The best way to avoid steering problems is to maintain the equipment. But you also need to have a Plan B if it does fail. (published March 2104)

Winds were brisk at 40 knots and the waves were large as we beam reached across the Southern Ocean on the Whitbread racer The Card. We were moving fast. “Drive it like you stole it!” was the axiom, when suddenly the wheel spun freely, lock to lock without doing anything to the course. Without hesitation, the driver stepped to the other side of the boat and gripped the leeward helm. He was again in control. But from the leeward wheel, he didn’t have a clear view of incoming waves or the telltales on the headsail that were dictating his actions. Someone jumped below to check the steering system.

Not every boat has two redundant steering systems. There are many types of steering systems and many types of failure. Tiller steering is probably the most direct and simplest, but seldom works very well on boats over 40 feet. I’ve used tiller steering on the Open Class 60 Thursday’s Child and while I generally liked the system, in difficult, broaching conditions it was hard to pull the tiller the critical last few inches in an attempted turn. Just when we needed that last few inches of rudder, they were sometimes impossible to get.

STEERING SYSTEMS

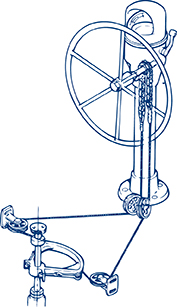

Many offshore cruising boats have single wheels with cable steering. The wheel is mounted on a pedestal. Inside the pedestal is a bicycle chain that travels over a center sprocket and the chain is connected to cables, which run through a series of sheaves down below. The cables connect to the steering quadrant that is fixed to the rudder post.

While it may sound complicated, in its most essential form, it’s pretty simple. The wheel should be able to rotate, lock to lock with the chain always in contact with the sprocket. If the cable starts to travel over the sprocket there may be a possibility of the chain and cable jumping off the sprocket, rendering the wheel ineffective. The chain should be flexible and lightly lubricated. The cables should run through all of the sheaves in the system, entering in line with each sheave and not chafing on the sides or “cheeks.” The idea is to minimize or eliminate friction and chafe.

Cables should be taut enough that they will not jump the sheave and get jammed between the sheave and cheek, but they should not be so taut that they cause unnecessary wear and load on the cable. Gear that is stowed anywhere near the steering system should be kept clear of all parts—cable, sheaves, and quadrant— in all conditions and angles of heel. Chafe, excessive loads, loose cables, misaligned chains or sheaves and extraneous equipment interfering with the steering system are all causes of steering failure over time. And whenever it happens, it won’t be convenient.

Redundant wheels may or may not solve the problem. Depending on the actual problem and the way the system is built and cables run, if one wheel ceases to steer the boat, the other wheel may or may not enable steering. If, for example, the cables exiting the pedestal are joined into one system at the base of the pedestal, the wheels may both rely upon one common set of cables to control the quadrant. If that set fails, neither wheel will function. Aboard The Card we had two completely independent sets of steering cables running from each wheel to the quadrant.

Cables aren’t the only means of controlling the quadrant. Solid rods are used in lieu of cables in some systems that push or pull the quadrant to control the rudder movement. There is a little less flexibility in how the system is run from the wheel to the quadrant, but there is also less slack in the system and therefore a better response at the wheel. Also, chafe is less of a problem.

Alternatively, hydraulic steering is popular on larger yachts and boats with center cockpits where running cables or solid rod steering is awkward or impractical. But hydraulics have their own set of problems because they rely on high pressure pumps and end fittings that can leak or fail. And, hydraulic steering does not give the helmsman any feel of the rudder.

There is always a long list of things to check prior to heading offshore, and when sailing with an hydraulic steering system, it is important to know that the system holds pressure and doesn’t leak. Plus, having replacement fluid and spare hoses aboard will allow you to make repairs should the system start to fail.

Ultimately, you need to have a backup plan. Any and all steering systems can fail. My first option when the steering fails is to turn on the autopilot. No autopilot? Then you need to get out the emergency tiller that will fit onto the rudder post and start hand steering. With the boat under control, you can focus on the real cause of the problem. It is prudent to carry spare cables and bulldog clamps. In a pinch, broken cables can be replaced with high-tensile line like Spectra, Dyneema or Vectran.

THE RUDDER IS GONE

In the worst case scenario where the rudder itself fails, you will have to jury rig a new steering system. Forget the idea of lashing the head door to the spinnaker pole to make a spare rudder; that’s a fairy tale that ends badly.

In the worst case scenario where the rudder itself fails, you will have to jury rig a new steering system. Forget the idea of lashing the head door to the spinnaker pole to make a spare rudder; that’s a fairy tale that ends badly.

Trimming your sails to sail the boat a particular direction will be tricky to say the least. Of course, sail trim will help with whatever solution you decide upon. Loads will be eased and your jury rig will perform better. In the meantime, you can heave to, slowing the boat to a crawl while you put your plan into effect.

In an emergency while singlehanding a monohull with tiller steering, I’ve used bungee cord to balance the tiller, then I over-trim the headsail and properly trim the main. When I leave the system alone, the boat alternately pinches into the wind and subsequently falls off again. The boat steers a zigzagged course, but the system allows me to eat or grab a few minutes of sleep.

Mike Birch, at one time the top offshore sailor in France, used a somewhat different method to temporarily control his 90-foot catamaran. He tied several buckets on each side deck of the boat. When he needed to steer to port, he dropped one or two buckets over the port side and the drag effectively steered the boat in that direction. It worked, but it wasn’t pretty.

Perhaps the best way to steer when the rudder fails is by using directionally controllable warps. I’ve used them in the Southern Ocean and one friend of mine used the same system to steer his sloop 1,000 miles to England when his rudder failed. In order to visualize the system, think of a heavy docking line that runs from one cockpit winch to the opposite winch in a big loop around the stern and outside of the backstay and everything else. In the middle of that line you have tied a loop in order to create a bridle.

From that loop in the middle of the bridle you tie several docking lines that trail behind the boat. The lines are your warps and if you want to reduce boat speed, you can tie overhand knots in them every few of feet.

With the original bridle on the winches, you can now adjust the position of the loop (and trailing warps) behind your boat by trimming the bridle from side to side. The directional force of the trailing warps will steer your boat and will slow it down in heavy weather conditions. I suggested this solution to one crew sailing from the East Coast to the Virgin Islands and, with 500 miles remaining in their journey, they were happy to find out how well it worked. It’s a system that takes about 20 minutes to create and doesn’t require any tools or equipment other than a few lines. It would be worth trying during a spring shakedown of your own boat.

We’re all easily lulled into complacency, but getting home safely requires vigilance and awareness. There can always be the rare and unforeseen events such as a collision with a container or rudder failure in big seas. You need to be prepared for those since your safety and the safety of those aboard may depend on it. Simple, regular inspections and maintenance of your steering system will help you to avoid most of the problems that can crop up. And learning to steer your boat without the rudder will get you home when things look dire. Problem avoidance is better than problem solving.

Bill Biewenga is a navigator, delivery skipper and weather router. His websites are www.weather4sailors.com and www.WxAdvantage.com. He can be contacted at billbiewenga@cox.net