A cruising dream realized in the wake of Odysseus (published April 2015)

In a sense, I had been preparing most of my life for my voyage to Odysseus’ island of Ithaca, which hugs the western coast of the Greek mainland in the Ionian Sea. As a young boy, I was fascinated by mythology and scoured our venerable World Book Encyclopedia for articles on the Greek gods and their myths. I read the Iliad and Odyssey as a youth. As a diplomat, my career repeatedly took me to the eastern Mediterranean, and with my wife, I built a house near Paphos on Cyprus not far from the goddess Aphrodite’s birthplace.

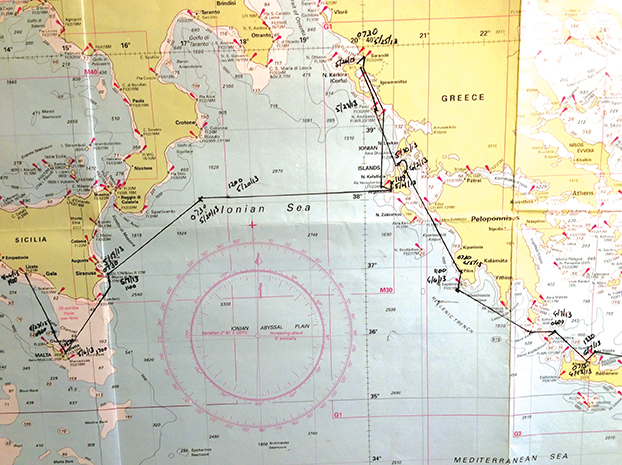

Later in retirement mode, I crossed the Atlantic in my Pacific Seacraft 34 Panope in 2011, and I filled some of the long night watches by listening to a BBC dramatization of Homer’s account of Odysseus’ journey home from Troy.

My way to Ithaca had indeed been long, but in May of 2013, I found myself on Malta midway across the Mediterranean and within striking distance. I was joined by Mike Niemi, a friend I had met sailing in the Caribbean. Mike, bearlike and with an untamed beard, also owned a Pacific Seacraft 34, which he berthed in Man-O-War Cay on the Sea of Abaco, Bahamas. He had made several passages with me in the Med and was a valuable crew. Not only nautically clever, he had spent a career at IBM on the digital frontier. At home in the Bahamas, he had become a historian of Abaco boatbuilding and was helping Man-O-War develop its museum and website.

I had hauled the boat in Malta to re-paint its bottom, change zincs and lube its Variprop. The Maltese have a long history of working with seafarers, and once I appreciated fully their expertise, I determined to exhaust my “to do” list. The skilled hands at Manoel Island Yacht Yard soon fit a new dripless shaft seal, refurbished my life raft and tuned my Yanmar diesel, which they tested on the hard after reinforcing its blocking and rigging a water supply.

ONWARD TO ANCIENT SYRACUSE

With confidence in the refitted boat, Mike and I launched for ancient Syracuse in Sicily. The forecasters at our usual weather site predicted a smooth passage. Sure we were crossing one of the most trafficked bodies of water in the world—the Malta Channel—but I had recently installed a Watchmate AIS transponder to monitor shipping traffic and transmit our position to ships. The seas were choppy leaving Malta’s Grand Harbor, but we welcomed the westerly, and for several hours advanced as the winds increased.

In late afternoon, however, my mental inventory for the night felt increasingly uncomfortable. The winds were in the mid 20s, the seas choppy and the ship traffic heavy. If the winds increased further or the sea state deteriorated, our margin for error might erode rapidly. It seemed to me that both the wind and the waves were being funneled by the Sicilian and Malta channels and likely to exceed the forecast. It was time to reef.

As I went forward, I noticed that our tender’s oars, stowed in slots and lashed to the cabin’s top, had come loose and were askew. I made a mental note to secure them once I had finished setting our sails for the fast approaching night. A simple task proved devilish, as the gooseneck hook was too flush with the mast, and I had difficulty fitting the reefing cringle over it. The effort was made more problematic by the pitching deck. I had just enough daylight to finish the job.

My sense of victory was short-lived, though, when I returned to the cockpit and noticed that one of the oars had washed overboard. I hadn’t taken the “stitch” in time! Our night passed without further incident, but Mike resolved to research better weather programs to reduce future surprises as much as possible and I needed to replace that oar to use the tender for which we had no motor.

Morning found us approaching Syracuse on Sicily. My repeated attempts to reserve a berth at the municipal marina alongside Ortygia, the ancient city, had proved fruitless. But Emi Sorriso, a Sicilian friend from Marina di Cala del Sole in Licata, had intervened on my behalf with more success. (In my experience, marinas in the Med run the gamut from modern, impeccably organized ones where arrangements are easily made via websites or e-mails to basic municipal marinas where reservations are hit-or-miss, but space for transients can usually be made. Emi’s in Licata had approached perfection while our marina in Syracuse was at the “informal” end of the spectrum.) We docked handily and went through the minimal formalities I found prevail in Italy.

Next we had a rendezvous with a friend, Nicholas, a scholarly Brit with fluent Italian who now calls Rome home. He had made a career in the preservation of historic buildings and sites with the Getty Conservation Institute and the International Centre for the Study of Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM). Who better to serve as our guide in Syracuse’s ancient city, with its winding streets full of historic churches and palazzos?

While we kept an eye out for Nicholas, Mike and I had begun to explore the outskirts of the marina. There were a number of stands selling drinks and snacks and I introduced Mike to lemon granite—the shaved-ice treat that the Italians alternate with gelato, their famous ice cream. The Sicilian lady who operated the stand took great pride in her granita, and took offense if even the slightest bit was left in the dish. We must have been pre-occupied with this discovery because when we returned to the boat we found Nicholas waiting nervously, having evaded our look out.

With Nicholas as our guide, we set out to discover Syracuse. Founded by Greeks from Corinth in about 733 B.C., Syracuse boasts many myths and much history. A spring-fed pool near the seafront is associated with the nymph Arethusa, who escaped the depredations of the river-god Alpheus by navigating an underground river that by legend connected Greece to Syracuse. Nearby the central cathedral not only occupies the site of an ancient temple, but, as Nicholas pointed out, incorporates columns from that temple into its walls. On the outskirts of the city in an archeological park is found an ancient quarry, nicknamed “Dionysius’ ear” for its appearance and acoustical properties.

Nicholas suggested that its unusual structure might be explained by quarrymen working deeper and deeper into the stone face to escape Sicily’s blazing sun. Legend holds that the tyrant Dionysius the Elder exploited the acoustics to spy on his enemies. History confirms that the site imprisoned the Athenian warriors who were taken prisoners in the disastrous expedition, prompted by Athenian hubris in 414 B.C. In the ancient theater nearby, the Festival of Greek Drama opened that night with another study of hubris—Oedipus Rex. We joined many Syracusans in attendance and later in the marina were invited aboard an Italian boat for an after-theater party.

Each morning thereafter, Nicholas, Mike and I convened for cappuccino and cornetti in a popular café by the ruins of the forum. The staff soon accepted us as regulars bringing our breakfast without bothering to take our order. Mike opted to visit a museum dedicated to Syracuse’s great mathematician and engineer Archimedes while my priority was Caravaggio’s famous painting of Santa Lucia in her basilica. The patron saint of Scandinavia ironically was a Sicilian girl slain by the Romans for her faith. Caravaggio depicts her as a slight young martyr flanked by hulking Roman executioners while a stunned crowd looks on. Roman power has long since dissipated whereas Santa Lucia’s attraction has spread through much of Europe. The following night on her feast, the Syracusans carried in procession a silver statue of the saint—a sword piercing her neck—throughout the old city.

Sicilian cuisine, made famous in the Montalbano detective mysteries, was generally superb. The Ambasciata d’Ortigia, a family-run restaurant, was our favorite and merited a second visit. When praised for their seafood appetizers, pastas and entrees, our charming waitress made one request: write a review on Trip Advisor—which I did. Later in a touristy place, however, I made the mistake of eating a seafood risotto that appeared within minutes of my order. “Never eat a seafood risotto that arrives sooner than 20 minutes after ordering,” Nicholas said in disapproval, “because you are eating a left over!” That night and for days to follow, I alternated between my bunk in the V-berth and the head as I recovered from food poisoning.

Mike spent his time more productively. My lazy jacks had been mended several times and needed replacement. The set I ordered from West Marine proved flimsy. Mike suggested he could do better by splicing a length of suitable line, and he did so handily. He also researched weather prediction programs—in his IBM mode—and settled on PredictWind as worth a try. I would have simply downloaded the application. Mike, a member of the programmers’ community, contacted the company and worked a deal whereby he would get their latest version for real-world testing. I am not sure any money changed hands and our missing oar was left unaddressed.

OUT OF THE EU

Recovered from my food poisoning, we set off. Our destination was Saranda, the Albanian port across a bay from Corfu. I had been in the European Union for almost a year and a stay of 18 months would subject Panope to a hefty tax. We headed out on a course of 45 degrees and crossed the Straits of Messina with wind and waves mounting. The high winds and rough seas prompted me to rig storm sails for the night, and morning found us off the boot of Italy making only a few knots in heavy seas.

We had not topped up with diesel in Syracuse so motor sailing to Saranda was a dubious option. One possibility was to motor due north to the Italian port of Crotone and refuel there. Alternately, we could take advantage of the northerly and sail across the Ionian Sea to Cephalonia, which we opted to do. On a reach, the passage was quick and relatively comfortable although our small stainless-steel tiller, rigged for the autopilot, cracked along the way and we set up the Monitor steering vane as a better, more rugged alternative.

Within 28 hours, we were heading into the well-protected port of Argostoli, made famous in Louis de Bernieres’ Corelli’s Mandolin. A few boats were anchored in the harbor, but without a working tender we had to find space on the city quayside. Across the way, restaurants and shops beckoned. Several blocks farther was the commercial harbor with the Greek Coast Guard office. None of our sailing neighbors were in a hurry to do customs formalities so we too adopted a laissez faire attitude.

I set out purposefully with our remaining oar in search of a mate and with our broken tiller. Like Odysseus carrying an oar on my shoulder, I inquired at nearby chandleries. Aluminum replacements could be found, but not the real thing. For the tiller repair, I was directed to the industrial area on the far edge of town. With my basic Greek, I asked my way and finally arrived at a machine shop after a couple hours of walking. The machinist studied my tiller. It could be fixed and should be left. I pleaded in my best Greek—off a boat, the distance, on foot…parakalo! The Greek struck a chord, and he agreed. Twenty minutes later I was on my way with half of my immediate problems resolved.

Back at the harbor, the word was spreading that a mighty storm was on the way. Mike and I prepared: we detached a board from the lifelines to which we had lashed water jerry cans, and used it to reinforce our fenders and shield Panope from the concrete quay. Farther down, a serious drama developed as a large sailboat had dragged its anchor and was about to be blown into another at the quay. To make matters worse, the first boat had a line fouling its propeller. Some went in search of the Greek Coast Guard for a tow, but that help was not to be found. Others fended off. Someone called for a diver. In the end, the first boat’s captain dove and managed to free the prop. We returned to our snug cabin to wait out the storm.

After a day or so, the seas settled. Mike and I headed north by northeast under sail for Albania. Our passage hugged the Greek mainland with the large island of Corfu to the east. We were not sure what to expect in Albania, a country long isolated by communist rule, but newly free. For help, I referred to a Seven Seas Cruising Association bulletin that identified Agim Zholi as a trustworthy port agent. An e-mail form Cephalonia had established a rendezvous, and Agim was at the dock to meet us. For a modest sum, he handled all our formalities and even provided an Albanian courtesy flag.

A quick tour of the town evidenced that we were clearly no longer in the EU. The buildings were shabby and the prices were low. Judgments are relative, however. Later that night, we joined up with an American embassy group visiting from the capital Tirana. They were in Saranda for a holiday and assured us that this “resort” would soon be overwhelmed by vacationing Albanians.

With our excursion outside the EU suitably documented, we launched the next morning for Corfu, a passage of a few miles. By tradition, Odysseus had been washed ashore there after Poseidon destroyed the raft he had built to leave Calypso’s enchanted island. Naked and exhausted, he was discovered by the Princess Nausicaä and taken back to the court of Alcinous, king of the hospitable Phaeacians. In that court, Odysseus recounts his tale of travel and travail.

THE ODYSSEY CONTINUES

Corfu still welcomes its visitors. With our Albanian documentation in hand, we were keen now to formally enter Greece. Our Mediterranean Atlas promised that we could do so conveniently at the Gouvia Marina. In fact, only EU boats can clear customs there. The friendly Greek official directed me, an American, to the Commercial Port. I asked Mike to join me, and we hopped a bus into Corfu city. A few queries brought us to the ferry terminal where we waited for the Greek authorities to quickly process hundreds of ferry passengers. Thereafter, I was taken into a little room where huge legers lived. I supplied my information, paid a modest fee and was rewarded with a “transit log.” Finally, I had formally entered Greek waters. Unlike in Italy, where one comes and goes with minimal formalities, in Greece, the authorities expected one to check in at each port and secure an entry and exit stamp.

We then proceeded to a separate location for passport formalities. Luckily, Mike was with me for the required identification and computers made short work of our entries. We dallied for a few days in Corfu, a delightful city with excellent food and friendly people. I haunted the chandleries and workshops in search of my missing oar, but no joy.

Corfu is the ideal launching site for Ithaca. Homer tells us that the Phaeacians were great seafarers as well as great hosts. On hearing Odysseus’ tale of woe, King Alcinous not only presented him rich presents, but commanded that a boat with a fine crew take him safely home to Ithaca. Alas, by doing so, the Phaeacians offended Poseidon and upon their return, the sea god transformed the ship and crew into rocks, which are featured off the coast of Corfu harbor today. My insurance against a similar fate? I had carefully chosen my boat’s name: Panope was a sea nymph, daughter of Poseidon. Surely, a father’s love protected me from calcification.

Odysseus had raced home. Mike and I took our time. First, we put in at the charming port in Paxos. Moored at the town quay, we received the well wishes of many locals who were impressed that the boat had come all the way from Washington, DC. Then we pushed on to Fiscardo on the northern tip of Cephalonia. In Saranda, we had made room at the pier for a large power yacht with a crew of four fast friends enjoying a mid-life escape. They swore Fiscardo was the best harbor in the Ionian, and they seemed to know something about having a good time.

We arrived in the small harbor near sundown to discover for the first time in Greece that one could not assume a mooring, especially in charter waters and at a popular spot. Other latecomers had dropped anchors and taken a long stern line ashore to tie off. Lacking an oar, anchoring was not an option for us. Finally, we spied what might be an unused space at the dock next to the shore. Large rocks on the bottom there were a good reason to leave it vacant. With no alternative, and a relatively shallow keel of 4 feet 11 inches, we elbowed our way in—to the understandable annoyance of some young Greeks who thought their boat occupied all the usable space thereabouts. We taxed their forbearance further by asking them to take our bow line to the cleat on the dock. To mitigate the injury, we didn’t ask to walk across their boat to the dock, but rather rigged a loop so we could come and go via our tender.

The following morning we awoke for coffee in a nearby café and were pleased to see many boats departing, giving us a pick of moorings. Mike wisely suggested we re-locate immediately. We readied the boat only to find our stern anchor fouled. While a kindly wind kept us off the rocky shore, I dove to free the rode. We were soon re-located in a prime mooring next to what would become our favorite restaurant and incidentally our Wi-Fi provider.

Properly chastened by our lack of mooring options, I set off immediately in search of the elusive oar and a long, long stern line that might be taken ashore and tied off to rock or tree. My rudimentary Greek served me well enough at the nearby chandlery where I procured the line, but again found no match for my oar. Demetrius, the owner, did not want me to go away disappointed, however. So he went to the backroom and came back with a ball cap inscribed “Ancient Mariner” as well as a tee shirt marked crew. “But, I am a captain,” I protested. And, he quickly swapped the first shirt with one designating CAPTAIN in front and FISCARDO BAY 38 27’ 43” N, 20 34’ 31” E on the back.

OUR NEW CREW AND PERSONAL HISTORIAN

The island of Ithaca was now within sight so we sailed around its northern tip and down its eastern shore to the well-protected main port. We arrived on June 2, 2013—four and a half years after I had set out upon the Atlantic from Charleston, South Carolina. Although a popular tourist destination, the port provided us easy berthing in a spot very near the fishing boats. We found at hand many memorials to the great voyager and his patient wife, Penelope, but little of the Bronze Age culture so vividly described by Homer. The poet C.P. Cavafy had forewarned us: “And if you find her poor, Ithaca hasn’t deceived you. So wise you have become, of such experience…”

There was, however, a charming ethnographic museum in a little house near the center of town. In the course of appreciating its displays focused on the local merchant mariners, I heard fluent Greek, but with a foreign accent. Looking around the corner, I saw a short, young woman with glasses and pixie hair engaged in a lively conversation with the curator. When they stopped talking, I approached: “You’re not Greek, but you speak the language so well.”

“Well I should,” was her reply, “as I teach ancient Greek history.”

This was my introduction to Lisa Bendall, a scholar of Aegean Prehistory, from Oxford. In brief order, we established first, that Ithaca indeed had few remnants of the Bronze Age, and second, that Lisa had just completed her first course on sailing. An invitation to drinks aboard Panope naturally followed.

Over a bottle of local wine along with cheese and olives, we got acquainted. From California, Lisa had made a worldwide reputation as an authority on Linear B, one of the earliest written languages in the world that was developed in Crete and then spread elsewhere in the Aegean. It was associated with the Minoan culture, the myths of King Minos, his labyrinth and Perseus. It provided insights into the economy and culture of the Achaeans, Odysseus’ people, who superseded the Minoans. For a peek at the Bronze Age, Lisa suggested, the place to visit was Pylos on the outskirts of which stood King Nestor’s palace.

Now we know from Homer, that Odysseus’ son Telemachus himself made the passage from Ithaca to Pylos to interview King Nestor, who had fought at Troy, for news of his missing father. Since Lisa had just finished her sailing course, would she not want some practical experience by joining us for a similar passage? With little coaxing, she agreed to defer her return to Oxford and signed on. The following day, we set sail and arrived in Pylos within 24 hours.

As we entered its Bay, Lisa recounted for us the Battle of Navarino in 1827 when the British, French and Russian fleets defeated the Ottoman and Egyptian fleets, a turning point for sea power in the Mediterranean. So much of the Mediterranean’s history had been made on the sea or from the sea, not the land, and the historian in Lisa appreciated the new vantage sailing to these destinations provided.

Upon entry into Pylos harbor, a large sign unmistakably directed captains to check in with the Port Authority. Stripped of any comfortable ambiguity, I did so promptly. U.S. Coast Guard registration? Check. Insurance? Check. Transit Log? Check. Crew list? Check. Environmental insurance? Huh? Yes, the young Greek Coastie said we needed coverage lest our 35 hp Yanmar with its modest fuel and lubes damage Greek waters or shore. “Is local coverage available?” I asked.

“No, but just check with your insurer,” he replied. “There should be no problem.”

A call to Texas and USAA produced only bafflement, but my insurer did undertake to e-mail a copy of my policy to the Pylos port office. I began to puzzle through my options.

Meanwhile, we secured a rented car and set out for Nestor’s Bronze Age Palace, a short drive from Pylos. Lisa recounted her previous work on the site, particularly with the extraordinary cache of dining utensils in the banquet hall to shed light on Achaean customs. We arrived in short order, but at the entrance were informed that the site was closed—a new, protective roof was to be installed—which would take a year or more.

Even Lisa’s fluent Greek failed to budge the gatekeeper. Then she asked if the University of Cincinnati team happened to be on site. When confirmed, she asked word be sent to them that she and friends had come. We explored a nearby Tholos tomb as we waited, and upon coming out, one of the resident archeologists came down a dusty path and threw her arms around Lisa. Gates opened, and we proceeded on our tour.

Some areas were being covered over, but we got to see the large reception area where Telemachus would have been received as well as some ancient plumbing newly discovered. Lisa told us to pay close attention to the banquet hall. Later she took us to a neat museum in the nearby town, which housed thousands of objects from the site. As we eyed the exhibits, she explained Bronze Age feasting and de-cyphered Linear B tablets, like those in Crete, which had been accidentally preserved by baking in a destructive fire. Later we descended to a sandy crescent of beach where Telemachus could easily have landed his galley.

At dinner, talk of the Odyssey continued. Clearly, the naval aspects of the tale were quite reasonable, however, Homer’s claim that Telemachus proceeded from Pylos to Sparta to visit Menelaus and Helen was farfetched. The mountains separating Pylos from Sparta were daunting.

Far better to use the sea, and I announced that we would do so and promptly. Since we had failed to provide for pollution insurance, I proposed that Panope depart the following morning well before the port authority’s opening of business. And I proposed Chania in Crete as our destination. “My favorite city in all the Aegean,” Lisa commented. “Then come along,” I replied. Once more Oxford was postponed.

END OF A QUEST

So at 6 a.m., the captain had Panope prepared to launch. The crew was still buying provisions, and the delay left time for an act of kindness from a local Greek who had spent time the previously afternoon admiring Panope and discussing his ambition to sail. He returned and presented us with a bottle of deep-green olive oil from his farm. Lisa joined soon thereafter, and we were away—having done no significant harm to the environment.

A strong northerly sped us on our way. To better control our genoa, I rigged the whisker pole, and at Mike’s suggestion we advanced “wing on wing.” Making 6 knots, we anticipated an overnight passage to Crete. Shipping was modest. Much of it we had left behind as many ships steered east through the Corinth Canal. Still, our AIS identified a large ship not far off our starboard bow. Soon thereafter it alarmed because another ship was overtaking us from behind. Our maneuvering room was slight given the oncoming ship. We waited to see whether our pursuer would alter course. When he did not, I hailed him on the VHF to add a voice to the small vessel he presumably had spotted from his bridge. “Do we have a problem?” I asked.

“No, no broblem,” came the accented reply, and we watched him veer slightly to port as he passed.

As we proceeded out of the Ionian and across the Hellenic Trench, Lisa pointed out landmarks—notably the “eyes of Venice” on the Peloponnesus where that great seafaring empire had built towers to survey all traffic heading up toward the Adriatic and “La Serenissima.” We passed Kithira, another place where Lisa had surveyed, but carried on under engine when the wind finally failed. By midday on June 7, we had passed the outcroppings of Crete and were approaching the old Venetian port of Chania.

We motored passed the submerged seawall that fails to protect the large outer harbor—a stormy anchorage—and passed the old lighthouse, over where the defensive chain once ran, and into the inner harbor. A spot in the heart of the tavern district and very near the Port Authority was open to us. We moored, and a friendly official provided us a map and directions to the Port Authority office. Again the drill: papers, insurance, crew list, transit log. An eyebrow might have been raised because we were missing an exit stamp from Pylos, but nothing was said and there was no mention of pollution insurance. The primary concern was agreement to pay the modest docking fee—with the transit log retained as guarantee.

Lisa had much to show us. The sight where she had helped preserve a Minoan structure threatened by a new street. The house she had almost purchased near the port. Her favorite restaurant with a heavenly sea urchin appetizer. The museum, curated by her friend, who welcomed her as a sister. And last, but far from least, Theodoris vice Demos—Chania’s foremost boat builder. To meet him, we walked along the marina past Venetian buildings being re-purposed as exhibit halls until we arrived at three long stone structures built to accommodate Venetian galleys under repair. The first had been converted into a café/sailing club. Another housed a striking replica of a Bronze Age galley constructed in 2004 and sailed/rowed from Chania to Athens for the Olympic Games. In between was the workshop of its builder—Theo.

One glance at the galley with rowing stations and oars for 20, and I was pretty sure my patience would be rewarded. I recovered Panope’s remaining oar quickly from the boat, and presented it to Theo. With Lisa interpreting, we quickly reached agreement. Yes, of course, it could be duplicated in a matter of a few days. My quest was over.

Edmund J. Hull was U.S. Ambassador to Yemen from 2001 to 2004, which culminated 30 years of diplomatic service in the Middle East and Washington. He is the author of High-Value Target: Countering Al Qaeda in Yemen, which was selected by the American Academy of Diplomacy as the most distinguished writing on American diplomacy in 2011.