongs to Matt Rutherford of Annapolis, Maryland. Like most voyagers, Matt had a mission and set out to fulfill it by sailing alone around the Americas via the Northwest Passage and a rounding of Cape Horn.

Already an experienced solo sailor with an Atlantic circle under his belt, Matt conceived of the voyage around the Americas as a way to test himself while raising money for CRAB (Chesapeake Region Accessible Boating), which provides access to sailing for the handicapped. Rutherford had had a very rough start in life and had been on a path toward prison as a teenager. He had fought his way free from that life with some help from others and had come to deeply understand how important giving back to society is to becoming a whole man.

Rutherford undertook the voyage between June 2011 and April 2012 and sailed in a borrowed Vega 27 named St. Brendan with a Monitor windvane on the stern. His solo trip through the Northwest Passage was not the first, but it was accomplished with steady competency and sound seamanship. The nearly pole to pole voyage down the length of the Pacific Ocean was no small feat in itself, yet he made it sound like a pleasant cruise in his regular blogs. Rounding the Horn was a huge milestone and the last real turning mark of the course. He made it without too much fuss or bother. Matt’s that kind of sailor.

But the boat and its system were suffering from the strain of the voyage so he was forced to heave to off Recife, Brazil so friends could restock him with supplies and gear. Ten months after departing the Chesapeake Bay, Matt sailed under the Bay Bridge and then on to Annapolis, Maryland. He had raised more then $130,000 in donations for CRAB and had sailed himself into the form of a full-fledged man.

EPILOGUE

Small boat voyaging is not for everyone nor is solo or shorthanded sailing. Yet, it is always a pleasant surprise for those of us who cruise in larger boats—most cruisers, especially couples, are sailing 40-footers or larger these days—to sail into a far flung anchorage and find three or more small boats under 30 feet that have crossed oceans and arrived safely and almost always on a very limited budget. What the famous small boat sailors teach us over and over is that it is not necessarily about the size of the boat, it is about the size of the dream.