All of the weather forecasts from multiple sources indicated a likely and potentially dangerous passage. The real question was whether or not we would have the courage to stay tied to the dock or would ego and momentum keep us moving towards departure (published October 2016)

I still have a bittersweet memory of the 2016 Newport to Bermuda Race. Aboard Moondance, a Swan 56, everyone on the crew had deeply searched their souls following a number of weather briefings and prior to our crew meeting before the start of the race. During the meeting we would need to individually and collectively decide on whether to start the race. What were our individual priorities? Our own capabilities? How had we prepared for heavy weather during the previous year? What were we willing to endure for the opportunity to race—again— to Bermuda? My mind turned back to similar decisions in very different circumstances years ago.

PAST EXPERIENCE

The Whitbread Round the World Race in 1985 aboard Drum was hard even long before the start. Six weeks prior to the start, the keel had fallen off the boat in the Fastnet Race, and the boat required a hasty major refit in order to get to the start line. Successful in getting to the start, the first leg of the race had provided a rough passage from England to Cape Town, South Africa. Drum had almost sunk —again! On that then-most-recent trip in 1985, several of the flat panel composite sections had failed in the forepeak as the core sheared due to the constant pounding into heavy seas. The mast step had collapsed, leaving the shrouds slack and threatening to bring down the rig. And one of the life rafts had started to auto-inflate, leaving us with too little room in the remaining raft to accommodate the entire crew. Safely in Cape Town and with a major refit completed only a day previously, we had one day for sea trials before beginning the next leg of the ‘round the world race—a passage through the Southern Ocean from Cape Town to Auckland, New Zealand. Racing across the huge seas of the Roaring 40’s and Screaming 50’s, would we live to see New Zealand? Would the boat hold together this time? How could we know after only a few miles of testing the boat in Table Bay? It was up to each of us to decide whether we would re-join the crew or remain safely behind.

What would you do? Think hard about it, because it’s the same thought process, if not the same exact details, that you undertake every time you untie the dock lines. And on Moondance in 2016, a superbly prepared stout and quick boat we would have to face wrenching decisions, as well. The circumstances were quite different, but the thought process needed to be the same as we all wrestled with our thoughts and the heavy weather forecasts for hard blowing and cascading, steep seas out of the east during the Gulf Stream crossing.

Whether you think about it as peer pressure or herd instinct, we all feel like we’re part of a larger team or group from time to time. There is a compelling instinct to move with the group or fleet, upholding our own position or place of responsibility within that group. It can be, and often has been, the glue that has kept groups of humanity together, alive and thriving, whether it was communities of farmers collectively raising a pole barn or prehistoric men hunting wooly mammoths. It’s a primal instinct, but it can also lead to disaster or even to one’s demise.

Several years ago, rally sailors heading to the Caribbean faced potentially dangerous weather prior to departure, as well. It happens. Sometimes, when already at sea there may be little we can do in order to avoid the heavy weather assuming the system is so large or so sudden that we can’t sail beyond the storm’s grasp. Prior to departure, however, we are faced with a different circumstance. Each of us is ultimately responsible for his or her own decisions, and that includes the decision to leave port or remain safely behind. Those decisions are based on multiple criteria: we enjoy sailing, the weather looks acceptable at the very least, and we want to spend the time enjoying the company of our friends at sea. Certainly other considerations are part of the mix as well, as we think about how well the boat and crew are prepared for the passage. Usually, we come to those conclusions correctly, and the day sail or long passage results in great times and memorable miles. Sometimes it doesn’t. And for a very few of those rally sailors, leaving with the promise of heavy weather ahead, it resulted in tragedy.

I’m not really qualified to speak to their own circumstances, although there are those who suggest that those unfortunate sailors left port in order to stay with the group. Perhaps. It is, after all, a strong instinct and one which can benefit or harm any one of us. It may be that the decision to leave was partially based on someone’s schedule, another notoriously bad reason to make potentially dangerous choices. Perhaps the best take away lesson from which we can all benefit is to review the decision making process. I can certainly attest to the fact that, while my decisions have not always been good, for the most part, they have all been informed, and most of the time, that information has been correct within understandable parameters.

DECISION MAKING

DECISION MAKING

In 1985, when we were confronted by similar decisions aboard Drum, with the Southern Ocean looming just over the horizon, we each had to come to our own conclusion. The easy way out was to merely say “Sure. I’ll go!” It was a non-decision to remain with the “herd”, or in that case, the same guys who had sailed together for the previous month, confronting serious, potentially deadly circumstances, and working together, lived to tell about it. We were a close-knit team, and compliance with group-think would have been easy. Ultimately, we knew however, that it was our individual responsibility to make our own decision. Hassa, a Swedish crewmember, made our own individual decisions possible when he made the most courageous decision of all. He decided to remain behind. It was then and still is in my mind now that his decision enabled the rest of us to come to our own independent conclusions.

I have had that thought often throughout the following decades. Hassa’s independent decision enabled us all to form our own course of action. How then do we form our own courses of action while working within the larger group without someone like Hassa leading the way in another direction? Within the context of sailing we often hear the opinions of others. Regarding whether or not to depart on a particular weather pattern, we may listen to the guy on the boat in the next slip, or we may get a weather forecast from a company like Commanders’ Weather, professionals at looking at weather and offering suggested routes to some very qualified clients.

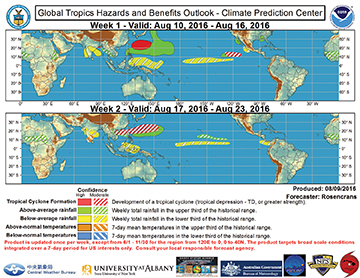

Whether I’m doing deliveries down to the Caribbean or racing across the North Atlantic, I always access the weather and routing advice from Commanders’ Weather. Prior to reading their forecasts, however, I look at weather maps, read text forecasts provided by the Weather Service and study satellite imagery. I’ve spent time learning the tools, and I employ those tools to determine my own view of the situation and route. I form my own opinion prior to subjecting myself to the opinion of others.

As I then delve into the weather forecast provided by Commanders’ Weather or the maps provided by the Ocean Prediction Center, I try to find areas in which we agree or disagree. I’m not particularly bothered by either case. I don’t assume ownership of my opinions or theirs. Rather, I’m looking for the range and limitation of agreement to get a better understanding of how stable the variables might be. If my opinion on the weather is in complete agreement with theirs, I have a relatively strong belief system that the weather forecast is solid. If our opinions on wind direction or speed might be at odds with each other, I try to better understand those differences. Is my projected position different from their understanding of where I might be located? Do they think a weather system will therefore pass north or south of me, while I think otherwise? Are my sources of information thinking that a weather system will be more or less severe than Commanders’ Weather? If so, I have a better understanding that the upcoming weather pattern may be a bit less predictable, and I may need to guard against the worst case scenario.

I’ve heard it said that if two people always agree on something, one of them isn’t necessary. Difference of opinion is a healthy state of affairs, leading both parties to reconsider the limitations of their own opinion. In the process a deeper understanding of the situation is achieved, and a better informed decision can result in a superior outcome. That is not to say that one opinion is always, or even usually, better than another. Rather it is to say that when there are differences, more research may be warranted, and the improved understanding will often lead to a better result.

Opinions of experts are just that: opinions. None of us has complete knowledge, although theirs may be more comprehensive in some areas. As an example, given a particular weather pattern, weather routers may suggest a particular route for us to take. But if they are unaware of the fact that we’re sailing on a multihull or West Coast sled, they may not fully understand that our ability to go to weather would not be the same as if we were sailing on a Swan 56. The meteorologists may understand the weather better, but they may or may not understand our ability or inclination to work within a particular weather situation. If we are sailing with a full crew of seasoned ‘round the world racers, we may be able to deal with heavy weather differently than a couple with three small children.

YOUR CHOICE AND YOURS ALONE

YOUR CHOICE AND YOURS ALONE

Ultimately, the choice to depart is yours and yours alone, and a well-informed, objective opinion can save your life. Aboard Drum, I’m still not sure if I merely took the coward’s way out, deciding to remain with the crew and finish the 1985-’86 Whitbread Round the World Race. In Cape Town we had watched every day as the re-fit was underway. We were informed. I am absolutely certain, however that Hassa made the courageous judgment call, avoiding the herd instinct and remaining behind. His courage enabled the rest of us to more freely determine our own course of action. As members of that “herd”, I hope that we all allow for and enable that kind of courage.

Following the collective decision aboard Moondance, we decided to withdraw from the race. I volunteered to help the race committee with any emergency call-ins as the fleet crossed the Gulf Stream. Happily enough, there were no major emergencies, and I spent the night chatting with friends in the Communications Center with whom I hadn’t connected in years. It’s a bittersweet memory, missing that race. But I have to admit that I’m proud of the way we came to the decision. That credit goes to the owner of the boat and everyone on board who individually faced their thoughts, studied the information at hand, freely voiced their thoughts and came to their own conclusions. mThose decisions are not always easy.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net