Your best bet for nav data transfer (published November 2012)

There are many reasons these days to transfer navigation data among GPS and e-chart devices. Here are just a few.

1. The easiest way to lay out a route is to select and then fine tune the waypoints on an e-chart program on your computer rather than enter them directly into the onboard GPS. These programs (including many free or open source versions) have better graphics and view options than any dedicated onboard system, not to mention that many show tides and currents as a function of time to help plan the route. Then, when your final list of waypoints is made and checked, you can transfer the list to your onboard navigation system using methods we discuss here.

If I might insert here an easily defendable bias, the electronic route layout is usually best done with a “real e-chart,” i.e. actual graphic image of the printed chart (called RNC, for raster navigation chart) rather than on a vector chart (called ENC, for electronic navigation chart). This is one more reason to lay the route out on a computer and then transfer it to the onboard system, because the internal charts of dedicated GPS systems are all vector-based. In the next column, I will discuss the pros and cons of ENC vs. RNC.

2. Once you have a set of waypoints in your onboard system, it is always valuable to back up the waypoints by installing the same route on at least one handheld GPS. Racing or cruising, it could be crucial to be ready to go with the next waypoint and present tracking in case the main system fails. Also, with the data in a handheld, you can have several folks watching the navigation from the deck, and not rely on just the ship’s display screens.

3. After a cruise or race is over, you may want to document where you were and save it as a record for future use, or go back and see what you might have done right or wrong in a race. This calls for getting the saved track out of the onboard GPS and into your computer.

4. You may want to share your voyage with a friend or the public by posting your route on the Internet. Google Earth (GE) makes it very easy to post a track or set of waypoints online that can be viewed privately by selected contacts or published to the public. The GE display of your route on a satellite image gives a wonderful perspective of your travels. Needless to say, all we discuss here applies to a bike trip or hike as well as a voyage.

5. In a pinch, you could also use GE to lay out your route and then export that in a format that can be imported to your onboard GPS. This might be an advantage for a small boat trip, going in and out of places that are not charted to the detail you want, but for a larger boat trip, it is generally best to do the layout on the RNC version of a nautical chart showing all navigation aids, because we want to coordinate our waypoints with nav aids when possible. In some remote parts of the world, however, the GE images might be notably more detailed than available charts, so it remains something to keep in mind for all vessels.

6. Then there are more nuanced reasons for waypoint transfer. For example, in areas affected by strong tidal current flow it is crucial to know where the closest current station is located. Some electronic charting systems (ECS) include the tidal stations, so you can just press a button to show where the stations are and what the current is at the moment. Other excellent programs do not have this feature, so we need to enter the stations by hand. This can be very tedious for an extended trip, so obtaining a digital list of the stations online and converting them to waypoints the GPS can read is helpful. With these waypoints showing along your route, you always know the closest current reference point.

The nuance is this: In Canadian border waters, most ECS will show current stations well into the Canadian waters, but these are only the U.S. stations. The Canadian data are copyrighted so they cannot be included in this list. So, again, we have value in looking up a list of these Canadian stations online and adding them to our onboard GPS, even when we have a display current option that says it includes Canadian currents. These waypoints will not give you the actual currents—you need the Tidal Currents book for that—but they show where the data are available.

There are other reasons for data transfer, but enough background.

HOW-TO

The simplest and most universal method of waypoint transfer is the use of GPX files (called GPS Exchange). GPX files are in XML format, similar to HTML used for web page scripting, which means they are easy to read in a text viewer once you know the conventions. Essentially all GPS units and ECS systems can import and export in this format. These files can also be opened and displayed in GE.

If you have your waypoints already in a GPS unit or a computer, that is all you need to know. Export in GPX, then import in GPX. There will be other options, but this one is most often the best.

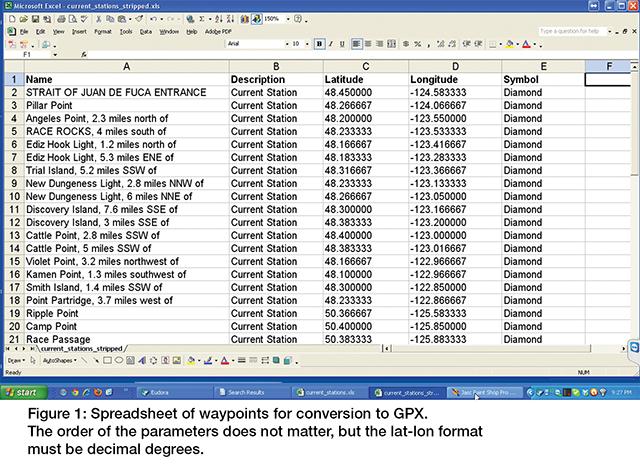

There is more to do if your waypoints are just a list of latitudes and longitudes. In this case we need to get more involved with the GPX format, because we need to create a name, symbol and description for each waypoint. You can read about the options for labeling waypoints at www.topografix.com/GPX/1/1/#type_wptType. The use of a spreadsheet like Excel is helpful at this stage. The lat-lon must be in dd.dddd format (N lat and E lon are +; S and W are -).

Next, we must account for the fact that the ECS programs are not standardized in the waypoint description option. In your GPS program, look at a list of waypoints. All will have a lat-lon, a name, a symbol, and either a comment or a description, but not both. So you have the option of using the one that is right for your program, or adding both parameters to the list you will import. For “symbol,” choose something simple like circle, square or diamond. Most programs have multiple symbol options, but it is best to stay with the basics. You should end up with a spreadsheet or text file that looks like Figure 1.

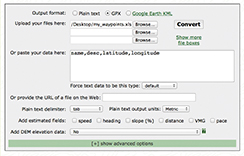

Next, we need to convert this list into GPX (XML) format. There are likely many options for this, but the one I have found most useful is a free online service at www.gpsvisualizer.com/convert_input. This server will accept spreadsheet or txt data, provided it is in consistent format (Figure 2). The online instructions are clear. Then just point the server to the waypoint file on your computer, and they will give you back a GPX file that you can use as discussed above. You can take a look at it in a text viewer to see the structure once you get it.

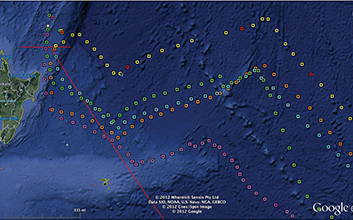

Figure 3 shows an example of the procedure. It is the GE track of the 5th leg of the 2008-09 Volvo Ocean Race showing the maneuver made by navigator Aksel Magdahl and skipper Magnus Olsson on board Ericsson 3 that won the race for them. With a bold weather analysis, they tacked northeast immediately after crossing the New Zealand scoring gate, leaving the fleet to take the conventional route to the south. After just two days they had gained a one-day lead, where they stayed to win the longest leg in Volvo history. A fine demonstration of weather tactics made by the unique team of youngest navigator and oldest skipper.

David Burch is the director of Starpath School of Navigation, which offers online courses in marine navigation and weather at www.starpath.com. He has written eight books on navigation and received the Institute of Navigation’s Superior Achievement Award for outstanding performance as a practicing navigator.