Part II: Life is but a dream on a passage from one unforgettable island chain to another (published November 2013)

On the eve of our departure from the Galapagos Islands to the Marquesas, each member of our crew was preoccupied with his or her own thoughts. Sure, we had already crossed the Atlantic, completed a round trip from the Caribbean up the east coast of the U.S., and sailed 900 miles beyond Panama into the Pacific. But the remoteness of this next stretch of ocean—all 3,000 miles of it—was something entirely different. I was thrilled to be standing on the starting line of a lifelong dream, but slightly overwhelmed by the scale of it all. Then there was the nagging concern about provisioning: had I stocked enough food, water and, most importantly, chocolate cookies to last the distance?

My husband, Markus, devoted most of his attention to tracking the immediate weather conditions around the Galapagos, an area of strong currents and fluky equatorial winds. Our eight year old son, Nicky, on the other hand, was too busy with ambitious Lego projects to think of pesky details like preparations aboard our 1981 Dufour 35, Namani. Bidding a fond adios to the cavorting sea lions, blue-footed boobies and marine iguanas of Darwin’s archipelago, we were off and away on April 2, 2012.

As things turned out, the passage could be divided into three distinct parts: an awful beginning, a long, glorious middle, and the home stretch. We couldn’t be choosy about a weather window once our 21-day Galapagos permit expired. The first three days underway were squally, with wind from the southwest. On port tack Namani could only manage a heading slightly north of west. And on starboard tack she tracked an even less inspiring eastward course due to the strong current. Where was the favorable west-setting current we had read about? In one miserable 24-hour period, we tacked over 100 miles to make ten good. It was a squally trial of patience and faith in many ways. We were desperate to make progress away from these contrary currents and into the trade winds.

Luckily, our misery was short-lived. The wind abated over days four and five when we motored south-southwest. On day six we found steady 15 knot southeasterly trade winds at last, and the tune of our days made a drastic change for the better, something along the lines of “merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily, life is but a dream.” The sky was a swath of blue dotted with a few fair weather cumulus clouds. What a pleasure to lean back, let the Hydrovane do the steering and watch the log tick off the miles as Namani sailed in pursuit of the setting sun.

KEEPING GOOD COMPANY

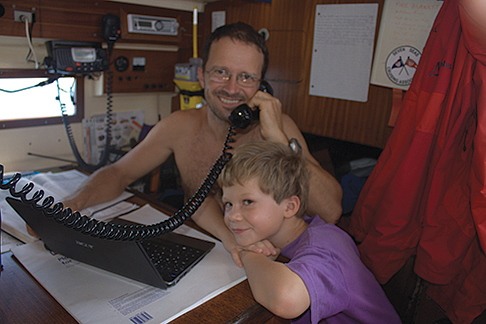

Back in the Galapagos, we had made many new acquaintances and set up two SSB radio nets: one English, and another German-speaking. In fact, these were just two of many, including the well-established Pacific Seafarer’s Net and a French-speaking net.

These provided twice-a-day social contact and just enough structure to pleasantly punctuate days on the open sea. As it turned out, an entertaining cast of characters populated the nets and listening was a little like tuning in to radio entertainment in the era before television. That’s one reason why Namani followed the ticks of two different clocks: UTC, for our constant appointment with the radio net crews, spread over many degrees of longitude, and our ship’s clock, which we adjusted periodically as our sloop sailed west.

Otherwise, we were on our own. In fact, we had more contact with animals than humans, given occasional dolphin, whale and seabird visits. Only once did we spot a fishing fleet, not far west of the Galapagos. Interestingly, other crews reported regular sightings of fishing boats throughout their passages, so perhaps this was just luck. It certainly wasn’t for lack of a good lookout. Markus and I spent our watches in the cockpit, ducking below only briefly to write in the log or dig out a snack. This can be a trial, as it was during those wet early days hard on the wind, or it can be a glorious feeling, as in the middle section of the trip.

OF SAILS AND STARS

After a shaky start, we were treated to the loveliest passage imaginable. Fair weather and steady progress were the order of the day, everyday. And we hardly had to trim the sheets! Weather systems that normally keep sailors on their toes seemed to be slumbering somewhere far away. In our little bubble around 8 degrees south latitude, every day was pleasant, and we slept soundly in the knowledge that tomorrow would bring more of the same. Namani’s slight rolling motion lulled us into a state of supreme contentment, like daydreaming babes in the cradle of the ocean. Where else but a boat can you be perfectly content to literally watch a day go by? A week? We could relate to the French sailor Bernard Moitessier, who got so into the groove that he didn’t stop upon completing one circumnavigation. He simply sailed on into the setting sun for another half circle of the globe—all in one non-stop journey poetically chronicled in his book, The Long Way.

By day, we flew the Parasailor, our light-wind miracle machine. Shaped like a spinnaker with a vented slot and wing for lift, this wonder sail dampens the roll of downwind sailing and keeps boat speed up. What had originally been a long-winded operation to set the sail quickly became a smooth, fifteen-minute process, with Markus hoisting the sock on the bow and me tending sheets in the cockpit. Once up, the Parasailor required next to no tending, and the Hydrovane kept things steady with small rudder movements. We were free to sit back and enjoy the “eco-friendly” ride.

At night, we would swap back to the genoa. For this trip, we replaced one of our old headsails with a special twin sail—two flaps sewn on one luff tape—that flies like a twistle, without the extra set up. Downwind, the flaps open up like a small spinnaker—one that can be furled to any size with an easy adjustment from the cockpit, even while one flap remains poled out. As a cautious crew who values undisturbed sleep for the off-watch person, we prefer trading comfort for speed and therefore douse the Parasailor even on apparently quiet nights. It’s a strategy that pays off. Another crew reported midnight shenanigans when trying to douse their spinnaker in one of the few squalls to cross our general cruising track.

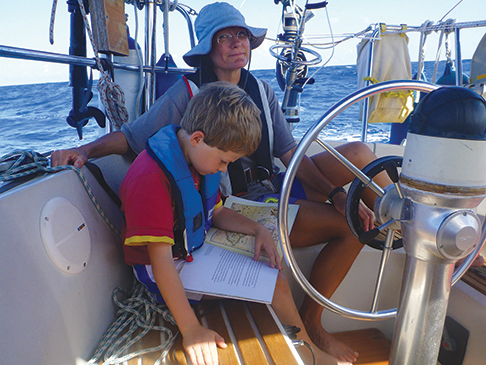

Keeping a steady schedule of four-hour watches, day and night, was another aspect of the pleasant rhythm that we fell into. Markus took the early watch, from 06:00 to 10:00, serving as one of two controllers for the English-speaking radio net during this time. I took over from 10:00 to 14:00, a time partly devoted to home schooling, plus baking bread and other goodies every third day.

Night watches had a quality of their own with both the Big Dipper and the Southern Cross in view. Standing port and starboard, they were like buoys leading us along a marked channel to land, far to the west. Clear nights also meant that Markus could aim our sextant at the sky just about any time he wanted for a star sight. Other than scanning the horizon, reading and plotting the time for my next snack, I passed thirty minutes of my 02:00 to 06:00 watch with an easy session of step aerobics. After all, 35 feet of fiberglass doesn’t provide much room for blood-pumping exercise.

And what exactly does an eight-year-old do for 28 days at sea? Doesn’t he feel bored? Cooped up? Lonely? None of the above—with a greater part of the morning devoted to school, plus a shorter afternoon session in his second language, German, Nicky happily kept himself occupied in his remaining free time. To begin with, there were Lego boats to build, which turned into massive marvels of engineering complete with working winches, cloth sails and swing keels. There were the adventures of Percy Jackson—the schoolboy demigod son of Poseidon—to read, and decks to patrol for flying fish.

Nicky also spent part of the early night watch in the cockpit, clipped in beside me, watching the stars. How many eight-year-olds are treated to down time like this, contemplating the grandeur of the universe with their parents?

Our weeks at sea were punctuated by special occasions, too. After a flurry of cake baking and craft making, Nicky and I helped Markus celebrate his 46th birthday at 08°S 110°W. We hadn’t brought gifts from “civilization” for this special day. Instead, we applied our hands, hearts and a little creativity to the materials available on board. The result was commemorative artwork; a bar of soap carved into the shape of a turtle, and personalized new lyrics to a favorite song, which made it a birthday to remember in both location and spirit.

Most exciting of all was our mid-ocean rendezvous with a French sailboat called E Capoe, which translates to something like “What the heck!” Position reports on the radio net showed that we were very close to this family of five. We had chatted on SSB, but never crossed paths until now. E Capoe’s crew is made up of a French father, Austrian mother and three trilingual kids—both their parents’ native tongues plus the Spanish they picked up while living in the Galapagos Islands where their parents worked as researchers. So it was with great anticipation that we compared positions and scanned the horizon.

Our first sighting came in the pre-dawn hours as just a dot of light ahead. Eventually, we raised a white sail and the mirage-like shape of a boat on the horizon. Like naval encounters of centuries past, the excitement stretched over half a day as the boats steadily drew closer. When Namani finally pulled alongside at noon, we all broke into silly grins and waved for all our arms were worth, compressing all our social energy into that one brief encounter. Then the mid-ocean photo-shoot of a lifetime commenced, producing countless images of each boat from all possible angles and various sail configurations. When we finally did get to spend time together in the Marquesas, we felt like old friends. The kids got along beautifully, and we were delighted to be able to cross paths on many later occasions—all the way from 118°W to 163°W longitude.

WHAT ABOUT THE BOAT?

Not every minute of an ocean passage is fun, but this particular passage had an embarrassingly high percentage of “good” and “great” moments. Smooth sailing and steady winds helped in that respect. There was little chafe or undue stress on the rigging, as regular checks reassured us. One day, my big job was to replace a slug on the largely unused mainsail. On day 26, Markus got a new perspective on our little universe when he climbed the mast to fix a weak connection in the tricolor light. Otherwise, the only “work” on the boat was topping up our water tank from a separate cache of reserves and refilling the diesel burned early in the trip with fuel from jerry cans.

All the boats we were in contact with complained of shaggy forests of gooseneck barnacles sprouting from their hulls. The radio net buzzed with solutions that ranged from the inventive to the insane. Someone suggested running a line under the hull to rub the barnacles off, a recipe that brought mixed results. From the “don’t try this at home” school of thought came the plan to go overboard for hand-to-hand combat. Bruce from Adventure Bound not only cleared the growth in this way, but also speared two mahi mahi while he was at it. This was not, however, an approach anyone else chose to try. We went with the “ignore” option and attacked the inch-long pests at anchor at the end of our journey.

THE HOME STRETCH

The nets also hosted discussions on the feasibility of making an illicit stopover in Fatu Hiva before officially clearing into French Polynesia on Hiva Oa, 45 miles farther downwind. It was a tempting prospect, indeed, to avoid a long windward run. The gorgeous Bay of Virgins on Fatu Hiva ranks as one of most beautiful anchorages of the South Pacific, and nobody wanted to pass it by. Radioing ahead to crews who had already made landfall brought a halt to all this speculation, however, after a report came through of regular patrols threatening hefty fines for illegal stopovers—whether or not these fines were ever collected was an unresolved question. In a way, this is a good thing, as the windward passage weeds out much of the fleet and leaves Fatu Hiva in relative peace, a true reward for those willing to tough it out for a day.

The wind only faltered on the last four days of our passage, a mere Force 3 that wafted us gently forward. The Parasailor helped eke out the last few miles, but boats behind us fell into a windless void; some inched in to port after a total of 35 days underway. A few even came non-stop from Panama, a trip of over fifty days. When the lush, craggy cliffs of Hiva Oa came into view we were thrilled, but also sad to end this lovely passage. One of the most peaceful, magical times our family has ever enjoyed was coming to a close. It was entirely unlike our Atlantic crossing a few years before, which had been a more erratic, trying passage with conditions ranging from dead calms to ugly squalls. Now, we arrived fresh and eager for more sailing. And a good thing, too, since inter-island passages within the Marquesas have more in common with open ocean sailing than coastal cruising.

By lunchtime on April 30, Namani was anchored in the tight quarters of Traitor’s Bay, with one anchor ahead and another astern to keep her oriented into the light swell along with twenty-odd other boats. One of our radio net buddies kindly dinghied up with a welcome basket for us—huge, succulent pamplemousse, crisp green lettuce and, of course, a fresh baguette. With misty mountains all around, we immediately fell in love with the Marquesas. Namani had covered 3,300 miles in 28 days. The big one—the longest single passage of our three-year cruise—was behind us, and will forever remain a sailing highlight.

Nadine Slavinski is the author of the book Lesson Plans Ahoy: Hands-On Learning for Sailing Children and Home Schooling Sailors. Currently on sabbatical from teaching, she cruises aboard her 35-foot sloop, Namani, with her husband and young son. They are currently in New Zealand and looking forward to new Pacific landfalls. Her website, www.sailkidsed.net lists free resources for home schooling sailors.