Part I: The mighty Pacific Ocean shows its serene and tender disposition (published October 2013)

Having crossed the Atlantic via the “Milk Run” aboard our 1981 Dufour 35, my husband Markus and I felt we were ready for the “Coconut Milk Run” in the Pacific. Our son Nicky had crossed his first ocean at age four; now he was a “grown up” eight year old, the master of more useful knots and connoisseur of more constellations than the average suburban adult—or even the average weekend sailor. So he was ready, too, with a Lego collection that rivaled the depth and breadth of our toolbox and spare part reserves.

In some ways, a passage from Panama to the Galapagos resembles the typical opening leg for an Atlantic crossing from Gibraltar to the Canary Islands. After all, both trips cover 750 to 900 miles—about a week, give or take—and both are the prelude to a much larger venture on the order of 3,000 miles. But the similarities end there, a point we were acutely aware of on the eve of our departure from Panama.

That’s because the Canary Islands are a populated, well-connected outpost of Europe; the Galapagos, in contrast, are “only” an off-lying territory of Ecuador. For sailors on their way across the Atlantic, the run to the Canaries is often a shakedown cruise: just a week at sea, followed by the chance to reassess, re-provision and repair. The Canaries offer plenty of chandleries, boat yards, hardware stores and supermarkets. Crew or special equipment can easily be flown in. Problems that arise do not have to develop into full-fledged dramas, and anyone with cold feet can always sail back the way they came.

Not so with the Galapagos Islands. Jumping off from Panama to the Galapagos is the mental and physical equivalent of jumping off a much higher diving board into a much larger swimming pool. Galapagos-bound sailors cannot afford to learn things the hard way, because there’s no way out from there (short of extreme measures). Even when you arrive in the Galapagos, you’ve still only reached a tiny island outpost—a national park, at that, not a cruiser-friendly playground. There’s a lot of blue water west of the Galapagos, and whichever route you choose to follow—be it a 3,000 mile run to the Marquesas or 2,000 miles to Easter Island—will only bring you to a different, tiny island outpost, all the way to Tahiti, 3,650 miles as the booby flies. And even there it’s a long, long way to the next well-stocked port in New Zealand. And that is, after all, part of the appeal of crossing the Pacific.

Different ballpark, different ball game.

DIVING INTO THE PACIFIC

So there we stood, on the diving board of the Pacific, taking a very deep breath. Namani was laden down not only with food and water for this leg, but with as much as she could possibly carry for the months to follow. She didn’t so much sail away from Panama as waddle like an over-fed guest from a Thanksgiving feast. To make things more interesting still, we had our friend Bill onboard, who would give us not only good company but also the luxury of a three-person watch rotation for our maiden Pacific voyage. However, Bill absolutely had to be in Santa Cruz for the start of a non-refundable Galapagos tour, giving us a two-week window to make the 900-mile passage. Easy, right? We didn’t dare hope, knowing that any ocean-going venture is unpredictable.

Every passage has its defining challenge, be it weather, broken gear, or even crew harmony. We had read many reports of uncomfortable windward beats into contrary currents on this piece of ocean; other reports, meanwhile, were more focused on the problem of chafe over this sometimes windless, trans-equatorial passage. As we watched the skyscrapers of Panama City fade beyond the horizon, we wondered which challenge our voyage would bring.

Spill-over from the Caribbean trade winds in late February gave us a rip-roaring start, with the added thrill of a roller-coaster ride over the edge of the continent shelf. Here, 200-foot depths fall off into a 2,000-foot undersea precipice, a geography that manifests itself in lumpy surface waters. We were all glad when the bumps evened out 24 hours later, but not so glad to watch the winds flatten out with them. By the end of day three, we had broken into the threes: three degrees north latitude, and a meager three knots of speed made good in light air. By 6 p.m., we were chowing down on pasta and drifting along at a mere two knots—in the right direction, we thankfully noted. By midnight, Namani was going nowhere but rolling everywhere. More correctly, we were tracing circles: the quarter moon shone a teasing spotlight on our pathetic silhouette from all angles. First from starboard, then around the bow, and whoops, there it was to port. I was rapidly running out of synonyms for “lurch” as we rolled, floundered and tottered along in the vicinity of 03°45 N, 081°17W.

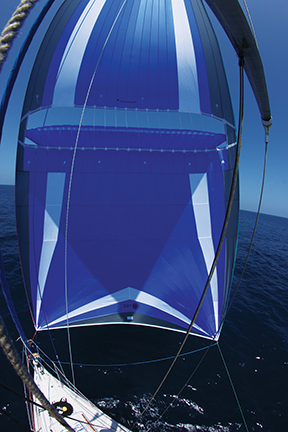

And it was only downhill from there, at least in terms of speed. Our 24-hour run over day three was a passable 108 miles; day two, a determined 94; and day five, a scanty 68 miles made good. It was high time to test whether our new Parasailor was worth the investment. This sail is a spinnaker-like, symmetric expanse of light fabric that works best slightly off the wind. Thanks to its cut-out “wing,” the Parasailor is much easier to set and maintain in light winds than a traditional spinnaker. Essentially, it’s a kite that flies itself, towing our docile sloop behind. All hands agreed that the wonder-sail also provided immediate relief for our rolling motion, thanks to the lifting force of the wing. Always in pursuit of the perfect noon sight, Markus took advantage of the stable platform to put our Astra sextant to use. The results, in fact, were satisfyingly close to our GPS position.

Delighted with our colorful new look and “speed,” it’s all relative when forward motion “jumps” from 2 to 3 knots, we set about another home improvement program: namely, a good scrub up for each of the crew. Having plenty of time and a relatively stable platform under us, we filled Nicky’s inflatable kiddie pool with salt water and each enjoyed a thorough soap-down in the cockpit, followed by a fresh water rinse. Luxury at its finest!

IN SEARCH OF WIND

The defining challenge for this passage had become apparent: speed, or lack thereof. Therefore, it was to be a test of patience more than endurance or fortitude. It seemed that we were destined to approach the Galapagos Islands at a ponderous, turtle-like pace. Appropriate, no? But what’s an unbearable curse to some is a blessing to others. Our passage became a leisurely, serene affair, exactly the antithesis to our anxious preparation period back in Panama. In fact, it turned out to be one of the most enjoyable passages we ever had. Even the rolling seas gradually eased to a very long, gentle swell. Mixing up a batch of muffins in the galley, an unthinkable proposition during our windward passage from the U.S. East Coast to the Bahamas, our motion was so mild that I had the fleeting sensation Namani was tethered in a marina somewhere.

The defining challenge for this passage had become apparent: speed, or lack thereof. Therefore, it was to be a test of patience more than endurance or fortitude. It seemed that we were destined to approach the Galapagos Islands at a ponderous, turtle-like pace. Appropriate, no? But what’s an unbearable curse to some is a blessing to others. Our passage became a leisurely, serene affair, exactly the antithesis to our anxious preparation period back in Panama. In fact, it turned out to be one of the most enjoyable passages we ever had. Even the rolling seas gradually eased to a very long, gentle swell. Mixing up a batch of muffins in the galley, an unthinkable proposition during our windward passage from the U.S. East Coast to the Bahamas, our motion was so mild that I had the fleeting sensation Namani was tethered in a marina somewhere.

Other than the occasional hour or two under engine for the thrill of a few miles made good, we slugged it out under sail. Why? One factor was budgetary because diesel isn’t cheap and would be even more expensive to replace in the Galapagos. Another was the lack of a better place to motor to: we found no point in reaching another blank place on the chart that was equally devoid of wind.

Meanwhile, Namani was still on track to make Bill’s deadline, even at her sluggish two to three knot pace—thanks to our quick shot out of the starting blocks and the occasional, ambitious puff of wind that treated us to a brief but exhilarating four knot gallop. One reason we left home and jobs behind to go cruising was to escape the harrying clock that had so defined every aspect of our former lives. Instead of scrutinizing the time, we clung to reports on the behavior of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, the force with its finger on the wind controls. Since the ITCZ was weakly defined at that point in time, more of the same light conditions were expected.

Things were going swimmingly just as they were. So much so that we made a swim call, taking turns to go for an exhilarating dip in 9,000-foot depths. After Nicky suffered the only injury of the trip in the form of a jellyfish sting, we launched our inflatable kayak for a quick paddle around Namani on the boundless, silvery blue sea. It was an eerie feeling to be even a few yards away from the mother ship, although seas were calm and visibility perfect. I wondered if the crews of early exploratory missions felt the same pang when setting out into oceans that must have seemed even vaster than they do today. Like them, we scanned our watery world from the mast top and found nothing. Or rather, a fascinating, fluid landscape painting in which the hills shifted, rose and approached before shuffling toward the opposite horizon.

LAND HO!

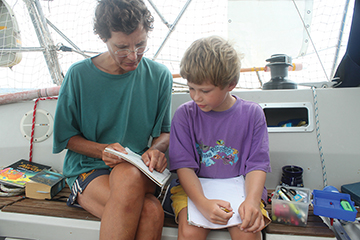

By day six, we could begin to hazard a guess as to our arrival date: three more days. Slow, but still on target. By that point, we had thoroughly given ourselves over to the “Que sera, sera” approach to ocean sailing, anyway. Conditions were ideal for cetacean spotting, and we glimpsed a lone orca followed by two pods of striped dolphins. They seemed a little disappointed in our pedestrian speed, however, and raced off to find less geriatric playmates. Then it was time to make a dent in Nicky’s home schooling and stitch together a flag of Ecuador. The moon was nearly full now, stealing the celestial stage from the stars but bringing us a welcome visitor every night. I was gradually wading through a 700-page book on the building of the Panama Canal, a process that mirrored our journey, though the pages seemed to turn slowly, my bookmark made steady progress toward the end. As if on cue, birds began to appear around us signaling that land couldn’t be too far off.

Namani was rapidly approaching the equator and we had a party to plan for day nine. Having never crossed that milestone by sea before, we were all pollywogs. Therefore, we assigned the role of Neptune to Nicky’s stuffed animal, a monkey named Frodo who was “born” in Indonesia and had therefore presumably crossed the Equator at some point. Frodo made a solemn Neptune who presided over the pollywog trials, accusing each of us of dastardly crimes. Those were formulated in secrecy the previous night, each crew member writing one accusation for each of his crewmates: heinous misdeeds along the lines of leaving Legos for the barefoot night watchman to find the hard way. During the trials and subsequent punishment, Nicky got a little carried away in smearing the guilty parties (including himself) with shaving cream, and all of us sported silly headgear. Finally, each crewmember dutifully sacrificed a piece of his or her celebratory brownie to Neptune. From then on, we could call ourselves shellbacks and note our latitude in degrees south, a rewarding feeling to say the least.

Dawn on day ten brought the sight of Cristobal’s sloping, crater-poked form: our first Pacific landfall. The only hiccup of a passage full of impressions (if not dramatic events) came when we turned the key to the ignition and listened to the engine sputter, then die. Having patiently waited all these days, we were suddenly itching to get in to port—preferably before the rapidly approaching Friday 5 p.m. mark in order to clear in. The clock, a lesser member of our passagemaking cast until now, immediately took center stage with its loud ticking. Just as Markus cleared up a clogged fuel line, the wind came back in a rush, ushering Namani briskly into Wreck Bay. On the way in, we were treated to a final ocean spectacle. A patch of boiling water stirred up by an agitated school of fish, preyed upon by leaping dolphins and swooping frigate birds that delicately plucked snacks out of the sea. We had “made it” on all counts, not just into port, but with enough time to clear customs and a full two days to spare before Bill’s tour began.

This passage showed us the ocean at its most serene. The Pacific, it seems, could really live up to its name. We grew to appreciate the value of a slow, even, and easy passage—950 miles in ten days, which is our pick every time over a fast, uncomfortable one, especially as a cruising family out to savor our time together in special places.

And savor it we did, for the duration of the passage and over the next three weeks in the magical Galapagos Islands. Then it would be time to take the next deep breath and set sail for the big one: 3,000 miles to the Marquesas.

Nadine Slavinski is the author of the book Lesson Plans Ahoy: Hands-On Learning for Sailing Children and Home Schooling Sailors. Currently on sabbatical from teaching, she cruises aboard her 35-foot sloop, Namani, with her husband and young son. They are currently in New Zealand and looking forward to new Pacific landfalls. Her website, www.sailkidsed.net lists free resources for home schooling sailors.