Sail repairs at sea are not a matter of “if” but “when”…since sails that are used hard offshore will eventually need your tender loving care (published April 2014)

As a team, we had crossed the North Atlantic twice and sailed from England to South Africa without a serious equipment failure. The sails had been pushed to their limits but never beyond. As we ventured into the cold Southern Ocean, however, that laudable record came to an abrupt end. Without warning, the sudden dull pop of the spinnaker exploding shook us to our feet and into action.

It happens. Usually, it’s unexpected. And watching sails disintegrate is never a joyful experience. Blowing out a sail is the result of any of a number of causes such as old tired thread, cold denser air providing a heightened force for a given wind speed, or just too much wind and pounding surf creating excessive loads. Most of those reasons can be avoided if we, as sailors, live within our means and accept the limits of our equipment. Of course, there are the unforeseen squalls, an out-of-sync wave or other causes for failure, but many of the reasons are avoidable.

Chafe is not your friend. Protect sails from chafing on lazy jacks, spreaders, sharp objects such as split pins or other sharp edges. Some hazards can be taped over and others can have a dab of silicon applied to soften the harsh or sharp edge. Lazy jacks can be especially destructive to laminated main sails on the leeward side. When the main is reefed, the resulting sail at the foot can chafe in unexpected places for longer periods of time, leading to premature aging. Even the most diligently applied preventative maintenance and careful procedures sometimes result in a torn sail or dramatic blowout.

If a sail blows out, get it down immediately and keep it onboard in the process to minimize additional damage. If the damage is to your mainsail, and you need it to continue moving, you may be able to reef above the damaged area. In any case, your first thought should be about damage control.

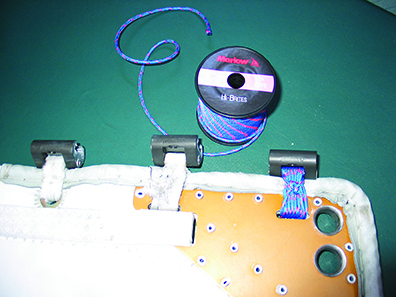

How you are able to repair your sail will be partially determined by the extensiveness of your sail repair kit. For extended passages, I fill a small duffle bag with items noted in the table on the following page.

How you are able to repair your sail will be partially determined by the extensiveness of your sail repair kit. For extended passages, I fill a small duffle bag with items noted in the table on the following page.

In addition to the noted items you might also include hardware such as spare slugs for the mainsail, spare hanks or climbers’ carabineers for use in a hank-on headsail or other types of hardware that you use in conjunction with your sail inventory, such as shackles for tack and head fittings or high tensile line to be used in lieu of bolt rope. Few boats carry such an extensive sail repair kit. Eventually, many wish they had. And, in fact, I’ve used every item mentioned above at one time or another and was happy to have the right repair equipment available.

As we were delivering a Gunboat 48 catamaran from Cape Town, South Africa to Norfolk, VA, we were sailing downwind in sunny, warm, stable conditions in the South Atlantic. Suddenly, and without warning, the spinnaker ripped an eight foot gash across the upper third of the sail. We scrambled to get the sail down before it got worse. However, in the process of taking the chute down, the tear worsened, and the lower part of the sail fell overboard between the two hulls. As we began to overrun the sail, the damage only worsened. Slowly, we brought the sodden heap back aboard. It appeared to be a devastating blow to our progress, given the fact this was our only true downwind sail, and we had more than 5,000 miles left of our passage. We got to work, using the sail repair kit described above.

Fortunately, the tear was along a seam. We didn’t lose any material, and it was a relatively straight rip. We took the sail into the saloon where we spread it out and began work on the seam. Starting at one end, we carefully cleaned the area around the failure, using fresh water to clear away the salt and using a little rubbing alcohol to help accelerate the drying process. We were able to match one side of the tear with the other. For the full length of the rip, we carefully applied a line of 4-inch-wide sticky-backed Dacron. We applied that strip in 12-inch lengths so we could keep the mend consistent and the edges of the original material in close relationship to the way they were originally aligned. After we applied a strip of the sticky-back sail tape, we used the handle of a screwdriver to rub it vigorously, firmly pressing the sticky-back to the torn sail and generating a little heat with the rapid rubbing friction. We went through that process on both sides of the sail, applying the sticky-back sail tape to both the inside and outside of the sail. Five hours later, to the amazement of the boat’s owner, we re-hoisted the sail.

Fortunately, the tear was along a seam. We didn’t lose any material, and it was a relatively straight rip. We took the sail into the saloon where we spread it out and began work on the seam. Starting at one end, we carefully cleaned the area around the failure, using fresh water to clear away the salt and using a little rubbing alcohol to help accelerate the drying process. We were able to match one side of the tear with the other. For the full length of the rip, we carefully applied a line of 4-inch-wide sticky-backed Dacron. We applied that strip in 12-inch lengths so we could keep the mend consistent and the edges of the original material in close relationship to the way they were originally aligned. After we applied a strip of the sticky-back sail tape, we used the handle of a screwdriver to rub it vigorously, firmly pressing the sticky-back to the torn sail and generating a little heat with the rapid rubbing friction. We went through that process on both sides of the sail, applying the sticky-back sail tape to both the inside and outside of the sail. Five hours later, to the amazement of the boat’s owner, we re-hoisted the sail.

The repair lasted for the remainder of the trip, at least 3,000 miles of which was sailed downwind with that sail pulling the cat.

Different sails, types and weights of sail cloth and types of failures require different types of repairs. You may be able to make the repair stronger than the original sail in that particular area, but that approach is of little value and may put stress on the adjacent parts of the sail. When making your repairs, take your time to do the job correctly. Doing a poor job may mean doing it again—if the next failure doesn’t result in complete destruction of the sail. Try to make sure that new seams are not puckered, and if you are stitching the sail together or tacking down the self-adhesive sticky-back material, realize that too many stitches and needle holes weaken the overall sail. When you resume sailing, understand that your sail is probably weakened so you need to reduce sail area accordingly.

On a few occasions, while racing in wild conditions with experienced sailmakers onboard, we have rebuilt sails after some of the material was completely destroyed or lost. Admittedly, the sail was a bit smaller than the original, but it still worked. You can put it back together again.

Sailrite is a great one-stop source for all of the tools you will need for making onboard sail repairs and they have really helpful instructional videos on their website that will help you grasp the techniques sailmakers and canvas experts use when making repairs. They also sell high quality sewing machines. Carrying a sewing machine aboard a cruising boat makes a lot of sense and used to be more common than it is today. Years ago, old hand crank Singer machines were coveted in the ocean racing fleets because they were light, required only the strong arm of a young crewmember to run and could handle most sail cloth weights, particularly spinnaker cloth.

Sailrite is a great one-stop source for all of the tools you will need for making onboard sail repairs and they have really helpful instructional videos on their website that will help you grasp the techniques sailmakers and canvas experts use when making repairs. They also sell high quality sewing machines. Carrying a sewing machine aboard a cruising boat makes a lot of sense and used to be more common than it is today. Years ago, old hand crank Singer machines were coveted in the ocean racing fleets because they were light, required only the strong arm of a young crewmember to run and could handle most sail cloth weights, particularly spinnaker cloth.

The electric-powered machines offered by Sailrite are designed for sewing sails and heavy canvas so they are powerful. For use at sea, you need to be able to plug them into 110 volts either via an inverter or a genset. Yet, when you have a long seam to repair or you need to sew in a patch over a large tear, a good sewing machine is the right tool for the job. Check out the Sailrite website at www.sailrite.com.

The best repairs are made with the right tools and some practice. Occasionally, you may find yourself without one or the other. If I really needed a sail to get somewhere because of extended distances, lack of diesel fuel or other extenuating circumstances, I probably wouldn’t let either the lack of a proper sail repair kit or lack of experience stop me. Please don’t tell any sailmakers where you got the idea, but if forced to do so, I might even stoop to using Duct tape to repair a sail. Of course, it will need to be cut away later, further causing damage to the sail, but in an emergency, a lot of things will work in the short term that you may regret in the longer term. I will caution, however, that the use of 3M 5200 or rubber cement for sail repair does require parental supervision and a complete disregard for doing things the right way. But they work.

A few words to the wise would include, “take care of your sails but be well prepared for the unforeseen.” Eventually, the unforeseen will happen and having the right kind of sail repair kit and some knowledge of how to use it will serve you very well.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net