Getting from the East Coast to Bermuda can present a road full of potholes (April 2012)

It’s another Bermuda Race year. That, however, is just one of the many reasons that sailors fetch up on those wreck-strewn, reef-surrounded, sandy, and yet still hospitable shores. At times, it can be a real trial by fire to get there.

While Bermuda might be the ideal point in the Atlantic Ocean to make a stop whether you’re coming up from the Caribbean bound for New England, heading from Charleston or the Chesapeake Bay to Europe, or involved in this year’s race to Bermuda, each route has its own set of obstacles to overcome.

Typically, when planning a passage, I break down the trip into a series of hurdles. I look at the tidal conditions that I’ll expect to encounter on departure. I closely monitor the weather patterns for days prior to leaving, keeping open my option to leave early, late or on schedule, depending on the weather we’re expecting. If it looks bad, I know well in advance of departure, and I either hasten the process to get out of port and beyond the reach of the bad weather or delay my departure until conditions are more favorable. Little is gained and few friends are made by leaping into a storm pattern that blows the boat apart. A working knowledge of how to read and interpret weather information can provide a huge benefit as you try to avoid the worst and take advantage of the best that the weather has to offer.

When leaving New England, I typically expect the weather to move from west to east. That’s not always the case. Sometimes low-pressure systems are spinning up from Cape Hatteras, heading northeast south of Cape Cod. Other times we may have to deal with a “back door” low-pressure system spinning around in the North Atlantic that decides to make a reappearance from the east. And still other times, a “cut off” low pressure system may be stalled in the western North Atlantic, holding up the weather systems’ parade. But in most cases, the lows and fronts will approach New England from the west. Those meteorological movements can be monitored on maps, using satellite imagery to get near-real-time information about the frontal approach, or by staying informed via VHF, SSB or online text forecasts. The information is widely available to help you avoid heading out into the teeth of a raging Nor’easter as you begin your trip to Bermuda.

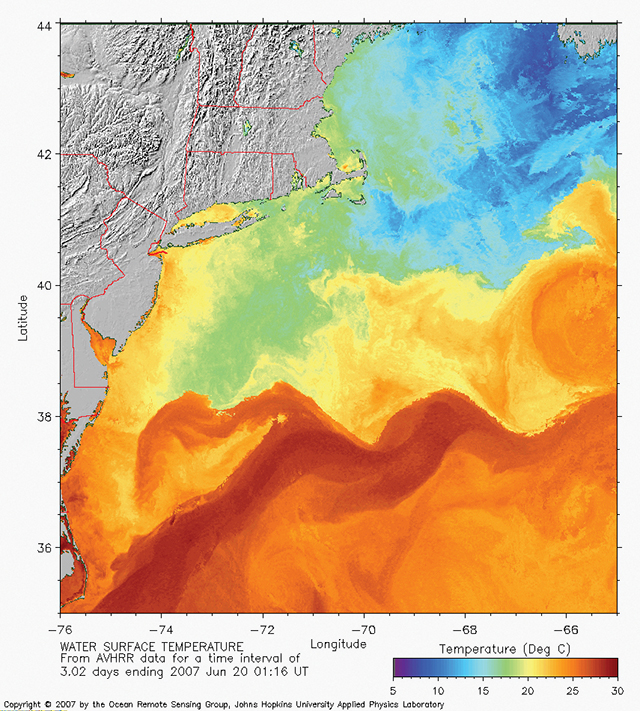

From the East Coast of the U.S. to Bermuda, you’ll have more to consider than just the weather, of course. One of the major hurdles encountered along the way will be the Gulf Stream. You’ll need to give careful consideration to your strategy about how to approach and cross that major oceanographic feature. Currents can move between 2 and 5 knots in some places, and the meandering warm water stream will definitely have a strong influence on your progress. In addition to the actual speed and direction of the current affecting your own speed over the ground, the current will influence the size and shape of the waves. If winds are strong and pitching against the strong current, the waves will be particularly steep and high. Strong northeasterlies can turn the Stream into a living, waking nightmare. Conversely, strong to moderate winds from behind with the current moving in the same direction can turn the passage into a sleigh ride, ideally with warm, sunny skies dotted by small puffball fair weather cumulus clouds.

From the East Coast of the U.S. to Bermuda, you’ll have more to consider than just the weather, of course. One of the major hurdles encountered along the way will be the Gulf Stream. You’ll need to give careful consideration to your strategy about how to approach and cross that major oceanographic feature. Currents can move between 2 and 5 knots in some places, and the meandering warm water stream will definitely have a strong influence on your progress. In addition to the actual speed and direction of the current affecting your own speed over the ground, the current will influence the size and shape of the waves. If winds are strong and pitching against the strong current, the waves will be particularly steep and high. Strong northeasterlies can turn the Stream into a living, waking nightmare. Conversely, strong to moderate winds from behind with the current moving in the same direction can turn the passage into a sleigh ride, ideally with warm, sunny skies dotted by small puffball fair weather cumulus clouds.

As you approach the Gulf Stream, small fair weather cumulus clouds may be among the first signs that you’re getting closer to the warm current. There are, of course, a number of websites that will offer infrared images of the Gulf Stream to help you determine its location. And among other means of identifying its whereabouts, altimetry data will confirm its location by measuring the height of the water from space. Amazingly enough, the height of the water can vary as much as three feet or more, depending on the current, and satellites have been designed and equipped to measure those height anomalies. From the deck of your boat, however, other signs may include Sargasso weed streaming across the water’s surface strung out in long patches. The wildlife will change as well. Portuguese men o’ war will become more numerous, and it might be a good time to deploy the fishing poles if you’re not in a hurry. Tuna, dorado, flying fish and other species often like to cruise through the warmer water.

The warmer water has other implications, as well. The warm air rising off the surface of the water will not only create those little puffy clouds, but it will also increase the likelihood of lightning and thunderstorms at night, adding power to any squall line that may be approaching ahead of cold fronts. The Gulf Stream definitely deserves respect, and it will get your attention.

Passagemakers heading up to Bermuda from the Caribbean usually face a different set of circumstances. The weather is usually suitable for departure. It’s true enough that the wind may be blowing out of the NE, but usually a course can be set that will help you get north or NNW, allowing you to fetch Bermuda as you get a bit further into your trip. If you start out in light conditions, you may need to closely monitor your fuel consumption so you don’t get stuck in the North Atlantic subtropical high pressure system that often hangs around Bermuda in the late spring and summer months. There’s a reason some people call it the “Bermuda High,” and you may not want to be drifting 50 miles from St. Georges while others are ashore knocking back Dark & Stormies.

Of course, light air isn’t only encountered when coming up from the south or heading east out of Charleston. The sub-tropical high-pressure systems in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres circle the globe, roughly between 25 and 35 degrees north and south latitudes. The highs morph and change shape and location based on season and the proximity of the encroaching low-pressure systems. Without getting too technical, all of that, of course, is influenced by upper atmosphere conditions, driven by the jet stream and indicated on the 500 mb weather chart.

Weather is a huge 3D evolving and ever-changing situation. If you’re going out in it, you need to be aware of how weather works and how it’s going to affect you and the people you’re with. Bermuda is a jewel in the middle of the Atlantic. Getting there can, at times, be a trial by fire, but the reward is a treasure at the end of the road.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net