Part 1-Long the forbidden land just 90 miles from Florida, Cuba has a lot to offer cruisers (published July 2015)

“I think we are in a prohibited area,” my Finnish crew said casually, puzzling over his phone. He pointed toward the pink line on his Navionics app. We were already a mile inside by the time he awoke me. The cliffs that define the whale’s fluke of Cuba’s southern coast were sprinkled with busy wind turbines. Now two gunboats zoomed toward us across the Caribbean. Through the binoculars I saw that they belonged, not to the Cuban Navy, but the US Coast Guard. We had strayed into the military exclusion zone of Guantanamo Bay.

This was not an auspicious beginning to landfall.

The Coast Guard drew near, each vessel containing a half-dozen young men and a large, bow-mounted gun. I had heard reports of harassment by the Coast Guard in the Straits of Florida, and trouble was the last thing I wanted. After all, I could barely walk.

Since leaving the Bahamas three days earlier, my knee had swollen to the size of a pomelo. A fever had come and gone but I needed more medical help than my self-prescribed antibiotics offered, and soon. Cuba had only eight international ports of entry. Santiago de Cuba, her second-largest city and nearest entry point, lay 40 miles to the west; the others were all at least 350 miles away.

The Coast Guard vessels pulled up on either side of the boat, idling their substantial engines. What would they say about an American-flagged sailboat in Cuban waters? Would they demand to see the license I carried from the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control? Or were we in American waters? Could they arrest us for trespassing?

“Ma’am?” The seaman who addressed me looked the age of my son. “Ma’am, you have to keep three miles off for the next five miles.”

That was all. Not a word about the American-flagged vessel being in Cuba. It was as though they didn’t care. Relieved, I quickly apologized and turned the boat south. Our escort followed until we cleared the military zone before they headed back to base.

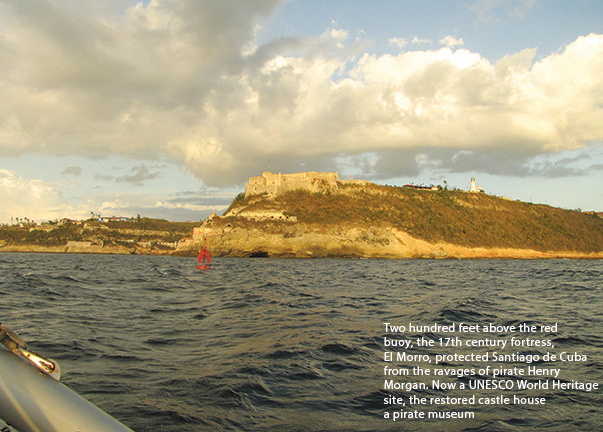

Late that day we reached the bottle-necked entrance to Bahia Santiago de Cuba. Nigel Calder’s Cuba: A Cruising Guide was nearly 20 years old, but the pilot’s waypoints did not fail us. Cliffs on either side left little room—at 0.2 nautical miles, the entrance didn’t look much wider than the Venezuelan oil tanker that had just passed through —but the water was deep with clear aids to navigation. High on the cliff behind the red buoy sat El Morro, the 17th Century castle-fortress that repelled repeated pirate attacks for more than a hundred years.

Though Calder’s waypoints were still good, a few other things had changed. We were not intercepted by the Guarda as we motored the mile between sea and safety (though it turned out they informed the port captain). The marina had been expanded since Calder’s visit, but now all that lay between us and a tenuous-looking quay was a man sprawled in an inner tube, fishing with a hand line. European-flagged boats were already rafted along one rough-looking pier. Closer in, a set of seven stairs rose to a platform and stopped midair; rebar protruded from what was left of the concrete pier like an autopsy gone wrong.

I dropped anchor several boat lengths away in five meters, hoisted the Q flag and waited for the port captain. He hailed and asked us to launch the dinghy to pick him up. Once he received boat documentation, and clearance, he explained in English that Hurricane Sandy had scored a direct hit on the marina in 2012. Hurricane or no, the cost of a berth with no running water and intermittent electricity was $.45 per foot per day. Like almost every entity in Cuba, the marina was state-owned—part of the Marlin group run by the Ministry of Tourism—and the state set prices.

I was happy to remain anchored out. For the next several hours, crew members ferried out a succession of officials to check us in.

A doctor was summoned to check the crew’s health. When the dignified, smiling man arrived he examined my knee, tsk-tsking in Spanish. After making a couple of phone calls, he informed me that I could see someone the following morning. I was not to go to the international clinic, where there was no orthopedic unit, but to the regular hospital. A team of professional, friendly customs officials arrived with spaniels to search the boat for drugs and inventory our electronics. An agricultural inspector checked fresh produce for insects; a veterinarian made sure we weren’t carrying meat. All the while, officials wrote answer after answer using carbon paper to make copies.

Well-educated and courteous, they explained each of the rules in English. Landing our dinghy on Cuban soil was prohibited except at marinas, but allowed in most anchorages on hundreds of largely uninhabited cayos. Dried or canned meat was okay, but fresh might be confiscated, depending on the country of purchase. We could keep our produce and eggs but not remove them from the boat except to dispose in special refuse bins. Americans must purchase health insurance at $3 for each day of their intended stay. Finally, immigration returned my passport with a 30-day tourist card tucked inside, a warning that it could only be renewed once and an admonition to change money as soon as possible. The captain owed $55 for the boat, $25 for each crew’s visa and $10 for the food inspection. Check-in would not be complete until it was paid.

The next morning the dock master, Cesár, arranged a taxi particular at $30/day for the 20-minute trip into the city. He also suggested I bandage my knee. Soon Omar, our driver, was waiting beside a red 1985 Russian Lada that turned out to be held together with a fair amount of duct tape. He shook his head at my gargantuan knee and suggested hot compresses.

Rolling hills offered a panorama of Santiago’s bay, studded with clusters of storage tanks and chimneys. Omar told us these were oil refineries and a cement factory. Passing fields cultivated in bananas, he joked about the better view of the sea opened up by the hurricane’s downed trees and pointed out scores of new tile roofs. He told us his wife, a nurse, was deployed to Venezuela as part of Cuba’s medical foreign aid program. Her service earned the right to buy a car. Owning a taxi left the mechanical engineer better off than the $20 average monthly salary in moneda nacional paid by the Cuban government. Though he kept only 10 percent of his take after paying for fuel, maintenance and taxes, the most lucrative —and indispensable— part of the job was tips in hard currency.

At the edge of the city Omar pulled in at a Casa de Cambio (CADECA). On entering, Omar addressed those waiting, “¿Quien es la última?” (“Who’s last?”) like someone used to waiting in lots of lines. When my turn came, I exchanged dollars at a rate of 0.87 CUC. Omar suggested changing 20 CUC into moneda nacional, the currency Cubans use for everyday expenses, at 24 pesos to the CUC.

In Santiago’s heart, the 16th Century Parque Céspedes, American classic 1950s cars were parked neatly near the hotel while drivers waiting for fares chatted with friends. A motor scooter leaned around the corner, neatly dodging a cart selling pieces of the huge papaya they call fruta bomba. Tourists asked about wifi (soon) as they watched men in fedoras and caps and cowboy hats set up a string-and-percussion quintet. No one was wearing fashionable or even new clothes. Cubans seemed poor, but healthy, and everyone seemed to be waiting for something to happen.

The next stop was ESEN, the government’s insurance agency, for health insurance. The receptionist looked at my knee and said I ought to see a doctor. The rest of the waiting room agreed.

As I thought about it, I hadn’t seen so much as a runny nose on the street. I observed that everyone seemed health-conscious.

“We hear it first from our grandparents, how to use ‘green’ medicine,” said the receptionist in Spanish.

“Then in school…” added a woman buying home insurance. “… and always on television announcements.”

Hoping to learn about the evolution of free health care in Cuba, I asked the receptionist whether her parents still talked about the revolution.

She rolled her eyes. “Ay, mi amor” —women seemed to call everyone mi amor —“they talk about nothing else.”

Once I had my insurance, Omar took me straight to the hospital. Like much of Santiago, the building was stark, peeling concrete. No frills at all, yet the facilities were clean, the staff was professional and Cubans exhibited good humor as they asked the inevitable, ¿Quien es la última?

After seeing a general practitioner, an orthopedist and an orthopedic specialist, my knee was relegated back to the duty GP, who diagnosed cellulitis. He prescribed an antibiotic and hot compresses until the infection came to a head and drained.

Omar ducked into a pharmacy with my prescription and returned with a two-week supply of ciprofloxacin. The cost was two pesos, about ten cents. Armed with drugs and a powerful curiosity, I began to explore the mysterious island known as the Pearl of the Antilles.

This is the first of a three-part, east to west exploration of the south side of Cuba. Christine (and her OFAC license) spent the season exploring Cuba, and blogging as Sissy Puedes in Cruising Compass. She and Stephan Regulinski cruised five years on Delos with their three children. Once they finish paying college tuition, they look forward to cruising again on Hanalei, another Amel SuperMaramu.