The steps a sailor took to fulfill a dream (published June 2014)

The plan to make an expedition to Antarctica started brewing in January, 2008, when I began steadily building Quijote, a 12 meter steel yacht based on Bruce Roberts’ Voyager 388 with modifications to the deck, pilothouse, keel and interior.

I launched Quijote in September 2010 and initial sea trials were around Buenos Aires, then to Uruguay, and finally the biggest test was a trip to Brazil. As the miles passed below the keel, new needs became apparent and once back in Buenos Aires after the six-month shakedown trip, I started on them before heading south. The improvements included the installation of a broadband radar, four reels on deck for 110 meters of floating lines each, a hard aluminium spray hood and the installation of a second antenna for the SSB radio. I also added more anchor chain to give a total of 135 meters, completed the installation of the stove and completed the supply of food, which turned into a stowing challenge.

In early December, my wife Laura and I left Buenos Aires for Ushuaia, the southernmost city in the world, and our starting point of adventure for the White Continent.

THE CREW

The initial idea was to have a crew of four or five people, preferably four due to space, but five was more conservative so if someone dropped out we’d still have enough. Laura and I started brainstorming candidates, which was not an easy task. We needed crew who knew how to sail, who could spare six weeks, and most importantly, whom we actually wanted to spend six weeks aboard with! Having enough free time was of the utmost importance to us, as we didn’t want to be forced to make bad safety decisions just so a crewmember could make a flight.

After long lists were narrowed down, we invited two Argentine women, Pato and her twin sister Myriam, and Erik Østrem, a Swedish friend who is very fond of adventures. Just before the trip started, Myriam had to pull out for work reasons, which left us with the four we had originally planned. But, we, of course, were quite sad to lose a crewmember at the last minute.

DEPARTING FOR THE DRAKE

In the last week of January, Pato and Erik arrived in Ushuaia and the crew was complete and Quijote was ready to set sail. Our final step, though, was to wait for a weather window that would allow us to cross the infamous Drake Passage.

Much has been said about Cape Horn and the Drake Passage over weather unpredictability. And it was precisely this that kept me from sleeping many nights. As we waited and days passed by, I had the opportunity to compare weather forecasts against reality and finally came to the conclusion that we were going to be safe, as the forecasts and the reality were matching up. We downloaded the GRIB files daily via our Iridium phone connected to our PC and opened the files using the zyGrib program.

After waiting several days in Ushuaia and then a few more in Chile in Puerto Williams and Puerto Toro, we departed to cross the Drake. It was lumpy, but a complete success. And we found the weather forecasts to be precise to within three hours for both the wind strength and direction.

We learned that we were often too cheap on the Iridium airtime and missed out on key weather details. To save on Iridium connecting time we had set the forecast intervals to every 12 hours, but during that time a whole storm can come and go. We then decided to download with data intervals of six hours and a projection of four days. We also used our Iridium connection to send and receive emails, update Facebook, the blog of Quijote and update our position on a Google map, and were usually able to accomplish this in less than two minutes of connection time.

Our Iridium phone also allowed us to receive free text messages from friends and family sent via the Iridium website. Receiving those messages became a breakfast ritual and all the messages were saved from the previous day until breakfast when everyone was gathered around the table. These became our source of news from family and friends, but also our source of news from the world and other bits of information friends decided worthy to send us.

KEEPING WATCH FROM THE PILOTHOUSE

The navigational watches on Quijote are perhaps a bit different from the average 40-foot sailboat. She was designed with a pilothouse and steering control inside. Years of being cold and miserable on crossings of the Rio de la Plata dictated having an inside steering position. However, in addition to comfort, it’s also a safety feature when crossing large and dangerous bodies of water. We made full use of the pilothouse and the pilot’s seat, from where we have access to all the instruments and a clear view of the bow.

At first, Pato took a while to adapt to this system and she often wanted to go outside. Soon, as the outside temperatures dropped and the waves rose and swept across the deck, she discovered the benefits of keeping watch and running the boat from inside the pilothouse. Of course, one still needs to take a peek and see how everything is on deck, but, for safety reasons, it was best to stay inside and was quite difficult to look ahead from a cockpit swept continually by sea spray and pounded by the cold wind.

For the four of us, we established three-hour shifts, leaving nine to rest, so each crewmember had their own fixed routine of work, rest and food. This allowed enough time for each person to make an attempt at getting a good amount of sleep.

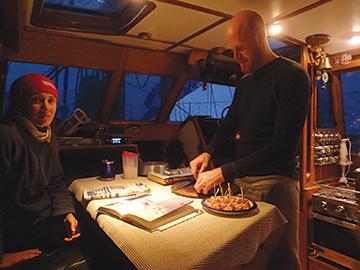

MEALS

We struggled with planning for meals and learned much in retrospect. We ate much less than expected, but I gained weight. Often in cold weather, one increases their caloric intake and can even double it, however, the full doubling was not true in our case. The good heating on Quijote helped reduce the need for a huge increase in calories. In addition, the temperatures that we experienced always hovered just around freezing. Perhaps with colder temperatures or windier conditions our experience and needs might have been more pronounced.

Living, and more importantly, eating, as a group can have its challenges when trying to keep everyone happy and we proposed that each crewmember could bring one snack to call their own and not be obliged to share—so we wouldn’t have to hide in our bunks to eat candy! Laura brought salty-sweet Chinese rice crackers, Pato enjoyed the evenings with her special liquor, Erik brought some Swedish liquorice candies that did not interest anyone other than Erik, and I did not bring anything special because I knew that the bowels of Quijote were packed with several kilos of chocolate.

We turned off the refrigerator once we arrived in Antarctica. It made no sense to “eat” amps to cool the refrigerator to 8 degrees when outside it was hovering around freezing. A plastic basket became our “daily refrigerator,” which we placed outside next to the companionway. The rest of the items that we needed to be kept cold were placed in the bilges.

In Ushuaia we found vacuum-packed meat that was good for two months. These were the perfect solution for us. We brought 37 pounds of rib eye and rump roast, packed in 2.2-pound bags, which lasted the whole trip.

We assigned roles to each crewmember prior to the trip and Erik gladly became the expedition chef. We were grateful, and he more than spoiled us (think beef bourguignon, goulash, curries, etc). In addition to Erik cooking, the plan was that once a week each of us would cook something to give him a rest. Laura prepared Pad Thai, among other oriental dishes and Saturday night became Captain’s Pizza Night when I had my turn in the galley. Pato offered to do the dishes each day on the condition of not cooking during the trip. We all accepted the deal immediately.

PROBLEMS

No trip is perfect—and if a captain tells you so, he is not telling the truth. We faced our share of problems, all of which we fortunately managed to solve, and from which we were able learn something.

The night before entering the South Shetland archipelago the primary fuel filter got blocked due to water. This caught my attention because on Quijote we have several filters: between the main tanks to the daily tank there is a water filter separator so the diesel reaching the daily tank should be water-free. The daily tank is located in a heated area, it is made of plastic and I never let it get empty beyond half, so the risk of condensation should be minimal. Nevertheless, the primary filter in-between the daily tank and final filter got blocked. The solution was to purge the daily tank and the primary filters every day and we never had the problem again. All of this must have been due to condensation given the temperature extremes between Quijote and the outside air.

Another unexpected problem came when we set sail from Foyn Harbour after two days of heavy snow. Because the sea temperature was at or near freezing, the surface of the water was covered with half an inch of snow, which continued as a slushy consistency below the surface. The snow even started forming the famous “pancakes.” This slushy snow managed to block our sea strainer even though the intake is located about 70 cm below the waterline. As the engine uses a keel-cooler system, the seawater is only used to cool down the exhaust system, but we still had to stop the engine for a minute to unclog the filter.

On another occasion a much more serious and scary problem occurred. At every anchorage we used four shore ties in addition to the anchor. Many boats use wire slings around the rocks on the shore and we used large strops normally used in crane lifting operations. We found them equally strong, but much easier to handle. One night after a tiring, frustrating search for a good spot to spend the night, we decided that two lines to shore were good enough. It was the first night we ever decided to do this during the trip and exhaustion and hunger had clouded our thinking.

Just before midnight, one of the strops slipped off its rock, leaving the boat attached by only the stern line. We heard the keel touch the bottom and quickly realized that we had ended up on the leeward shore. We were in a very protected cove and the shore was very steep and rocky. This meant that we were merely leaning up against the rocks and it was very easy to remove the boat from its unfortunate position. We launched our dinghy, passed the rope to a different rock and then winched the new line to pull us off the rocks. Fortunately, the boat was not aground; its keel was merely “alongside” the shore. We were lucky, but the potential risk of this situation was very high. From then on we always used four moorings, no matter how tired we were or how safe it seemed.

Our heater also caused a few problems. Whenever we used the engine, the heater went off and we thought this was due to the diesel engine sucking a lot of fuel, most of which then returned to the tank. However, I believe that when it was sucking the diesel, it “stole” the fuel from the stove as they shared the daily tank. Once in Antarctica it was not an issue, as we stopped the stove during the day and we were not motoring at night. I had to address the problem to make sure we were ready to cross the Drake on the way back when we might be using both at the same time. We solved this issue by making a dedicated tank for just the heater.

PASSAGE PLANNING

The actual sailing in Antarctica, as far as route planning was concerned, was much easier than it may seem, which of course comes with many stars and asterisks. I say easy, as there is minimal choice due to the lack of safe and accessible harbors. The lack of choice may make the initial planning simpler, but it unfortunately becomes less so when those options disappear due to weather or sea conditions.

Many of these sheltered spots (again, sheltered is relative down in Antarctica) are located no more than 40 or 50 miles apart, making them accessible in a day of sailing. Once leaving the previous night’s location, the difficulties begin. Ice conditions can often make what calculates out on paper to be a 10 hour, 50 mile sail into a 14 or 16 hour slow day of maneuvering at one knot through the ice. At times the ice made it impossible to continue to certain places.

Due to the potential for ice during the day and the resulting loss in speed, we always tried to sail at first light to have the whole day ahead, no matter how close the next place was. Had we gone earlier in the season, with nearly 24 hours of daylight, this might have been less of an issue, but by mid-February, there was already six to seven hours of darkness.

One of the “easy” choices was the journey between Deception Island and Foyn Harbour, a distance of about 120 miles without reliable anchorages or alternatives. We attempted to stop at Cierva Cove, about two thirds of the way along the journey, but the high amount of ice hinted otherwise. By the time we determined it was a “no go” at Cierva Cove, there was only two hours of daylight left and 30 miles to go to the next potential safe anchorage. I was not happy with the situation we were in—we were too far to make it before nightfall and sailing in the dark was out of the question due to the potential of hitting ice. Our solution was to drift overnight in the Gerlache Strait and hope that we drifted along with the ice rather than into it. We took watches to keep an eye on the radar for larger chunks of ice and were lucky to have a very calm night. The Gerlache can be very rough due to wind, waves, ice and the combinations thereof, which can lead to an unwelcome nightmare. Fortunately, this was the only night while in the peninsula that we “sailed,” as the risk was just too high.

QUIJOTE & SCIENCE

In addition to exploring and discovering, we wanted to do more than just gaze at the wonders around us, which can feel like a selfish endeavour. With a geology background, Laura was in charge of the science for the trip. Quijote partnered with the non-profit Adventurers & Scientists for Conservation (ASC), whose mission is to bring science to citizens, and specifically to partner adventurers with scientists. Scientists often need basic data from faraway places, but don’t have the funding or time to go everywhere they want or need. Adventurers are going to these places and can often make basic observations or collect simple data that the scientists can then use. We partnered with a scientist in Alaska to make observations for two projects, one involving penguins and another involving whales. The penguin research was on “lateralization” in penguins and how they subsequently relate to each other and the whale project was on the potential ability of baleen whales to smell and how they might use that ability for finding food.

These two projects required us to make only observations, with no interaction or interference with these animals. Both projects forced us to observe these animals in a deeper manner than we would have if we were merely “tourists.” Once back from the trip, all data that we collected was sent to the scientists.

FINAL REFLECTION

Antarctica is an achievable dream. But like any dream it involves work and dedication. Any boat thoroughly prepared can go, as many have proven over the last decades. But there are two key words—thoroughly and prepared.

No matter how prepared the boat and crew are, there will always be many things that only the captain knows, feels and thinks. It is not easy to explain, as only those who have been in command understand the weight of this responsibility. For a boat to go and return home safely means long nights of anguish and doubt as well as non-stop thinking, planning and running through everything in your head. It is not enough to know or to be told “all is well,” you have to be (silently) pessimistic and distrustful. Nothing guarantees success, but as Amundsen said on his return from the South Pole: “Victory awaits him who has everything in order, luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck…”

Personally, I am proud to have built and prepared a sailboat that left port heading for the White Continent and returned with all its feathers more or less in place. I fulfilled the dream and left a lifetime of memories to four adventurers.

Federico Guerrero has been sailing with his family since he was 12. When not sailing and working on Quijote, he works on merchant ships where he holds a Masters Unlimited License. He lives with his wife Laura on Quijote in Ushuaia. He receives questions and comments at www.SyQuijote.com.

Statistics & Curiosities

Statistics & Curiosities

• 1,750 miles sailed round trip from Ushuaia to Ushuaia.

• 200 engine hours. With the exception of two occasions, all navigation within the peninsula was motoring, either due to total lack of wind or due to its direction on the bow.

• 800 litres of diesel consumed (leftover 400). We used regular car diesel rather than Antarctic diesel, since the temperature in the summer time does not require special fuel—although it is very important to have a daily tank in a heated place to prevent the diesel from becoming waxy.

• 1,000 litres of water used for drinking, cooking and a short shower. We never re-supplied while down there and dishes were done with seawater.

• South 65 º 15’ was the most southerly latitude reached, at Vernadsky Station.

• -3 °C was the lowest temperature recorded.

• 15°C, the interior temperature of Quijote during the day without the stove, provided we had some sun. The pilothouse has all double glazed windows and acted as an excellent greenhouse!

• 35 knots, wind intensity peak in the Drake Passage and Antarctica. Although another sailboat sailing not far from us recorded gusts of over 50 knots.

• 2 tons of snow was what we got on deck one night in Foyn Harbour (considering the fresh snow was weighing around 200 kilos per m3).

Safety & Permits

Safety & Permits

Three of the four crew work in the offshore industry and thus it was logical that we maintain the same safety-related practices while in Antarctica. Here are some that we felt were quite successful:

• Before each operation, such as mooring or un-mooring, we did a tool box meeting where we explained the task, debated the options, defined the roles and cleared up any doubts. We also reviewed the risk with the operation, such as winds, currents, looming darkness, etc.

• At the end of the activity we held a debrief to search for areas of improvement on the next operation.

• We always did the work under the slogan of “Safety First.” This meant that our decisions were guided by safety and nothing else—not going a bit further on a hike, nor leaving Antarctica just to get back for a flight. This also meant that we all wore inflatable life vests whenever we went on the tender—it wasn’t really necessary while sailing in the peninsula as the seas were flat calm, but safety is for the unexpected. While sailing, if the seas were rough we would stay inside the pilothouse or in the fully enclosed cockpit, from where you could reef all the sails and adjust the sheets.

• In terms of preparation for this trip I attended the Antarctic Navigation course put on by the Argentine Navy. For two weeks they provided me with abundant information and experiences for navigation in Antarctic waters.

• With regard to the formalities, we had to submit an environmental impact statement which is required by the Argentine Antarctic Institute. This was our permission request, based on the requirements of the Madrid Protocol.

Recommendations & Lessons learned

Engines are indispensible: Exploring Antarctica can be done almost purely by sailing, as many explorers have done in the past. However, having an absolutely reliable engine with ample power and plenty of diesel capacity not only made our life much easier but it also allowed and encouraged us to explore more and get into places that would otherwise not be possible.

Engines are indispensible: Exploring Antarctica can be done almost purely by sailing, as many explorers have done in the past. However, having an absolutely reliable engine with ample power and plenty of diesel capacity not only made our life much easier but it also allowed and encouraged us to explore more and get into places that would otherwise not be possible.

Having a good rubber-bottomed tender with a reliable outboard engine, along with good handheld communication: We specifically used this for sending the tender ahead to explore tight and shallow anchorages and then getting the lines to shore. We found the rubber bottom to be better than a hard bottom, as it is much lighter. Our tender did quite well even with the ice we encountered. Our boat is PVC, not hypalon, and did very well.

Sending someone up to the spreader as a lookout for ice made ice navigation much easier and was often necessary: From sea level everything can look like a big white wall, but with a few extra meters you see hope!—6 meters proved to be enough to find the way.

Communicating with all vessels crossing our path: The exchange of information was very important to learn about ice conditions or specifics of crossing a small strait. However, we never took any information as an absolute truth—ice conditions change so fast that what was true yesterday will probably be false today.

Having a good heater, and if possible one that can be on 24 hours: We found it important to keep it on all night—if it’s turned off at night there is a risk of condensation when the temperature drops below the dew point and this continued condensation and flux in temperature every night is not good for everything and everyone onboard. Our Refleks heater in pilot mode consumed a few litres per day, was silent and did not consume electrical power. It also always worked. The important part of the diesel heater was spending time and money to make a good chimney.

We did not use any special clothes or super expensive waterproof clothing. We used good Merino wool long underwear, one or more layers of fleece, and then some windbreakers, often doubled as our waterproof outer layer. Waterproof mittens with liner gloves were a must, as was a fleece neck gaiter and wool hat. We often wore two pairs of wool socks and a good pair of rubber waterproof boots. We used the MuckBoots that are insulated for cold climates. It’s amazing how warm you can have your feet with proper footwear. Obviously if one does not have the protection of a pilothouse then the requirements might change a bit, especially while crossing the Drake.

Putting the mooring ropes on reels made life infinitely easier.

Navigational Charts & Software

Navigational Charts & Software

During our trip we used a variety of devices and charts for navigation. At the start of our trip we used the Argentine chart of Deception Island, which is the best at the moment since it is new, and WG84. For the rest of the Peninsula we also had the Argentine charts but as a reference only. In the Peninsula itself we used the United States charts, as they compile information collected from hydrographical surveys from Argentina, Chile and UK, all on the same chart.

Our system while underway was to plot a GPS position at least once an hour on the chart. We then corroborated the position with bearing and distance from the radar. We were impressed with the chart accuracy, considering that the scale of the charts does not allow great detail.

We also used the free Open CPN software with CM93 vector charts. The performance was satisfactory. It usually gave us a decent position, and we treated it as another aid to navigation just as anywhere in the world where you navigate in restricted waters. We used the software more for passage planning, distances, timings and ETA’s. For this purpose it did quite well.